14 Fun Facts About Sea Hawks

Number one: There’s no such thing as a “seahawk”

:focal(1739x754:1740x755)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9f/d3/9fd32eb0-fbad-404f-910b-1254e1b5ac66/ospry.jpg)

You love wildlife. You have absolutely no interest in football. Yet, due to the idiosyncrasies of American culture, you're inevitably forced to watch exactly one football game per year: the Super Bowl.

Take heart. This year's game features two teams with animal mascots. Two rather charismatic animals, in fact. We've got you covered with 14 fun facts scientists have learned about each of them. Feel free to toss them out during a lull in the game's action.

1. There's no such thing as a "seahawk."

The Seattle franchise might spell it as one word, but biologists don't. In fact, they don't even use the term to refer to one particular species.

You could use the name sea hawk to refer to an osprey (pictured above) or a skua (itself a term that covers a group of seven related species of seabirds). Both groups share a number of characteristics, including a fish-based diet.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/28/0d/280df6a3-f903-492f-b96e-afc883c81440/augur_hawk.jpg)

2. The Seattle Seahawks' "seahawk" isn't actually a sea hawk.

Before every home game, the team releases a trained bird named Taima to fly out of the tunnel before the players, lead them onto the field and get the crowd jazzed up for the game. But the nine-year-old bird is an augur hawk (also known as an augur buzzard), native to Africa, not a seafaring species that can properly be called a sea hawk.

David Knutson, the falconer who trained Taima, originally wanted an osprey for authenticity's sake, but the U.S. Fish and Wildlife service prohibited him from using a native bird for commercial purposes. Instead, he ordered an augur hawk hatchling—which has markings roughly similar to an osprey—from St. Louis' World Bird Sanctuary and trained it to deal with the noise and chaos of a raucous football game.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ce/6f/ce6f340f-55e9-4c3f-943f-66bda32aaf3f/osprey_map.jpg)

3. Ospreys live on every continent besides Antarctica.

Although they hunt over water, ospreys generally nest on land, within a few miles of either the ocean or a body of fresh water. Unlike most bird species, they are remarkably widespread, and even more surprising, nearly all these widely dispersed ospreys (with the exception of the eastern osprey, native to Australia) are part of one species.

Ospreys that live at temperate latitudes migrate to the tropics for the winter, before heading back to their home area for the summer breeding season. Other ospreys live in the tropics year-round, but also return to the specific nesting grounds (the same ones where they were born) each summer for breeding.

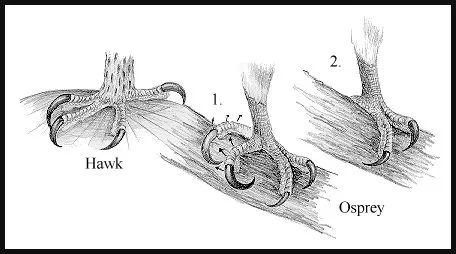

4. Ospreys have reversible toes.

Most other hawks and falcons have their talons arranged in a static pattern: three in the front, and one angled towards the back, as shown in the illustration on the left. But ospreys, like owls, have a unique configuration that lets them slide their toes back and forth, so they can create a two-and-two configuration (shown as #2). This helps them more firmly grip tubular-shaped fish as they fly through the air. They also frequently turn the fish to a position parallel to their flying direction, for aerodynamic purposes.

5. Ospreys have closable nostrils.

The predatory birds typically fly between 50 and 100 feet above the water before spotting a shallow-swimming fish (such as pike, carp or trout) and diving in for the kill. To avoid getting water up their noses, they have long-slitted nostrils that they can close voluntarily—one of the adaptations that allows them to consume a diet made up of 99 percent fish.

6. Ospreys usually mate for life.

After a male osprey reaches the age of three, upon returning to his natal nesting area for the summer breeding season in May, he stakes claim to a spot and begins performing an elaborate flight ritual overhead—often flying in a wave pattern while clutching a fish or nesting material in his talons—to attract a mate.

A female responds to his flight by landing at the nesting spot and eating the fish he supplies to her. Afterward, they begin building a nest together out of sticks, twigs, seaweed and other materials. Once bonded, the pair reunites every mating season for the rest of their lives (on average, they live about 30 years), only searching out other mates if one of the birds dies.

7. The osprey species is at least 11 million years old.

Fossils found in southern California show that ospreys were around in the Mid-Miocene, which occurred 15 to 11 million years ago. Although the particular species found have since gone extinct, they were recognizably osprey-like and assigned to their genus.

8. In the Middle Ages, people believed ospreys had magical powers.

It was widely though that if a fish looked up at an osprey, it would be somehow mesmerized by the sight of it. This would cause the fish to give itself up to the predator—a belief referenced in Act IV of Shakespeare's Coriolanus: "I think he'll be to Rome/As is the osprey to the fish, who takes it/By sovereignty of nature."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8c/50/8c50f395-5e90-4d6b-979b-25ac67555097/skua.jpg)

9. Skuas steal much of their food.

Unlike ospreys, skuas (the other birds often called "sea hawks") obtain much of their fish diet through a less noble strategy: kleptoparasitism. This means that a skua will wait until a gull, tern or other bird catches a fish, then chase after it and attack it, forcing it to eventually drop its catch so the skua can steal it. They're rather brazen in their extortion attempts—in some cases, they'll successfully steal from a bird three times their weight. During the winter, as much as 95 percent of a skua's diet can be obtained through theft.

10. Some skuas kill other birds, including penguins.

Although fish makes up the majority of their diet, some skuas use their aggressiveness to not only steal the catch away from other birds, but occasionally to kill them. South Polar skuas, in particular, are notorious for attacking penguin nesting sites, snapping up penguin chicks and eating them whole:

11. Skuas will attack anything that comes near their nests, including humans.

The birds are extremely aggressive in defending their young (perhaps from seeing firsthand what happens to less protective parents, like penguins) and will dive at the head of any animal that approaches their nest. This even applies to humans, with skuas occasionally injuring people in the act of defending their chicks.

12. Sometimes, skuas will fake injuries to distract predators.

In especially desperate situations, the birds will sometimes resort to a remarkably ingenious tactic: a distraction display, which involves an adult bird luring a predator away from a nest full of vulnerable skua chicks, generally by faking an injury. The predator (often a larger gull, hawk or eagle) follows the seemingly-debilitated skua away from the nest, intent on obtaining a larger meal, and then the skua miraculously flies away at full strength, having saved its offspring along with itself.

13. Skuas are attentive parents.

All this aggressiveness has a reasonable justification. Skuas (which mate for life, like ospreys) are attentive parents, guarding their chicks through a 57-day fledging process each year. Fathers, in particular, take on most of the responsibility, obtaining food for the chicks daily (whether by theft or honest hunting) during the entire period.

14. Some skuas migrate from the poles to the equator each year.

Among the most remarkable of all skua behaviors is the fact that pomarine skuas, which spend the summer nesting on Arctic tundra North of Russia and Canada, fly all the way down to the tropical waters off Africa and Central America each winter, a journey of several thousand miles. Next time you're judging the birds for their piratical ways, remember that they're fueling up for one of the longest journeys in the animal kingdom.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)