Each February, the color pink is a bold sign that the season of love has arrived. Now filled with blush-colored Hallmark cards featuring cute puppies and kittens, Valentine’s Day has evolved in stark contrast to its origins. The three-day Roman feast allegedly marked by animal sacrifice is certainly more R-rated by today’s standards.

Thankfully, people simply purchase fluffy, rose-tinted Teddy bears for their special someone instead these days. You’d be hard-pressed to find a rosy grizzly in nature, however, so why not celebrate this Valentine’s Day by learning about 14 animals who rock both soft and vibrant shades of pink, naturally.

Axolotls Have Hot Pink External Gills

Captive axolotls are known for their pale pink-white bodies and flashy, spiky, hot-pink hair-do—that isn't hair at all. The crown of feathery prongs emerging from the base of their head is actually its gills. Axolotls have four genes that influence their color. Those with a white-pink body rely on a recessive gene that during embryonic development prevents pigment cells meant to darken their body from taking effect.

But rose-hued axolotls won't pop up in the wilderness. For starters, wild axolotls are an olive-brown color, and they only live in waterways in Xochimilco, Mexico. These critters are critically endangered but persist in captivity as research subjects or unique pets.

Rare Fuschia Oblong-Winged Katydids Stand Out in a Crowd

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/39/a1/39a18ba3-db28-4a2c-a262-33bdf71a0fd9/5996694338_12df88bbc4_b.jpg)

Katydids have a reputation for being brown or green, but some species shatter the stereotype with a bright pink flair. Oblong-winged katydids (Amblycorypha oblongifolia) are one of those species. Breeding experiments suggest this discrepancy isn’t due to a genetic mutation. When a green individual mates with a pink one, they make blush-colored children half the time. So why are fewer of these pink katydids seen?

Blame the power of camouflage, which gives green katydids that resemble leaves a survival advantage in most areas. In contrast, easy-to-spot pink individuals are picked off by predators.

Beware of the 'Purple People Eater'

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8a/d8/8ad89a51-d9d0-4c78-94d0-c36e3c5b6e34/8690256488_ca01a01721_b.jpg)

The mauve stinger jellyfish (Pelagia noctiluca) proudly displays brightly pigmented hues, dazzling the beholder with purple, yellow and even pink varieties. P. noctiluca roughly translates to “night light” in German, named for its ability to leave a glowing trail of bioluminescent mucous behind if frightened. They have stout bell- or umbrella-shaped “bodies” measuring between 3 to 12 centimeters, with long tentacles dangling below.

In Australia, these jellies have a quite shocking nickname: the purple people eater—and for good reason. They’re covered with stinging cells called nematocysts that are able to paralyze their small prey, including planktonic crustaceans and fish larvae, and give humans localized pain.

Amazon River Dolphins May Get Pinker From Battle

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fc/83/fc83fc93-b7dc-43aa-8258-5fe8168a507f/gettyimages-953400668.jpg)

When Amazon river dolphins (Inia geoffrensis) are young, they pretty much look almost like the average bottlenose dolphin one might see at a zoo with a few key differences. They are born with sleek, gray bodies, but feature long, thin snouts and ridge-like humps where a typical dorsal fin would be. But when they grow up, they become even more distinct from good ol’ Flipper.

Some adults in the species develop a gorgeous blush-pink color, hence their nickname “pink river dolphin.” How exactly these animals, also called boto, go from gray in their youth to pink when they mature is unknown. But there is one rather brutally compelling theory: they beat each other up.

Males, who are bigger and more aggressive, tend to also look pinker than the females. It’s possible, then, that their color comes from their scar tissue that appears as they heal from battle. Another idea is that the adults become pink to camouflage themselves in murky red waters to hide from prey. Considering they’re an endangered species, impacted by human hunting and development, that kind of adaptation might be crucial for their survival.

The Rose-Feathered Galah Will Make You Say Ooh-La-La

Cockatoos might have the most stylish hairdos in the animal kingdom, and the pink galah’s short, white-feathered crest is among them. Like other parrots, the galah’s raspberry-colored neck, breast and underwings are caused by psittacofulvins, pigmented molecules in their feathers produce color absorbed from light. These molecules are unique to parrots, whereas most other birds get their colored plumage from light-absorbing carotenoid pigments found in their diet, not within their feathers.

Those searching for wild galahs (Eolophus roseicapilla) will need to travel to two locations in Oceania: mainland Australia or a small region in northern New Zealand.

This Super-Pink Sea Slug Eats Tiny Rose-Colored Creatures

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e0/30/e030b234-a922-447b-9e01-971a882dbee4/49881763262_55da21a0b0_b.jpg)

Despite looking more like a sea anemone or some kind of squishy, spiky stress ball, the Hopkins’ rose nudibranch (Okenia rosacea) is actually a sea slug—and please don’t give it a squeeze. Aptly named, this North America-based, one-inch-long sea critter is as impossibly pink, save for its white-tipped papillae. Nudibranches use their colors to warn predators that making a meal out of them would lead to toxic consequences.

Unlike other sea slugs, nudibranchs feast on certain creatures, and the Hopkins’ rose variety gets its beautiful color from its choice prey: tiny pink bryozoans, or moss animals. Bryozoans are colonial animals, meaning they live in colonies where individual organisms connect in units called zooids. These Lego-like animals are no match for the Hopkins’ rose nudibranch, however, which has hook-like teeth made to pierce through bryozoans and gobble up the pink delicacies.

This Worm-Like Creature Is Actually a Lizard

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8f/a7/8fa7625e-943d-4397-9e8a-113a59107c8a/bipes_biporus.jpg)

Despite its blush-colored, noodle-like frame, the Mexican mole lizard (Bipes biporus) is neither a worm nor a snake. Instead of four legs, however, the reptile has just two tiny forelegs for digging while the rest of its body slithers along. Rarely emerging from the ground, the strange-looking lizard’s subterranean lifestyle causes it to have low levels of color-boosting melanin. This behavior leads to its baby-pink appearance, though it turns white as it matures.

The Mexican mole lizard belongs to a group of legless lizards called amphisbaenians. Of course, since it actually does have limbs, it also resides within a special three-species family called Bipedidae that have front legs, unlike the other amphisbaenians. Native to Baja California Peninsula in Mexico, these critters are hitched to a rather unsavory, baseless myth among locals. Some folks fear the lizard will crawl into certain exposed areas while relieving themselves.

A Fluffy, White Bat With Rosé-Toned Wings

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/44/6544464f-d8eb-4455-b4a0-82ab76fc1801/p1070111-northern-ghost-bat-diclidurus-albus.jpg)

Not to be mistaken for cotton ball hanging from the rafters, the northern ghost bat (Diclidurus albus) lives up to its name thanks to the soft white fur it sports. Once in the air, however, its translucent pink wing membranes, stretching from the forelimbs to the hindlimbs, are unmistakable. This coloring deviates from the darker membranes more commonly found among bats, helping the ghost bat stand out among its batty relatives.

Where the northern ghost bat’s name deceives is its geographical range. Not found in most of the Northern Hemisphere, instead, their habitat range includes Mexico, Central America, most of Brazil, parts of South America and across some Caribbean islands, including Trinidad.

The species is solitude save for breeding season, which happens to occur in January and February—just in time for the season of love, when members in groups as big as four step outside their bubbles to cozy up together during the day.

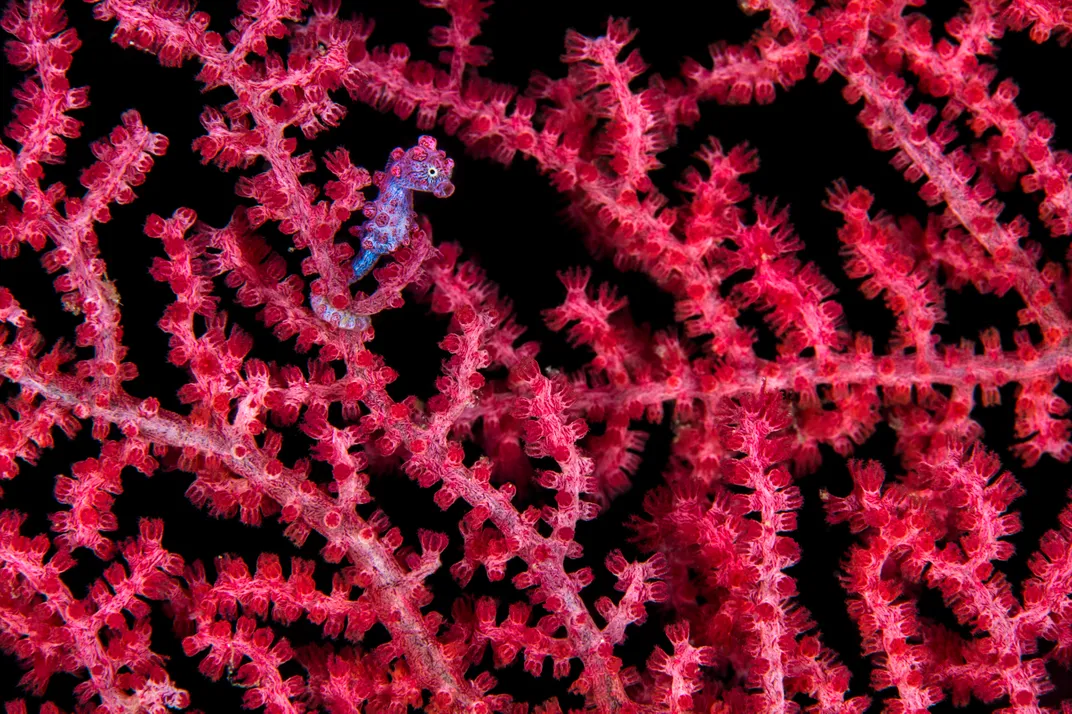

This Coral-Colored Seahorse Matches Its Home

Measuring just under an inch when fully grown, the Bargibant’s pygmy seahorse (Hippocampus bargibanti) doesn’t just rely on its small stature to hide from predators. They instead go one step further: matching their environment with the precision of an expert designer.

The species lives mainly in the Coral Triangle in the western Pacific Ocean, where they reside and feed on gorgonian corals. The color of the pygmy seahorses depends on the coral they live in during their youth. To match their vibrant coral home, they’re usually an orange-yellow mix or a red-pink fusion, with bumps called tubercles aiding their camouflage. It’s unclear yet if the seahorses can change colors if they take up residence elsewhere, or if their coloration lasts a lifetime.

A Mantis Disguised as a Beautiful Blossom

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9f/50/9f50525c-bbaf-4dce-83a3-fd26e92e170b/12089400405_b46f654ba2_b.jpg)

The orchid mantis (Hymenopus coronatus), found in Southeast Asia and Indonesia, uses its white body with ombré hints of pink and yellow hues to draw in other insects for a feast. This appearance, particularly stunning in their juvenile forms, is an example of aggressive mimicry where an animal blends in with its environment to catch prey off guard. However, the orchid mantis doesn’t actually look like any particular flower in its environment.

Rather, the orchid mantis’s unspecific nature is actually a boon. Instead of just attracting specific types of pollinators for the kill, the mantis keeps its menu wide open by appearing generic enough to bring in many unsuspecting insects. It doesn’t need to saddle-up next to blossoms to get the job done either; standing out in the open masquerading as a gorgeous orchid is enough to pull off the charade.

This Dashing Dragonfly Is No Damselfly in Distress

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3b/6c/3b6c68ee-a913-4caa-9cb5-6b92e37f7dc8/10139402245_5bec0cc5b6_o.jpg)

The roseate skimmer is an aptly named dragonfly—that is, for the males. As an animal that exhibits sexual dimorphism, the species’ mature males and females appear noticeably different from each other. The females are decidedly less colorful, taking on a brownish hue. The males, however, show off pink-purple bodies when they reach adulthood. A young male roseate skimmer (Orthemis ferruginea) is certainly a mama’s boy, having a similar appearance to the females before his own maturation.

The species can be found throughout the southern United States, from California to Florida. It also is located in Hawaii and parts of the Midwest and East Coast, Mexico, and Central America. Roseate skimmers prefer inland bodies of water where vegetation is plentiful, and decide to put their eggs even in tiny pools so long as the plants they desire to eat are around.

The Shocking Pink Dragon Millipede Lives Up to Its Name

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/02/44/0244c6aa-4a2f-491d-a119-24d512d32339/ef1hmx.jpg)

While the shocking pink dragon millipede (Desmoxytes purpurosea) is considerably smaller than dragons of lore, they are just as intimidating to their enemies as their fire-breathing namesakes. Resembling hot pink limousines of the insect world, the three-centimeter-long millipedes’ vibrant color serves as a warning to any would-be predator: stay away. They have glands that excrete hydrogen cyanide, a highly toxic acid. This strategy—using appearance to signal danger—is known as aposematic coloration.

Aposematic coloration is thought to be the reason for the pink dragon millipede’s coloring because it eats out in the open during the day, perhaps confident that its stunning appearance will dissuade other animals from eating it. The pink dragon millipede resides in northern Thailand. It is also one of the biggest in its genus. In total over 30 different dragon millipedes exist, all around Southeast Asia in countries such as China and Vietnam.

Bubble-Gum Pink Elephant Hawk Moths Are Global Sensations

Both the small elephant hawk moth (Deilephila porcellus) and its larger cousin (Deilephila elpenor) rock beautiful bubblegum pink wings outlined in olive set the small elephant hawk moth (Deilephila porcellus). Both insects start out as gray, dusty-looking caterpillars that slightly resemble elephant trunks, hence the name elephant hawk moth. D. elpenor has a gorgeous pink stripe on its abdomen that differentiates it from its smaller relative.

These moths can be found in North Africa, Europe, and even as far east as China. Their location can even impact how vibrant their colors are. Moths in drier and warmer parts of Asia show less, or even an absence of, pink coloring, while moths in northwest Africa and around the Mediterranean sea have brighter colors.

Pale-Pink Naked Mole-Rats Are Resilient Feats of Nature

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/19/26/19264c01-9edd-4eb5-bdc6-51e620b39912/6257371889_6494f9e1cc_h.jpg)

As one of the most unique, and perhaps off-putting, mammals in the world, the naked mole-rat (Heterocephalus glaber) is interesting in more ways than one. They are mostly hairless, resulting in a wrinkly light-pink or gray-pink appearance. However, the practically-blind animals have whiskers on their faces and tails to sense their surroundings and hairs on their feet to help them move soil around in their East African underground environment. Naked mole-rats are also the longest-living rodents, with an estimated life expectancy of up to 30 years. They’re immune to cancer, and their risk of death doesn’t increase with old age, baffling scientists. They can even survive better than us humans, as they are able to withstand nearly 20 minutes without oxygen.

Because naked mole-rats cannot regulate their own internal temperature, they get warm using shallow tunnels and huddling together. That contact is also the most intimacy a naked mole-rat will usually get: unlike most other mammals, they are a eusocial species, meaning one queen mates with several males while the rest of the community helps raise the children. Such togetherness will quickly cease if the queen is gone, however. Several females may engage in deadly battle in order for the right to become the colony’s new leader.

This Magenta-Speckled Snake Slithers With Style

Researched for the first time in 2010, Liophidium pattoni may lack a common name, but it certainly has no shortage of pizzazz. The slithering creature is striped with hot pink speckles against black scales along its back with a bright yellow belly. The underside of the tip of its tail looks as if it was dipped in magenta, almost as if the snake is cosplaying as a mermaid, minus the fin.

The species can be found in northeast Madagascar and is just one of two kinds of snakes with bright body coloration among more than 90 species known to science on the island. Because it is not believed to be aggressive nor dangerously poisonous, its pink pattern may be an indicator of bad taste or even a bluff that it’s harmful to predators. Essentially, it could be an example of aposematic coloration without actual danger lurking behind.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3f/9c/3f9cc78c-ef72-466c-90de-f3fe5c19a713/ke2mp4.jpg)