The Mooncake: A Treat, a Bribe or a Tradition Whose Time Has Passed?

Is the mooncake just going through a phase or are these new variations on the Chinese treat here to stay?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/mooncakefestival-42-16989956-alt-FLASH.jpg)

Sienna Parulis-Cook had been living in China for nine months when, in the summer of 2007, she found herself in the belly of the country’s $1.42 billion mooncake industry.

A Chinese bakery chain had hired the 22-year-old American to market their contemporary take on the traditional palm-sized pastry that’s widely popular in China. Soon Parulis-Cook was hawking mooncakes door-to-door at Beijing restaurants, and advertising them to multinational corporations that were keen to delight their Chinese employees.

“It opened up a whole new world of mooncakes,” said Parulis-Cook from Beijing.

Growing up in Vermont, Parulis-Cook had read tales of mooncake that made the palm-sized delicacy sound “romantic and delicious.” But in Beijing, she discovered that mooncake traditions — like modern China itself — have changed considerably in a generation.

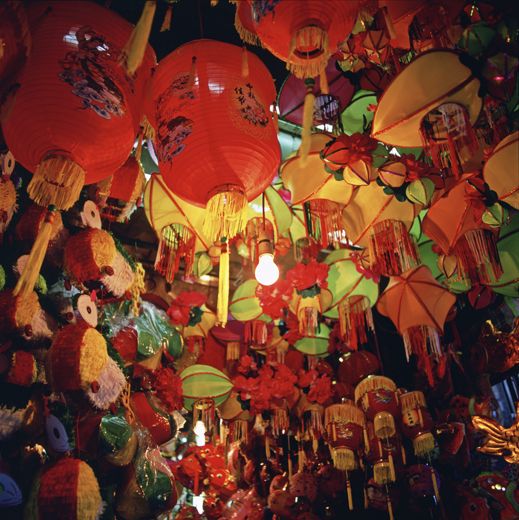

Every fall, people across China and the Asia-Pacific region buy mooncakes to mark the mid-autumn festival, an event that typically features activities like dancing and lantern-lighting. But while the cakes were traditionally baked during harvest festivals as symbols of fertility, today they are mainly produced in factories. Traditional mooncake ingredients like green bean and salted egg are yielding to trendier ones like chocolate and ice cream.

Her employer was selling boxes of mooncakes for the equivalent of up to $50, and the boxes featured pouches designed to hold business cards. Also: Some of those “mooncakes” were actually just mooncake-shaped hunks of chocolate.

The treats are increasingly seen as markers of status, signs of excessive consumption or even tools that abet corruption. Parulis-Cook says that in 2006, city authorities in Beijing banned the sale of mooncakes with “accessories,” in an attempt to prevent bribery and discourage wasteful behavior. Last year, the American law firm Baker & McKenzie cautioned western investors about the ethical implications of giving mooncakes and other gifts to Chinese clients, business associates or government officials. The title page of their report asked: “WHEN IS A MOONCAKE A BRIBE?”

The traditions of the mid-autumn festival, which began this past weekend, has been well documented by scholars, but it’s hard to definitively say how, when or why mooncakes came to be.

A mooncake is usually the size and shape of a hockey puck, although some are square or shaped like animals from the zodiac calendar. (Chinese state media also reported last year on a mooncake measuring 80 centimeters, or about two and a half feet, in diameter.) Mooncakes may be baked, or not, but they are almost always stamped with a type of seal or emblem. In some cases the seal is a form of corporate marketing: On a recent morning at Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi International Airport, I purchased a coffee-and-egg mooncake at Starbucks, and the seal matched the green-and-black logo on the store’s façade.

Kian Lam Kho, a Chinese-American food blogger who grew up in Singapore and lives in New York City, says he’s not sure what to think about the commodification of the mooncake. “On the one hand the competition in commerce is generating a lot of creativity among the mooncake vendors to make new and innovative flavors,” he told me by email. “On the other hand I believe the commercialization has trivialized the spirit of the celebration.”

The only comprehensive mooncake study appears to be Sienna Parulis-Cook’s 2009 masters’ thesis for the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. In the 34-page paper, she cites a widely-held Chinese anecdote explaining how mooncakes were once “used by rebels to promulgate a major uprising against the Yuan Dynasty.” Mooncakes were “big business” in urban China by the late nineteenth century, she adds, and about a century ago, they were stamped with patriotic slogans and incorporated into national day celebrations.

Mooncakes can be emotionally moving. Wang Xiao Jian, a 27-year-old woman in Beijing, told me of a song that her late-grandfather, a tailor, once sang to her in the years leading up to his death. It chronicled how soldiers in China’s Red Army were retuning to their families and looking forward to teaching their grandchildren how to make mooncake. “It’s the best memory grandpa gave me," she said.

Although salted egg and lotus seed-green bean are among China’s most popular mooncake fillings, there are regional variations, such as nutty mooncakes in Beijing and extra-flaky ones in the eastern province of Suzhou. Mooncakes also vary widely across the Asia-Pacific region. Hong Kong, for example, has not yet seen “any mooncake having meat,” says Dr. Chan Yuk Wak, a professor at Hong Kong’s city university, while in Vietnam, traditional mooncakes are loaded with sausage, pork and lard.

Other, less official, mooncake tales abound. A brochure I picked up in the lobby of a hotel in Hanoi claims mooncakes were once “served only in Royal families.” An English-language chapbook about the mid-autumn festival in Vietnam says mooncakes are best eaten three days after baking so that oil can better seep into their shells. And the website chinatownology.com cites a legend asserting that mooncakes were “instrumental” in China’s overthrow of the Mongol dynasty because residents passed notes to each other, hidden in mooncakes, calling for an uprising.

But a common refrain across the region is that teens and 20-somethings are less excited about mooncake than their parents once were. According to Parulis-Cook, that could be because they don’t like the taste, don’t want to gain weight or are worried about food safety issues. Some young people in China and Hong Kong now eat uber-trendy mooncakes with names like “strawberry balsamic” or “Snowskin Banana with low-fat yoghurt.” Others eat none at all.

Nguyen Manh Hung, a 29-year-old Vietnamese chef, says he would never give his mother, whom he calls “very traditional,” a mooncake with a trendy filling like sticky rice or chocolate. However, he also thinks culinary innovation is healthy, and he buys more-adventurous mooncakes for his own nuclear family. “The traditional mooncakes are boring, and younger people don’t like to eat them too much,” he told me at the Hanoi Cooking Centre. “Nowadays it’s fashionable to want something different.”

Once a year, Hung bakes his own. It’s a labor of love: Sugar water must be cooked and then distilled in water for an entire year before it can be incorporated into batter, and assembling a traditional Vietnamese mooncake — which can include about 10 different salted ingredients — takes up to two days.

He may be in the vanguard of a shift toward DIY mooncakes. Kho, the New York-based food blogger, says he bakes his own mooncakes in Harlem. And in Beijing, editors at the Chinese food magazine Betty’s Kitchen tell Sienna Parulis-Cook, the American mooncake connoisseur, that although most apartments in China don’t come with ovens, many Chinese are buying stand-along ones and learning how to bake sweets, including cookies and mooncakes.

Parulis-Cook, now 28 and a dining editor for a Beijing-based English-language magazine, once baked ice cream mooncakes with help from a recipe she found in Betty’s Kitchen. But she doesn’t much care for the taste of most mooncakes, and usually re-gifts the eight to 10 mooncakes she receives each lunar autumn from business associates to her Chinese colleagues.

Still she adds, “If I get more than my boss, it makes me feel really influential.”