The World’s First Exhibition on Yoga in Art (Photos)

“Yoga: The Art of Transformation” opens at the Sackler Gallery

Image and caption courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery India, Karnataka, Mysore, 13th century; Chloritic schist, 116.6 x 49.23 cm

The Cleveland Museum of Art: John L. Severance Fund

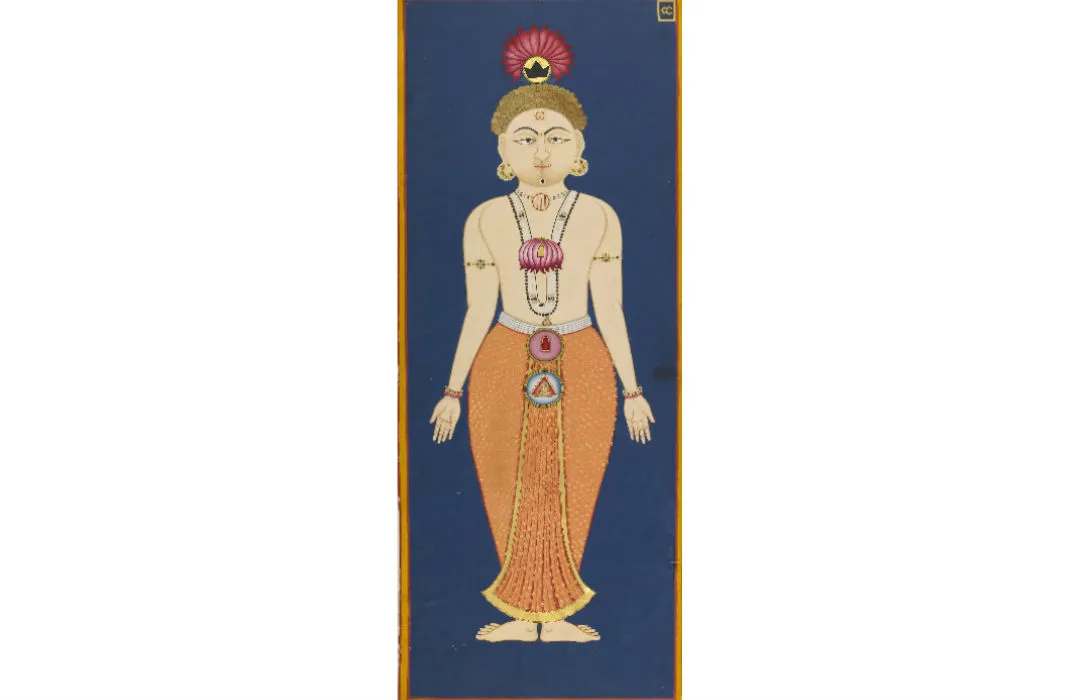

Image and caption courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Folio 4 from the Siddha Siddhanta Paddhati by Bulaki

India, Rajasthan, Jodhpur, dated 1824; Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 122 x 46 cm

Mehrangarh Museum Trust

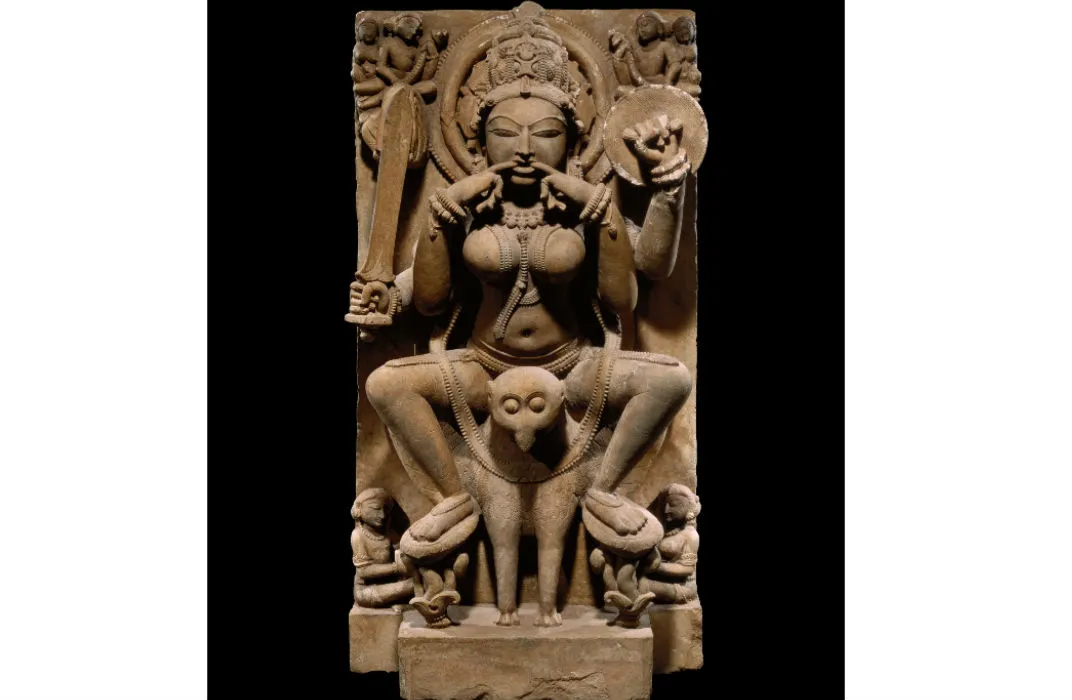

Image and caption courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery India, Uttar Pradesh, Kannauj, ca. 1000-1050 CE; Sandstone, 86.4 x 43.8 x 24.8 cm

San Antonio Museum of Art, purchased with the John and Karen McFarlin Fund and Asian Art Challenge Fund

Image and caption courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery India, Tamil Nadu, Kanchipuram, ca. 900-975; Metagabbro, H x W x D: 116 x 76 x 43.2 cm

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Gift of Arthur M. Sackler

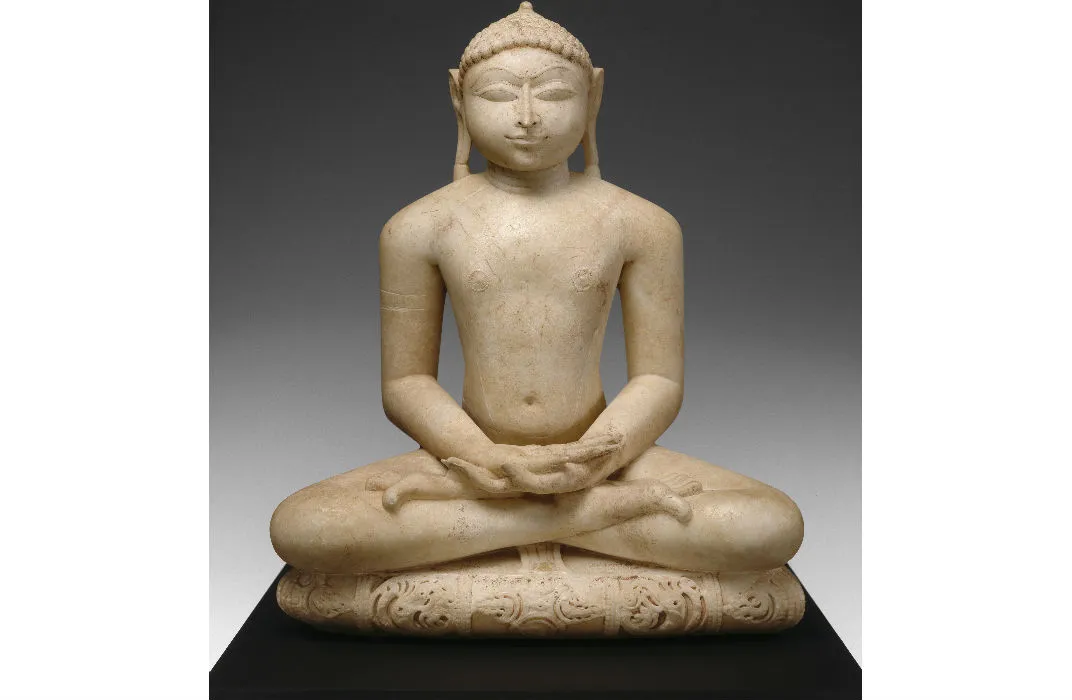

Image and caption courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery India, Rajasthan, probably vicinity of Mount Abu, dated 1160; Marble, 59.69 x 48.26 x 21.59 cm

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, The Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund

Image and caption courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery India, Rajasthan, Jaipur, ca. 1800-20; Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 38.5 x 28cm

Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Given by Mrs. Gerald Clark

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Satcakranirupanicitra-Yoga-Freer-Sackler-963.jpg)

Image and caption courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Swami Hamsvarupa; Trikutvilas Press, Muzaffarpur, Bihar, India, 1903

Book, 26.2 × 34.5 × 0.4 cm

Wellcome Library, London, Asian Collections

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Bulaki-Yoga-Freer-Sackler-963.jpg)

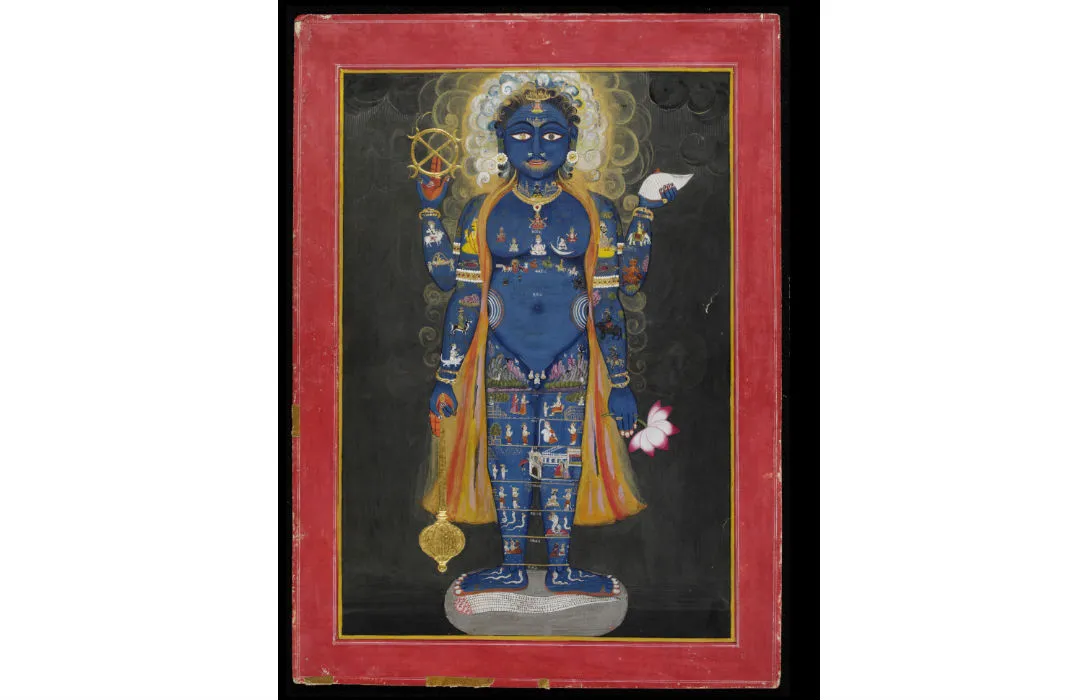

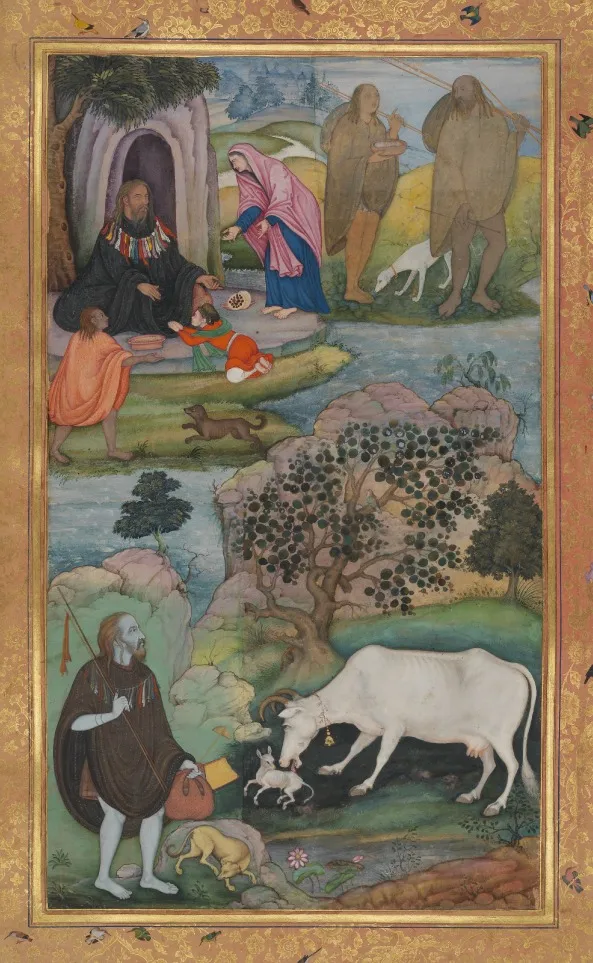

Image and caption courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Folio 1 from the Nath Charit by Bulaki; India, Rajasthan, Jodhpur, 1823 (Samvat 1880)

Opaque watercolor, gold and tin alloy on paper, 47 x 123 cm

Mehrangarh Museum Trust

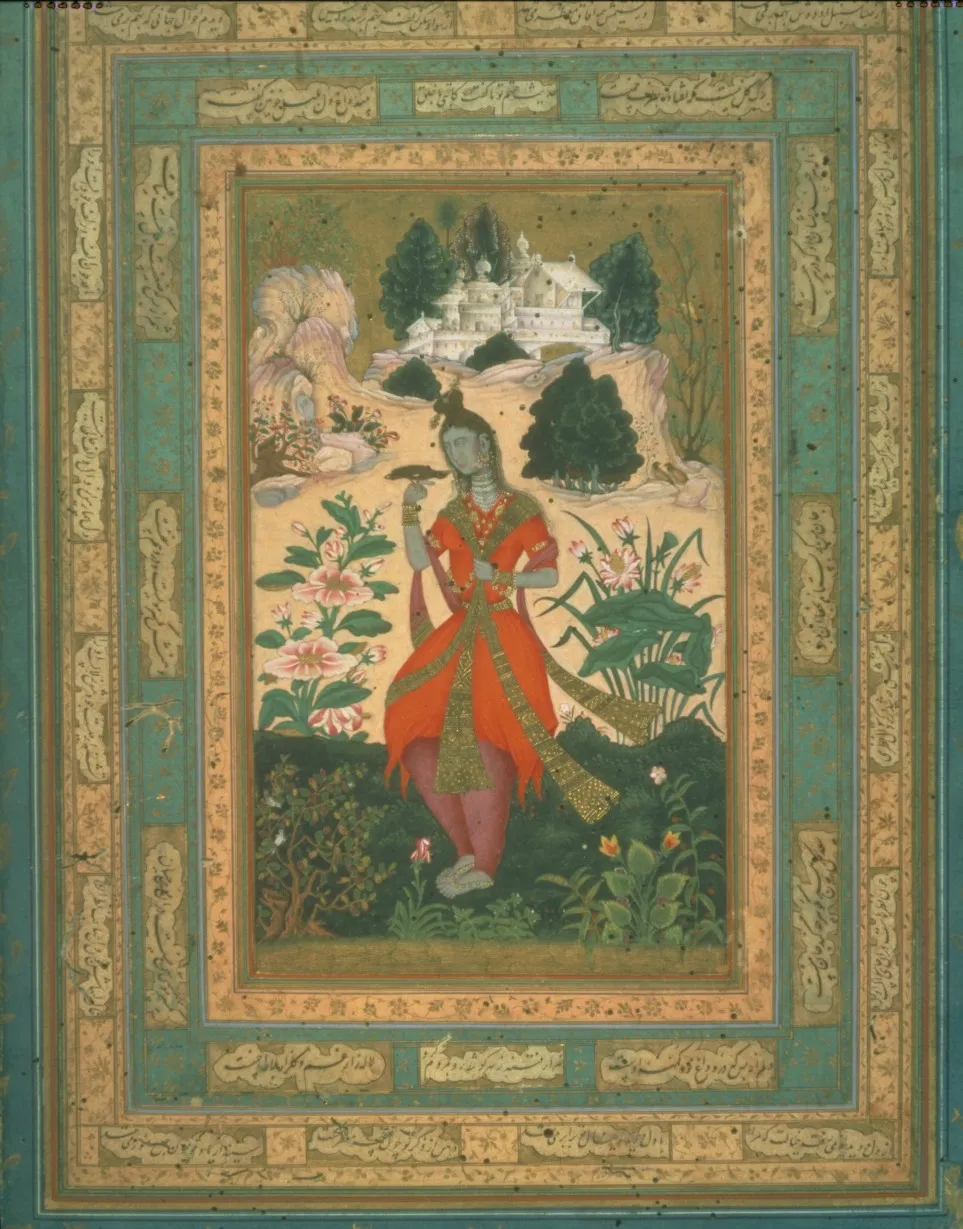

Image and caption courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery By the Dublin painter; India, Karnataka, Bijapur, ca. 1603-4

Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 42 x 32 cm

Chester Beatty Library

Opaque watercolor on paper, 22.2 x 13.9 cm

Chester Beatty Library

Image and caption courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Western India, dated 1333; Bronze, 21.9 x 13.1 x 8.9 cm

Freer Gallery of Art

Image and caption courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery India, Mughal dynasty, ca. 1600-1625; Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 53.5 x 40 cm

Staatsbibliothek zu Berline – Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Orientabteilung

Image and caption courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery India, Mughal dynasty, ca. 1600-1625; Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 53.5 x 40 cm

Staatsbibliothek zu Berline – Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Orientabteilung

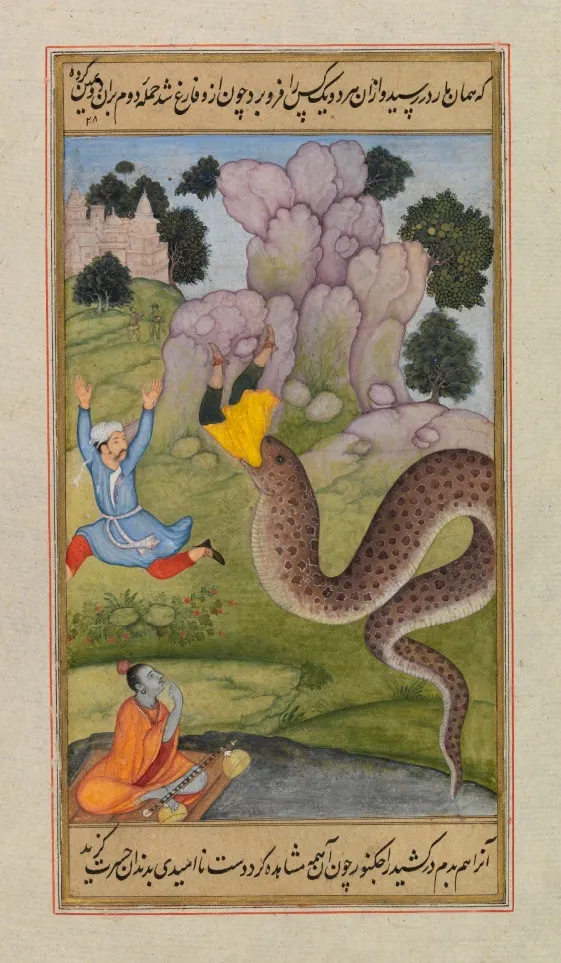

Image and caption courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery From The Magic Doe Woman (Mrigavati), attributed to Haribans, 1603-4

Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 28.3 x 17 cm

Chester Beatty Library, Credit Line

Image and caption courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery From the Akbarnama, composed by Basawan and painted by Asi

India, Mughal dynasty, ca. 1590-5; Opaque watercolor, gold and ink on paper, 38.1 x 22.4 cm

Victoria and Albert Museum

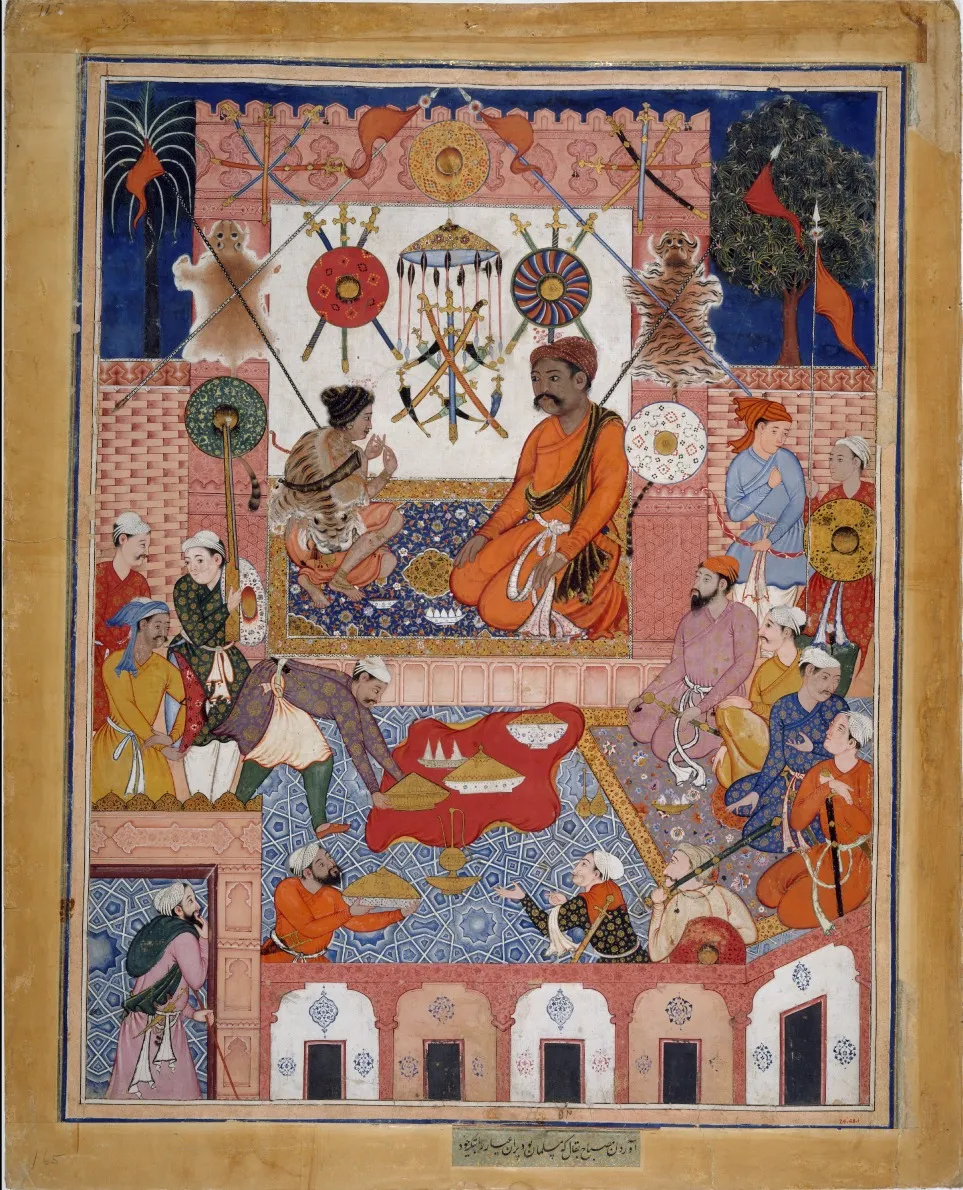

Image and caption courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Folio from a Hamzanama (The Adventures of Hamza)

Attributed to Dasavanta and Mithra, ca. 1570

Opaque watercolor, gold and ink on cotton 67.5 x 52.2 cm, 70.8 x 54.9 cm (folio)

Image and caption courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery India, Jammu and Kashmir, Harwan, 5th century; Terracotta, 40.6 × 33.6 × 4.1 cm

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Cynthia Hazen Polsky

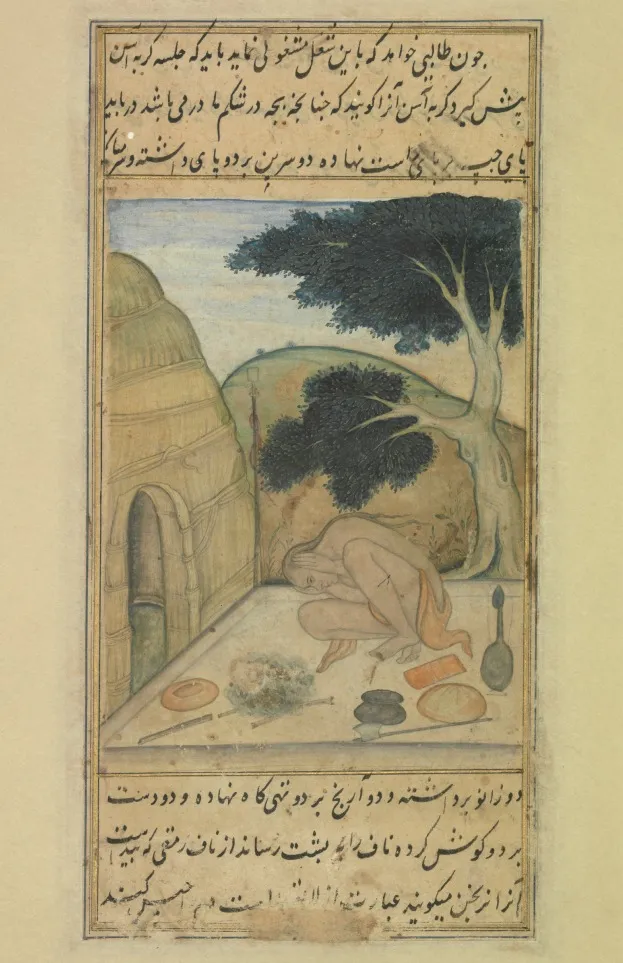

In the 17th-century watercolor painting pictured above and featured in "Yoga: The Art of Transformation," an upcoming exhibition at the Sackler Gallery, a man sits on a mat outside a hut, contorted into a fetal position. The picture is one of the exhibit’s 10 folios from the Bahr al-Hayat, the earliest known treatise to illustrate yoga postures systematically.

Today, yoga is practiced by millions, in styles that range from tranquil relaxation poses to intense workouts. But the activity emerged centuries before stretchy yoga pants were invented. Indian spiritual leaders conceived it a means of disciplining the body and mind as early as 500 BCE, and over time Hindu, Buddhist and Jain schools philosophically ordered the practice into its various forms.

"Yoga: The Art of Transformation," the world’s first yogic art exhibition, visually traces yoga’s development and dissemination. In addition to the 10 Bahr al-Hayat folios, which have never been shown in the United States before, the exhibition includes more than 100 temple sculptures, devotional icons, illustrated manuscripts, court paintings, photographs, books and films borrowed from 25 museums and private collections in India, Europe and the United States.

"These works of art allow us to trace, often for the first time, yoga’s meanings across the diverse social landscapes of India," said Debra Diamond, the museum’s curator of South Asian art. "United for the first time, they not only invite aesthetic wonder, but also unlock the past—opening a portal onto yoga’s surprisingly down-to-earth aspects over 2,000 years."

The exhibition opens on October 19 and runs through January 26 next year.

Image courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.