Will This Artificial Womb One Day Improve the Care of Preemies?

A new treatment, tested on lambs, involves letting fetuses mature in fluid-filled sacs

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f8/47/f847453d-7144-4ed2-a3ca-6876bd51dcb1/baby.jpg)

In the 1870s, French obstetrician Stéphane Tarnier, inspired by a trip to the chicken incubator display at the Paris Zoo, invented the first incubator for premature babies. This primitive incubator, which was warmed by a hot water bottle, reduced infant mortality by 50 percent.

Tarnier’s invention was the first in a series of technologies designed to help the youngest, smallest babies survive. Since about 1 in 10 babies globally is born premature, this has been a major medical priority for the past 150 years. Today, our technology has grown so advanced that more than half of babies born at 24 weeks—a little over halfway through a normal 40-week pregnancy—survive. But many do so with disabilities, including blindness, lung damage or cerebral palsy, and most babies born even earlier will die shortly after birth.

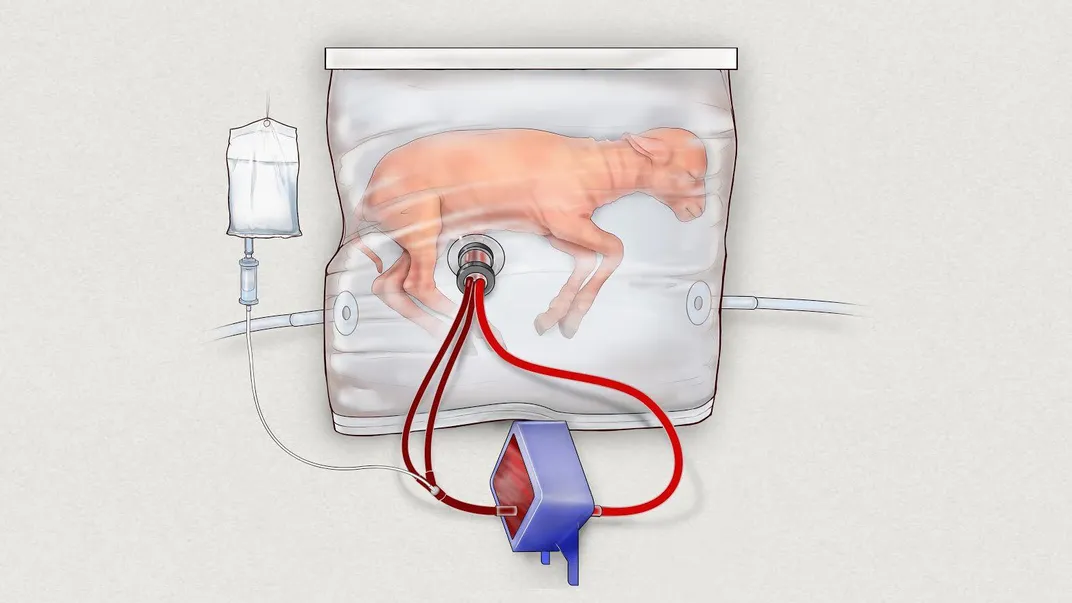

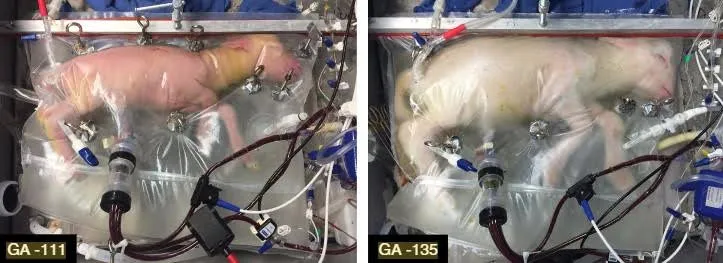

Now, researchers have developed a technology that may eventually make it possible for even the tiniest preemies to live—and live without major health consequences. It’s a fluid-filled extra-uterine support device—basically, an artificial womb. They’ve tested it on fetal lambs, who have seemed to thrive, and applied for a patent.

"[Extremely premature] infants have an urgent need for a bridge between the mother's womb and the outside world," said Alan W. Flake, who led the research, in a statement. "If we can develop an extra-uterine system to support growth and organ maturation for only a few weeks, we can dramatically improve outcomes for extremely premature babies."

Flake is a fetal surgeon and the director for the Center for Fetal Research at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). His team’s research was reported last week in the journal Nature Communications.

The system is a container, which looks more or less like a plastic bag, filled with temperature-controlled, sterile, artificial amniotic fluid. The fetuses breathe this fluid, as their lungs are not yet developed to thrive on air or oxygen. The blood from their umbilical cords goes into a gas exchange machine that serves as the placenta, where it’s oxygenated and returned. The system doesn’t use an external pump for circulation, as research has shown that even the gentlest of artificial pressure can harm a tiny heart, so all pressure is generated by the fetus’s own heart.

This is, needless to say, extremely different than the current standard of care for premature babies. “[Currently] these babies are delivered to the outside world, they are ventilated with gas, which arrests lung development, they’re exposed to infectious pathogens,” said Flake, in a press briefing. “The basic cause of their problems is they have very immature organs, they’re simply not ready to be delivered, and also the therapy we employ can be damaging.”

The artificial womb system is intended for babies between 23 and 28 weeks of gestation; after 28 weeks, babies are generally strong enough to survive in traditional incubators.

The experiment, which was conducted with six lambs born at the equivalent of 23 or 24 weeks gestation, worked for up to 28 days with some of the animals. The lambs got larger, grew wool and showed normal activity, brain function and organ development. Some lambs that spent time in the artificial wombs are now as old as a year, and seem perfectly normal, according to researchers.

The next step will be to further improve the system, and figure out how to make it small enough for human babies, who are a third the size of the lambs. The researchers believe these artificial wombs might be ready for human use in a decade or so. If so, they could potentially reduce the number of deaths and disabilities, as well as save some of the $43 billion spent on medical care for preemies annually in the United States.

Unsurprisingly, the work is not without controversy and ethical implications. Would testing the device on human babies, when early iterations are so likely to fail, be cruel? Some bioethicists worry artificial wombs could lead to a situation where women are forced by insurance companies to use them to avoid costly pregnancy and delivery complications. Or that employers could pressure women to use the systems instead of taking maternity leave. Some journalists and members of the public simply seem squeamish about the idea of using technology in what’s seen to be a “natural” process. Articles about the technology over the past week inevitably seem to mention dystopian sci-fi, like Brave New World and Gattaca. A Facebook acquaintance of mine posted an article about the technology to his page, commenting in all caps: TERRIFYING.

Then, of course, there are bioethicists and others who speculate whether such a device could mean the end of biological pregnancy entirely. Surely, some would welcome this—some women are born without uteruses, or lose them due to disease, but would still like to carry a pregnancy. This has led to the development of uterine transplantation, but the procedure is still risky; the first uterine transplant in America, done last year at the Cleveland Clinic, failed after a few weeks, resulting in the organ’s removal. Other women do have uteruses but cannot, for one reason or another, carry a pregnancy. Then there are those who would rather not be pregnant for social or emotional reasons—the radical 1970s feminist Shulamith Firestone argued that pregnancy was inherently oppressive, and that artificial uteruses were necessary for women to be truly liberated.

The researchers say their system will not replace pregnancy, nor do they think such a technology is possible, at least anytime in the foreseeable future. They don’t even intend the device to push the limits of viability beyond the current 23 or so weeks. They say the only purpose of the technology is to help viable babies survive and grow without disability.

To us, this seems like science fiction. To Stéphane Tarnier, the 19th century incubator innovator, it probably would have seemed like magic.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)