Why Mass Incarceration Defines Us As a Society

Bryan Stevenson, the winner of the Smithsonian American Ingenuity Award in social justice, has taken his fight all the way to the Supreme Court

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Ingenuity-Awards-Bryan-Stevenson-631.jpg)

It is late in the afternoon in Montgomery. The banks of the Alabama River are largely deserted. Bryan Stevenson and I walk slowly up the cobblestones from the expanse of the river into the city. We pass through a small, gloomy tunnel beneath some railway tracks, climb a slight incline and stand at the head of Commerce Street, which runs into the heart of Alabama’s capital. The walk was one of the most notorious in the antebellum South.

“This street was the most active slave-trading space in America for almost a decade,” Stevenson says. Four slave depots stood nearby. “They would bring people off the boat. They would parade them up the street in chains. White plantation owners and local slave traders would get on the sidewalks. They’d watch them as they went up the street. Then they would follow behind up to the circle. And that is when they would have their slave auctions.

“Anybody they didn’t sell that day they would keep in these slave depots,” he continues.

We walk past a monument to the Confederate flag as we retrace the steps taken by tens of thousands of slaves who were chained together in coffles. The coffles could include 100 or more men, women and children, all herded by traders who carried guns and whips. Once they reached Court Square, the slaves were sold. We stand in the square. A bronze fountain with a statue of the Goddess of Liberty spews jets of water in the plaza.

“Montgomery was notorious for not having rules that required slave traders to prove that the person had been formally enslaved,” Stevenson says. “You could kidnap free black people, bring them to Montgomery and sell them. They also did not have rules that restricted the purchasing of partial families.”

We fall silent. It was here in this square—a square adorned with a historical marker celebrating the presence in Montgomery of Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy—that men and women fell to their knees weeping and beseeched slave-holders not to separate them from their husbands, wives or children. It was here that girls and boys screamed as their fathers or mothers were taken from them.

“This whole street is rich with this history,” he says. “But nobody wants to talk about this slavery stuff. Nobody.” He wants to start a campaign to erect monuments to that history, on the sites of lynchings, slave auctions and slave depots. “When we start talking about it, people will be outraged. They will be provoked. They will be angry.”

Stevenson expects anger because he wants to discuss the explosive rise in inmate populations, the disproportionate use of the death penalty against people of color and the use of life sentences against minors as part of a continuum running through the South’s ugly history of racial inequality, from slavery to Jim Crow to lynching.

Equating the enslavement of innocents with the imprisonment of convicted criminals is apt to be widely resisted, but he sees it as a natural progression of his work. Over the past quarter-century, Stevenson has become perhaps the most important advocate for death-row inmates in the United States. But this year, his work on behalf of incarcerated minors thrust him into the spotlight. Marshaling scientific and criminological data, he has argued for a new understanding of adolescents and culpability. His efforts culminated this past June in a Supreme Court ruling effectively barring mandatory life sentences without parole for minors. As a result, approximately 2,000 such cases in the United States may be reviewed.

***

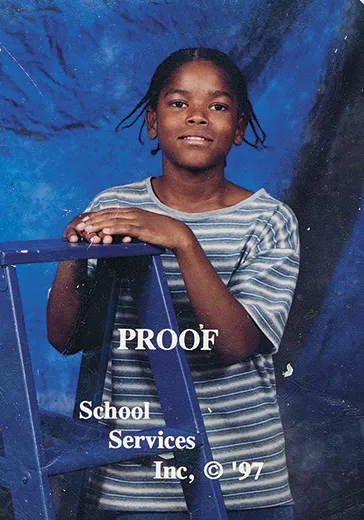

Stevenson’s effort began with detailed research: Among more than 2,000 juveniles (age 17 or younger) who had been sentenced to life in prison without parole, he and staff members at the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), the nonprofit law firm he established in 1989, documented 73 involving defendants as young as 13 and 14. Children of color, he found, tended to be sentenced more harshly.

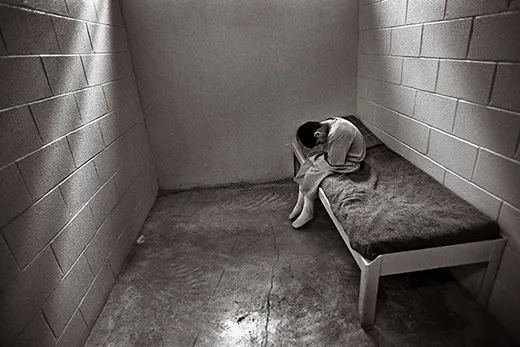

“The data made clear that the criminal justice system was not protecting children, as is done in every other area of the law,” he says. So he began developing legal arguments “that these condemned children were still children.”

Stevenson first made those arguments before the Supreme Court in 2009, in a case involving a 13-year-old who had been convicted in Florida of sexual battery and sentenced to life in prison without parole. The court declined to rule in that case—but upheld Stevenson’s reasoning in a similar case it had heard the same day, Graham v. Florida, ruling that sentencing a juvenile to life without parole for crimes other than murder violated the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

Last June, in two cases brought by Stevenson, the court erased the exception for murder. Miller v. Alabama and Jackson v. Hobbs centered on defendants who were 14 when they were arrested. Evan Miller, from Alabama, used drugs and alcohol late into the night with his 52-year-old neighbor before beating him with a baseball bat in 2003 and setting his residence on fire. Kuntrell Jackson, from Arkansas, took part in a 1999 video-store robbery with two older boys, one of whom shot the clerk to death.

The states argued that children and adults are not so different that a mandatory sentence of life imprisonment without parole is inappropriate.

Stevenson’s approach was to argue that other areas of the law already recognized significant differences, noting that children’s brains and adults’ are physiologically distinct. This, he said, is why children are barred from buying alcohol, serving on juries or voting. He argued that the horrific abuse and neglect that drove many of these children to commit crimes were beyond their control. He said science, precedent and consensus among the majority of states confirmed that condemning a child to die in prison, without ever having a chance to prove that he or she had been rehabilitated, constituted cruel and unusual punishment. “It could be argued that every person is more than the worst thing they’ve ever done,” he told the court. “But what this court has said is that children are uniquely more than their worst act.”

The court agreed, 5 to 4, in a landmark decision.

“If ever a pathological background might have contributed to a 14-year-old’s commission of a crime, it is here,” wrote Justice Elena Kagan, author of the court’s opinion in Miller. “Miller’s stepfather abused him; his alcoholic and drug-addicted mother neglected him; he had been in and out of foster care as a result; and he had tried to kill himself four times, the first when he should have been in kindergarten.” Children “are constitutionally different from adults for purposes of sentencing,” she added, because “juveniles have diminished culpability and greater prospects for reform.”

States are still determining how the ruling will affect juveniles in their prisons. “I don’t advocate that young people who kill should be shielded from punishment. Sometimes the necessary intervention with a youth who has committed a serious crime will require long-term incarceration or confinement,” Stevenson says. “However, I don’t think we can throw children away.” Sentences “should recognize that these young people will change.”

***

Stevenson, 52, is soft-spoken, formal in a shirt and tie, reserved. He carries with him the cadence and eloquence of a preacher and the palpable sorrow that comes with a lifetime advocating for the condemned. He commutes to New York, where he is a professor of clinical law at New York University School of Law. In Montgomery he lives alone, spends 12, sometimes 14 hours a day working out of his office and escapes, too rarely, into music. “I have a piano, which provides some therapy,” he says. “I am mindful, most of the time, of the virtues of regular exercise. I grow citrus in pots in my backyard. That’s pretty much it.”

He grew up in rural Milton, Delaware, where he began his education in a “colored” school and other forms of discrimination, such as black and white entrances to the doctor’s and dentist’s offices, prevailed. But he was raised in the embrace of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and his parents worked and provided an economic and emo- tional stability that many around him lacked. He played the piano during worship. His father and his sister, who is a music teacher, still live in Delaware. His brother teaches at the University of Pennsylvania. His mother died in 1999.

When Stevenson was 16, his maternal grandfather was murdered in Philadelphia by four juveniles; they were convicted and sentenced to prison. Stevenson does not know what has become of them. “Losing a loved one is traumatic, painful and disorienting,” he says. But ultimately the episode, and others in which relatives or friends became crime victims, “reinforced for me the primacy of responding to the conditions of hopelessness and despair that create crime.”

He attended a Christian college, Eastern University in Wayne, Pennsylvania, where he directed the gospel choir. He did not, he says, “step into a world where you were not centered around faith” until he entered Harvard Law School in 1981. The world of privilege and entitlement left him alienated, as did the study of torts and civil procedure. But in January 1983, he went to Atlanta for a month-long internship with an organization now called the Southern Center for Human Rights. The lawyers there defended inmates on death row, many of whom, Stevenson discovered, had been railroaded in flawed trials. He found his calling. He returned to the center when he graduated and became a staff attorney. He spent his first year of work sleeping on a borrowed couch.

He found himself frequently in Alabama, which sentences more people to death per capita than any other state. There is no state-funded program to provide legal assistance to death-row prisoners, meaning half of the condemned were represented by court-appointed lawyers whose compen- sation was capped at $1,000. Stevenson’s reviews of trial records convinced him that few of the condemned ever had an adequate defense. He got the conviction of one death-row inmate, Walter McMillian, overturned by the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals. His next case, he says, led him to establish EJI.

It began with a collect call from Herbert Richardson, a death-row inmate at Holman State Prison. Richardson, a disturbed Vietnam combat veteran, had left an explosive device on the porch of an estranged girlfriend; it killed a young girl. His execution was to be held in 30 days. Stevenson, after a second phone call, filed for an emergency stay of execution, which the state rejected.

“He never really got representation until we jumped in,” Stevenson says.

He went to the prison on the day of the execution, which was scheduled for midnight. He found his client surrounded by a half-dozen family members, including the woman who had married him the week before. Richardson repeatedly asked Stevenson to make sure his wife received the American flag he would be given as a veteran.

“It was time for the visit to end,” Stevenson recalls. But the visitation officer, a female guard, was “clearly emotionally unprepared to make these people leave.” When she insisted, Stevenson says, Richardson’s wife grabbed her husband. “She says, ‘I’m not leaving.’ Other people don’t know what to do. They are holding on to him.” The guard left, but her superiors sent her back in. “She has tears running down her face. She looks to me and says, ‘Please, please help me.’ ”

He began to hum a hymn. The room went still. The family started singing the words. Stevenson went over to the wife and said, “We’re going to have to let him go.” She did.

He then walked with Richardson to the execution chamber.

“Bryan, it has been so strange,” the condemned man said. “All day long people have been saying to me, ‘What can I do to help you?’ I got up this morning, ‘What can I get you for breakfast? What can I get you for lunch? What can I get you for dinner? Can I get you some stamps to mail your last letters? Do you need the phone? Do you need water? Do you need coffee? How can we help you?’ More people have said what can they do to help me in the last 14 hours of my life than they ever did” before.

“You never got the help you needed,” Stevenson told him. And he made Richardson a promise: “I will try and keep as many people out of this situation as possible.”

Richardson had asked the guards to play “The Old Rugged Cross” before he died. As he was strapped into the electric chair and hooded, the hymn began to blare out from a cassette player. Then the warden pulled the switch.

“Do you think we should rape people who rape?” Stevenson asks. “We don’t rape rapists, because we think about the person who would have to commit the rape. Should we assault people who have committed assault? We can’t imagine replicating a rape or an assault and hold onto our dignity, integrity and civility. But because we think we have found a way to kill people that is civilized and decent, we are comfortable.”

***

Stevenson made good on his promise by founding EJI, whose work has reversed the death sentences of more than 75 inmates in Alabama. Only in the last year has he put an EJI sign on the building, he says, “because of concerns about hostility to what we do.”

His friend Paul Farmer, the physi- cian and international health specialist (and a member of EJI’s board), says Stevenson is “running against an undercurrent of censorious opinion that we don’t face in health care. But this is his life’s work. He’s very compassionate, and he’s very tough-minded. That’s a rare combination.”

Eva Ansley, who has been Stevenson’s operations manager for over 25 years, says the two most striking things about him are his kindness and constancy of purpose. “I have never known Bryan to get off track, to lose sight of the clients we serve or to have an agenda that is about anything other than standing with people who stand alone,” she says. “After all these years, I keep expecting to see him become fed up or impatient or something with all the requests put to him or the demands placed on him, but he never does. Never.”

EJI’s office is in a building that once housed a school for whites seeking to defy integration. The building is in the same neighborhood as Montgomery’s slave depots. For Stevenson, that history matters.

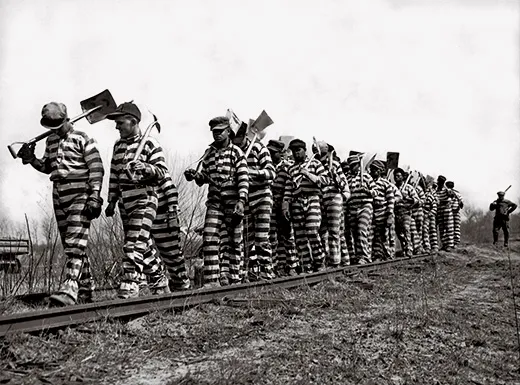

Mass incarceration defines us as a society, Stevenson argues, the way slavery once did. The United States has less than 5 percent of the world’s population but imprisons a quarter of the world’s inmates. Most of those 2.3 million inmates are people of color. One out of every three black men in their 20s is in jail or prison, on probation or parole, or bound in some other way to the criminal justice system. Once again families are broken apart. Once again huge numbers of black men are disenfranchised, because of their criminal records. Once again people are locked out of the political and economic system. Once again we harbor within our midst black outcasts, pariahs. As the poet Yusef Komunyakaa said: “The cell block has replaced the auction block.”

In opening a discussion of American justice and America’s racial history, Stevenson hopes to help create a common national narrative, one built finally around truth rather than on the cultivated myths of the past, that will allow blacks and whites finally to move forward. It’s an ambitious goal, but he is exceptionally persuasive. When he gave a TED talk about his work last March, he received what TED leader Chris Anderson called one of the longest and loudest ovations in the conference’s history—plus pledges of $1.2 million to EJI.

Stevenson turns frequently to the Bible. He quotes to me from the Gospel of John, where Jesus says of the woman who committed adultery: “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her.” He tells me an elderly black woman once called him a “stone catcher.”

“There is no such thing as being a Christian and not being a stone catcher,” he says. “But that is exhausting. You’re not going to catch them all. And it hurts. If it doesn’t make you sad to have to do that, then you don’t understand what it means to be engaged in an act of faith....But if you have the right relationship to it, it is less of a burden, finally, than a blessing. It makes you feel stronger.

“These young kids who I have sometimes pulled close to me, there is nothing more affirming than that moment. It may not carry them as long as I want. But I feel as if my humanity is at its clearest and most vibrant.”

It is the system he is taking on now, not its symptoms. “You have to understand the institutions that are shaping and controlling people of color,” he says.

“Is your work a ministry?” I ask.

“I would not run from that description.”