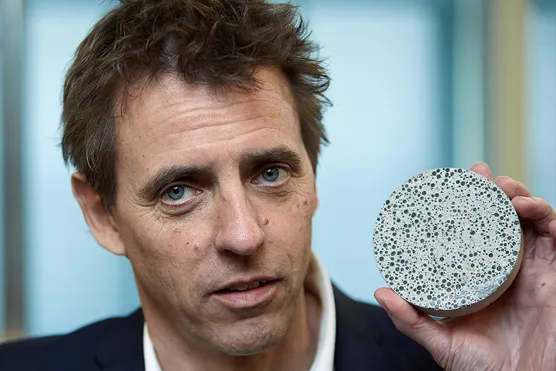

With This Self-Healing Concrete, Buildings Repair Themselves

A concrete developed by Dutch scientists and embedded with limestone-producing bacteria is ready to hit the market

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/30/65302b94-3cbc-43ab-ad97-21e331fbaac5/jonkers-concrete.jpg)

When you break your leg, it eventually knits itself back together. Osteoblast cells produce minerals that create the structure of new bone, turning fragments back into a whole.

Why, thought microbiologist Henk Jonkers, can’t buildings do the same thing?

Inspired by the human body, Jonkers, who works at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, created self-healing concrete. He embeds the concrete with capsules of limestone-producing bacteria, either Bacillus pseudofirmus or Sporosarcina pasteurii, along with calcium lactate. When the concrete cracks, air and moisture trigger the bacteria to begin munching on the calcium lactate. They convert the calcium lactate to calcite, an ingredient in limestone, thus sealing off the cracks.

This innovation could solve a longstanding problem with concrete, the world’s most common construction material. Concrete often develops micro-cracks during the construction process, explains Jonkers. These tiny cracks don’t immediately affect the building’s structural integrity, but they can lead to leakage problems. Leakage can eventually corrode the concrete’s steel reinforcements, which can ultimately cause a collapse. With the self-healing technology, cracks can be sealed immediately, staving off future leakage and pricey damage down the road. The bacteria can lie dormant for as long as 200 years, well beyond the lifespan of most modern buildings.

Jonkers has been road-testing the self-healing concrete on a lifeguard station, which is by nature prone to wind and water damage. The structure has remained watertight since 2011, he says. The invention has also recently earned Jonkers a nomination for a European Inventors Award, with winners being announced at a June 11 ceremony in Paris.

This year, the technology will hit the market for the first time. It will come as three separate products: self-healing concrete, a repair mortar and a liquid repair medium. Unfortunately, the costs of the technology are still quite high, about €30-40 (about $33-44) per square meter. This means it will initially only be viable for projects where leakage and corrosion are particularly problematic, such as underground and underwater structures. The price of the calcium lactate needed for the bacteria to produce calcite is part of the problem, but Jonkers and his team are working to create a cheaper, sugar-based alternative. And as demand for the concrete increases, the price should decrease.

“We are currently in the process of upscaling its production,” says Jonkers. “Our expectation is that we can deliver the healing agent in large quantities [by the] middle of 2016.”

Other types of self-repairing concrete are under development around the world. In the UK, researchers at the University of Bath, Cardiff University and Cambridge have developed a material similar to Jonkers' that uses bacteria to fill in crevices, which they hope could be used to repair roads and other infrastructure. They estimate it could reduce costs by up to 50 percent. MIT scientists have been working on a concrete healing system that uses sunlight to activate polymer microcapsules, which would plug cracks. A University of Michigan engineer has come up with a concrete with microfibers that bends instead of breaking; if tiny tears do occur, the material expands and reinforces itself with calcium carbonate.

Victor Li, the University of Michigan engineer, says the advantage of products like his is that they can actually recover the original load-bearing capacity of the concrete rather than simply filling in the gaps with healing products.

"I expect self-healing concrete to be in use within the next few years," he says.

Concrete production accounts for a massive 5 percent of the world’s carbon emissions, and global demand for concrete has doubled over the past decade, largely due to increasing urbanization. So any technology that makes concrete structures longer lasting has the potential not just to cut costs but to reduce our carbon footprint. The future of green building, it seems, may be gray.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)