Hamilton Takes Command

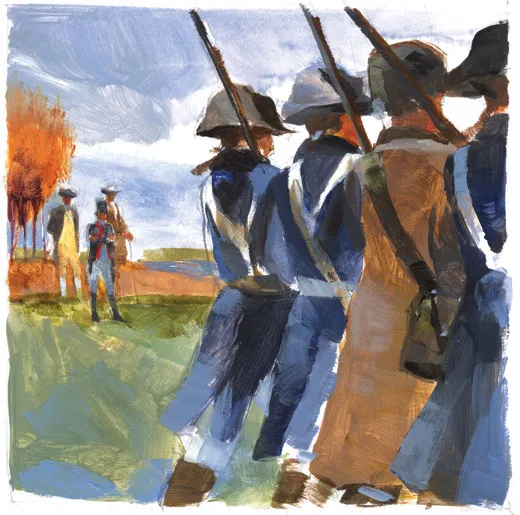

In 1775, the 20-year-old Alexander Hamilton took up arms to fight the British

“ALEXANDER HAMILTON is the least appreciated of the founding fathers because he never became president,” says Willard Sterne Randall, a professor of humanities at ChamplainCollege in Burlington, Vermont, and the author of Alexander Hamilton: A Life, released this month from HarperCollins Publishers. “Washington set the mold for the presidency, but the institution wouldn’t have survived without Hamilton.”

Hamilton was born January 11, 1755, on the island of Nevis in the West Indies, the illegitimate son of James Hamilton, a merchant from Scotland, and Rachel Fawcett Levine, a doctor’s daughter who was divorced from a plantation owner. His unmarried parents separated when Hamilton was 9, and he went to live with his mother, who taught him French and Hebrew and how to keep the accounts in a small dry goods shop by which she supported herself and Hamilton’s older brother, James. She died of yellow fever when Alexander was 13.

After her death, Hamilton worked as a clerk in the Christiansted (St. Croix) office of a New York-based import-export house. His employer was Nicholas Cruger, the 25-year-old scion of one of colonial America’s leading mercantile families, whose confidence he quickly gained. And in the Rev. Hugh Knox, the minister of Christiansted’s first Presbyterian church, Hamilton found another patron. Knox, along with the Cruger family, arranged a scholarship to send Hamilton to the United States for his education. At age 17, he arrived in Boston in October 1772 and was soon boarding at the ElizabethtownAcademy in New Jersey, where he excelled in English composition, Greek and Latin, completing three years’ study in one. Rejected by Princeton because the college refused to go along with his demand for accelerated study, Hamilton went instead in 1773 to King’s College (now ColumbiaUniversity), then located in Lower Manhattan. In events leading up to the excerpt that follows, Hamilton was swept up by revolutionary fervor and, at age 20, dropped out of King’s College and formed his own militia unit of about 25 young men.

In June 1775, the Continental Congress in Philadelphia chose Virginia delegate Col. George Washington as commander in chief of the Continental Army then surrounding British-occupied Boston. Hurrying north, Washington spent a day in New York City, where, on Sunday, June 25, 1775, Alexander Hamilton braced at attention for Washington to inspect his militiamen at the foot of Wall Street.

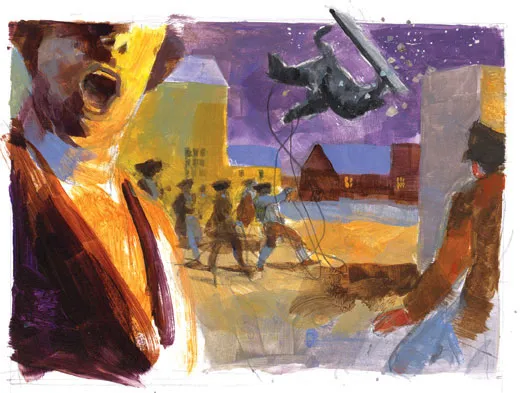

Two months later, the last hundred British troops withdrew from Manhattan, going aboard the 64-gun man-of-war Asia . At 11 o’clock on the night of August 23, Continental Army Artillery captain John Lamb gave orders for his company, supported by Hamilton’s volunteers and a light infantry unit, to seize two dozen cannons from the battery at the island’s southern tip. The Asia’s captain, having been warned by Loyalists that the Patriots would raid the fort that night, posted a patrol barge with redcoats just offshore. Shortly after midnight, the British spotted Hamilton, his friend Hercules Mulligan, and about 100 comrades tugging on ropes they had attached to the heavy guns. The redcoats opened a brisk musket fire from the barge. Hamilton and the militiamen returned fire, killing a redcoat. At this, the Asiahoisted sail and began working in close to shore, firing a 32-gun broadside of solid shot. One cannonball pierced the roof of FrauncesTavern at Broad and Pearl Streets. Many years later Mulligan would recall: “I was engaged in hauling off one of the cannons, when Mister Hamilton came up and gave me his musket to hold and he took hold of the rope. . . . Hamilton [got] away with the cannon. I left his musket in the Battery and retreated. As he was returning, I met him and he asked for his piece. I told him where I had left it and he went for it, notwithstanding the firing continued, with as much concern as if the [Asia] had not been there.”

Hamilton ’s cool under fire inspired the men around him: they got away with 21 of the battery’s 24 guns, dragged them uptown to CityHallPark and drew them up around the Liberty Pole under guard for safekeeping.

On January 6, 1776, the New York Provincial Congress ordered that an artillery company be raised to defend the colony; Hamilton, unfazed that virtually all commissions were going to native colonists of wealth and social position, leaped at the opportunity. Working behind the scenes to advance his candidacy, he won the support of Continental Congressmen John Jay and William Livingston. His mathematics teacher at King’s College vouched for his mastery of the necessary trigonometry, and Capt. Stephen Bedlam, a skilled artillerist, certified that he had “examined Alexander Hamilton and judges him qualified.”

While Hamilton waited to hear about his commission, Elias Boudinot, a leader of the New Jersey Provincial Congress, wrote from Elizabethtown to offer him a post as brigade major and aide-de-camp to Lord Stirling (William Alexander), commander of the newly formed New Jersey Militia. It was tempting. Hamilton had met the wealthy Scotsman as a student at ElizabethtownAcademy and thought highly of him. And if he accepted, Hamilton would likely be the youngest major in the Revolutionary armies. Then Nathanael Greene, a major general in the Continental Army, invited Hamilton to become his aide-de-camp as well. After thinking the offers over, Hamilton declined both of them, gambling instead on commanding his own troops in combat.

Sure enough, on March 14, 1776, the New York Provincial Congress ordered Alexander Hamilton “appointed Captain of the Provincial Company of Artillery of this colony.” With the last of his St. Croix scholarship money, he had his friend Mulligan, who owned a tailor shop, make him a blue coat with buff cuffs and white buckskin breeches.

He then set about recruiting the 30 men required for his company. “We engaged 25 men [the first afternoon],” Mulligan remembered, even though, as Hamilton complained in a letter to the provincial congress, he could not match the pay offered by Continental Army recruiters. On April 2, 1776, two weeks after Hamilton received his commission, the provincial congress ordered him and his fledgling company to relieve Brig. Gen. Alexander McDougall’s First New York Regiment, guarding the colony’s official records, which were being shipped by wagon from New York’s City Hall to the abandoned Greenwich Village estate of Loyalist William Bayard.

In late May 1776, ten weeks after becoming an officer, Hamilton wrote to New York’s provincial congress to contrast his own meager payroll with the pay rates spelled out by the Continental Congress: “You will discover a considerable difference,” he said. “My own pay will remain the same as it is now, but I make this application on behalf of the company, as I am fully convinced such a disadvantageous distinction will have a very pernicious effect on the minds and behavior of the men. They do the same duty with the other companies and think themselves entitled to the same pay.”

The day the provincial congress received Captain Hamilton’s missive, it capitulated to all his requests. Within three weeks, the young officer’s company was up to 69 men, more than double the required number.

Meanwhile, in the city, two huge bivouacs crammed with tents, shacks, wagons and mounds of supplies were taking shape. At one of them, at the juncture of present-day Canal and Mulberry Streets, Hamilton and his company dug in. They had been assigned to construct a major portion of the earthworks that reached halfway across ManhattanIsland. Atop Bayard’s Hill, on the highest ground overlooking the city, Hamilton built a heptagonal fort, Bunker Hill. His friend Nicholas Fish described it as “a fortification superior in strength to any my imagination could ever have conceived.” When Washington inspected the works, with its eight 9-pounders, four 3-pounders and six cohorn mortars, in mid-April, he commended Hamilton and his troops “for their masterly manner of executing the work.”

Hamilton also ordered his men to rip apart fences and cut down some of the city’s famous stately elm trees to build barricades and provide firewood for cooking. In houses abandoned by Loyalists, his soldiers propped muddy boots on damask furniture, ripped up parquet floors to fuel fireplaces, tossed garbage out windows and grazed their horses in gardens and orchards. One Loyalist watched in horror as army woodcutters, ignoring his protests, chopped down his peach and apple orchards on 23rd Street . Despite a curfew, drunken soldiers caroused with prostitutes in the streets around TrinityChurch. By midsummer, 10,000 American troops had transformed New York City into an armed camp.

The very day—July 4, 1776—that the founding fathers of the young nation-to-be were signing the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia, Captain Hamilton watched through his telescope atop Bayard’s Hill as a forest of ship masts grew ominously to the east; in all, some 480 British warships would sail into New York Harbor. One of Washington’s soldiers wrote in his diary that it seemed “all London was afloat.” Soon they had begun to disgorge the first of what would swell to 39,000 troops—the largest expeditionary force in English history—onto Staten Island. On July 9, at 6 o’clock in the evening, Hamilton and his men stood to attention on the commons to hear the declaration read aloud from the balcony of City Hall. Then the soldiers roared down Broadway to pull down and smash the only equestrian statue of King George III in America.

Three days later, British Vice Admiral Lord Richard Howe detached two vessels from his flotilla, the 44-gun Phoenixand the 28-gun Rose, to sail up the Hudson and probe shore defenses. The captain of the Rose coolly sipped claret on his quarterdeck as his vessel glided past the battery on Lower Manhattan—where an ill-trained American gun crew immediately blew itself up. The ships sailed unmolested up the river to Tarrytown as colonial troops abandoned their posts to watch. An appalled Washington fumed: “Such unsoldierly conduct gives the enemy a mean opinion of the army.” On their return, the two British ships passed within cannon range of Hamilton’s company at FortBunker Hill. He ordered his 9-pounders to fire, which the British warships returned. In the brief skirmish, one of Hamilton’s cannons burst, killing one man and severely wounding another.

On August 8, Hamilton tore open orders from Washington: his company was to be on round-the-clock alert against an imminent invasion of Manhattan. “The movements of the enemy and intelligence by deserters give the utmost reason to believe that the great struggle in which we are contending for everything dear to us and our posterity, is near at hand,” Washington wrote.

But early on the morning of August 27, 1776, Hamilton watched, helpless, as the British ferried 22,000 troops from Staten Island, not to Manhattan at all, but to the village of Brooklyn, on Long Island. Marching quickly inland from a British beachhead that stretched from Flatbush to Gravesend, they met little resistance. Of the 10,000 American troops on Long Island, only 2,750 were in Brooklyn, in four makeshift forts spread over four miles. At Flatbush, on the American east flank, Lord Charles Cornwallis quickly captured a mounted patrol of five young militia officers, including Hamilton’s college roommate, Robert Troup, enabling 10,000 redcoats to march stealthily behind the Americans. Cut off by an 80-yard-wide swamp, 312 Americans died in the ensuing rout; another 1,100 were wounded or captured. By rowboat, barge, sloop, skiff and canoe in a howling northeaster, a regiment of New England fishermen transported the survivors across the East River to Manhattan.

At a September 12, 1776, council of war, a grim-faced Washington asked his generals if he should abandon New York City to the enemy. Rhode Islander Nathanael Greene, Washington’s second-in-command, argued that “a general and speedy retreat is absolutely necessary” and insisted, as well, that “I would burn the city and suburbs,” which, he maintained, belonged largely to Loyalists.

But Washington decided to leave the city unharmed when he decamped. Before he could do so, however, the British attacked again, at Kip’s Bay on the East River between present- day 30th and 34th Streets, two miles north of Hamilton’s hill fort, leaving his company cut off and in danger of capture. Washington sent Gen. Israel Putnam and his aide-decamp, Maj. Aaron Burr, to evacuate them. The pair reached Fort Bunker Hill just as American militia from Lower Manhattan began to stream past Hamilton heading north on the Post Road (now Lexington Avenue). Although Hamilton had orders from Gen. Henry Knox to rally his men for a stand, Burr, in the name of Washington, countermanded Knox and led Hamilton, with little but the clothes on his back, two cannons and his men, by a concealed path up the west side of the island to freshly dug entrenchments at Harlem Heights. Burr most likely saved Hamilton’s life.

The British built defenses across northern Manhattan, which they now occupied. On September 20, fanned by high winds, a fire broke out at midnight in a frame house along the waterfront near Whitehall Slip. Four hundred and ninety-three houses—one-fourth of the city’s buildings—were destroyed before British soldiers and sailors and townspeople put out the flames. Though the British accused Washington of setting the fire, no evidence has ever been found to link him to it. In a letter to his cousin Lund at Mount Vernon, Washington wrote: “Providence, or some good honest fellow, has done more for us than we were disposed to do for ourselves.”

By mid-October, the American army had withdrawn across the Harlem River north to White Plains in Westchester County. There, on October 28, the British caught up with them. Behind hastily built earthworks, Hamilton’s artillerymen crouched tensely as Hessians unleashed a bayonet charge up a wooded slope. Hamilton’s gunners, flanked by Maryland and New York troops, repulsed the assault, causing heavy casualties, before being driven farther north.

Cold weather pinched the toes and numbed the fingers of Hamilton’s soldiers as they dug embankments. His pay book indicates he was desperately trying to round up enough shoes for his barefoot, frostbitten men. Meanwhile, an expected British attack did not materialize. Instead, the redcoats and Hessians stormed the last American stronghold on ManhattanIsland, FortWashington, at present-day 181st Street, where 2,818 besieged Americans surrendered on November 16. Three days later, the British force crossed the Hudson and attacked Fort Lee on the New Jersey shore near the present-day GeorgeWashingtonBridge. The Americans escaped, evacuating the fort so quickly they left behind 146 precious cannons, 2,800 muskets and 400,000 cartridges.

In early November, Captain Hamilton and his men had been ordered up the Hudson River to Peekskill to join a column led by Lord Stirling. The combined forces crossed the Hudson to meet Washington and, as the commander in chief observed, his 3,400 “much broken and dispirited” men, in Hackensack, New Jersey.

Hamilton hitched horses to his two remaining 6-pound guns and marched his gun crews 20 miles in one day to the RaritanRiver. Rattling through Elizabethtown, he passed the ElizabethtownAcademy where, only three years earlier, his greatest concern had been Latin and Greek declensions.

Dug in near Washington’s Hackensack headquarters on November 20, Hamilton was startled by the sudden appearance of his friend Hercules Mulligan, who, to Hamilton’s great dismay, had been captured some three months earlier at the Battle of Long Island. Mulligan had been determined a “gentleman” after his arrest and released on his honor not to leave New York City. After a joyous reunion, Hamilton evidently persuaded Mulligan to return to New York City and to act, as Mulligan later put it, as a “confidential correspondent of the commander-in-chief”—a spy.

After pausing to await Gen. Sir William Howe, the British resumed their onslaught. On November 29, a force of about 4,000, double that of the Americans, arrived at a spot across the Raritan River from Washington’s encampment. While American troops tore up the planks of the NewBridge, Hamilton and his guns kept up a hail of grapeshot.

For several hours, the slight, boyish-looking captain could be seen yelling, “Fire! Fire!” to his gun crews, racing home bags of grapeshot, then quickly repositioning the recoiling guns. Hamilton kept at it until Washington and his men were safely away toward Princeton. Halfway there, the general dispatched a brief message by express rider to Congress in Philadelphia: “The enemy appeared in several parties on the heights opposite Brunswick and were advancing in a large body toward the [Raritan] crossing place. We had a smart cannonade whilst we were parading our men.”

Washington asked one of his aides to tell him which commander had halted his pursuers. The man replied that he had “noticed a youth, a mere stripling, small, slender, almost delicate in frame, marching, with a cocked hat pulled down over his eyes, apparently lost in thought, with his hand resting on a cannon, and every now and then patting it, as if it were a favorite horse or a pet plaything.” Washington’s stepgrandson Daniel Parke Custis later wrote that Washington was “charmed by the brilliant courage and admirable skill” of the then 21-year-old Hamilton, who led his company into Princeton the morning of December 2. Another of Washington’s officers noted that “it was a model of discipline; at their head was a boy, and I wondered at his youth, but what was my surprise when he was pointed out to me as that Hamilton of whom we had already heard so much.”

After losing New Jersey to the British, Washington ordered his army into every boat and barge for 60 miles to cross the Delaware River into Pennsylvania’s BucksCounty. Ashivering Hamilton and his gunners made passage in a Durham ore boat, joining artillery already ranged along the western bank. Whenever British patrols ventured too near the water, Hamilton’s and the other artillerymen repulsed them with brisk fire. The weather grew steadily colder. General Howe said he found it “too severe to keep the field.” Returning to New York City with his redcoats, he left a brigade of Hessians to winter at Trenton.

In command of the brigade, Howe placed Col. Johann Gottlieb Rall, whose troops had slaughtered retreating Americans on Long Island and at FortWashington on Manhattan. His regiments had a reputation for plunder and worse. Reports that the Hessians had raped several women, including a 15-year-old girl, galvanized New Jersey farmers, who had been reluctant to help the American army. Now they formed militia bands to ambush Hessian patrols and British scouting parties around Trenton. “We have not slept one night in peace since we came to this place,” one Hessian officer moaned.

Washington now faced a vexing problem: the enlistments of his 3,400 Continental troops expired at midnight New Year’s Eve; he decided to attack the Trenton Hessians while they slept off the effects of their Christmas celebration. After so many setbacks, it was a risky gambit; defeat could mean the end of the American cause. But a victory, even over a small outpost, might inspire lagging Patriots, cow Loyalists, encourage reenlistments and drive back the British—in short, keep the Revolution alive. The main assault force was made up of tested veterans. Henry Knox, Nathanael Greene, James Monroe, John Sullivan and Alexander Hamilton, future leaders of America’s republic, huddled around a campfire at McKonkey’s Ferry the frigid afternoon of December 25, 1776, to get their orders. Hamilton and his men had blankets wrapped around them as they hefted two 6-pounders and their cases of shot and shells onto the 9-foot-wide, 60- foot-long Durham iron-ore barges they had commandeered, then pushed and pulled their horses aboard. Nineteen-yearold James Wilkinson noted in his journal that footprints down to the river were “tinged here and there with blood from the feet of the men who wore broken shoes.” Ship cap tain John Glover ordered the first boatloads to push off at 2 a.m. Snow and sleet stung Hamilton’s eyes.

Tramping past darkened farmhouses for 12 miles, Hamilton’s company led Nathanael Greene’s division as it swung off to the east to skirt the town. One mile north of Trenton, Greene halted the column. At precisely 8 in the morning, Hamilton unleashed his artillery on the Hessian outpost. Three minutes later, American infantry poured into town. Driving back Hessian pickets with their bayonets, they charged into the old British barracks to confront groggy Hessians at gunpoint. Some attempted to regroup and counterattack, but Hamilton and his guns were waiting for them. Firing in tandem, Hamilton’s cannons cut down the Hessians with murderous sheets of grapeshot. The mercenaries sought cover behind houses but were driven back by Virginia riflemen, who stormed into the houses and fired down from upstairs windows. Hessian artillerymen managed to get off only 13 rounds from two brass fieldpieces before Hamilton’s gunners cut them in two. Riding back and forth behind the guns, Washington saw for himself the brutal courage and skillful discipline of this youthful artillery captain.

The Hessians’ two best regiments surrendered, but a third escaped. As the Americans recrossed the Delaware, both they and their prisoners, nearly 1,000 in all, had to stomp their feet to break up the ice that was forming on the river. Five men froze to death.

Stung by the defeat, British field commander Lord Cornwallis raced across New Jersey with battle-seasoned grenadiers to retaliate. Americans with $10 gold reenlistment bonuses in their pockets recrossed the river to intercept them. When the British halted along a three-mile stretch of Assunpink Creek outside Trenton and across from the Americans, Washington duped British pickets by ordering a rear guard to tend roaring campfires and to dig noisily through the night while his main force slipped away.

At 1 a.m., January 2, 1777, their numbers reduced from 69 to 25 by death, desertion and expired enlistments, Hamilton and his men wrapped rags around the wheels of their cannons to muffle noise, and headed north. They reached the south end of Princeton at sunrise, to face a brigade—some 700 men—of British light infantry. As the two forces raced for high ground, American general Hugh Mercer fell with seven bayonet wounds. The Americans retreated from a British bayonet charge. Then Washington himself galloped onto the battlefield with a division of Pennsylvania militia, surrounding the now outnumbered British. Some 200 redcoats ran to Nassau Hall, the main building at PrincetonCollege. By the time Hamilton set up his two cannons, the British had begun firing from the windows of the red sandstone edifice. College tradition holds that one of Hamilton’s 6-pound balls shattered a window, flew through the chapel and beheaded a portrait of King George II. Under Hamilton’s fierce cannonade, the British soon surrendered.

In the wake of twin victories within ten days, at Trenton and Princeton, militia volunteers swarmed to the American standard, far more than could be fed, clothed or armed. Washington’s shorthanded staff was ill-equipped to coordinate logistics. In the four months since the British onslaught had begun, 300 American officers had been killed or captured. “At present,” Washington complained, “my time is so taken up at my desk that I am obliged to neglect many other essential parts of my duty. It is absolutely necessary for me to have persons [who] can think for me as well as execute orders. . . . As to military knowledge, I do not expect to find gentlemen much skilled in it. If they can write a good letter, write quick, are methodical and diligent, it is all I expect to find in my aides.”

He would get all that and more. In January, shortly after the army was led into winter quarters at Morristown, New Jersey, Nathanael Greene invited Hamilton, who had just turned 22, to dinner at Washington’s headquarters. There, Washington invited the young artillery officer to join his staff. The appointment carried a promotion from captain to lieutenant colonel, and this time Hamilton did not hesitate. On March 1, 1777, he turned over the command of his artillery company to Lt. Thomas Thompson—a sergeant whom, against all precedent, he had promoted to officer rank—and joined Washington’s headquarters staff.

It would prove a profound relationship.

“During a long series of years, in war and in peace, Washington enjoyed the advantages of Hamilton’s eminent talents, integrity and felicity, and these qualities fixed [Hamilton] in [Washington’s] confidence to the last hour of his life,” wrote Massachusetts Senator Timothy Pickering in 1804.Hamilton, the impecunious abandoned son, and Washington, the patriarch without a son, had begun a mutually dependent relationship that would endure for nearly 25 years— years corresponding to the birth, adolescence and coming to maturity of the United States of America.

Hamilton would become inspector general of the U.S. Army and in that capacity founded the U.S. Navy. Along with James Madison and John Jay, he wrote the Federalist Papers, essays that helped gain popular support for the then-proposed Constitution. In 1789, he became the first Secretary of the Treasury, under President Washington and almost single-handedly created the U.S. Mint, the stock and bond markets and the concept of the modern corporation.

After the death of Washington on December 14, 1799, Hamilton worked secretly, though assiduously, to prevent the reelection of John Adams as well as the election of Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr. Burr obtained a copy of a Hamilton letter that branded Adams an “eccentric” lacking in “sound judgment” and got it published in newspapers all over America. In the 1801 election, Jefferson and Burr tied in the Electoral College, and Congress made Jefferson president, with Burr his vice president. Hamilton, his political career in tatters, founded the New York Evening Post newspaper, which he used to attack the new administration. In the 1804 New York gubernatorial election, Hamilton opposed Aaron Burr’s bid to replace Governor George Clinton. With Hamilton’s help, Clinton won.

When he heard that Hamilton had called him “a dangerous man, and one who ought not to be trusted with the reins of government,” Burr demanded a written apology or satisfaction in a duel. On the morning of Thursday, July 11, 1804, on a cliff in Weehawken, New Jersey, Hamilton faced the man who had rescued him 28 years earlier in Manhattan. Hamilton told his second, Nathaniel Pendleton, that he intended to fire into the air so as to end the affair with honor but without bloodshed. Burr made no such promise. Ashot rang out. Burr’s bullet struck Hamilton in the right side, tearing through his liver. Hamilton’s pistol went off a split second later, snapping a twig overhead. Thirty-six hours later, Alexander Hamilton was dead. He was 49 years old.