215-Million-Year-Old, Sharp-Nosed Sea Creature Was Among the Last of Its Kind

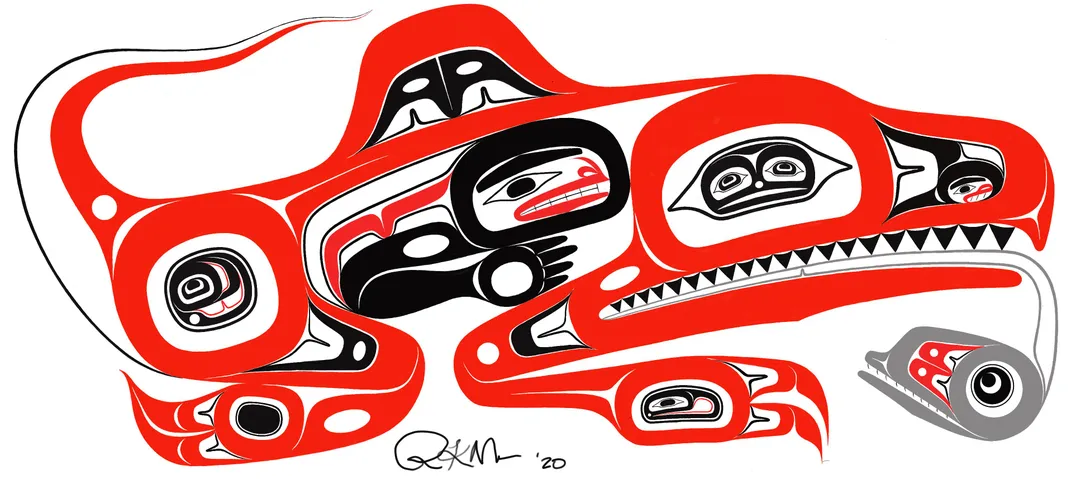

Researchers gave the marine reptile the genus name Gunakadeit in honor of a sea monster from Tlingit oral history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b6/df/b6df9cba-1962-463b-b324-e21ac8f64eed/gunakadeit-joseeae-group.jpg)

As the frigid Alaskan waters lapped at his heels, Patrick Druckenmiller repositioned his saw against the algae-dappled rock.

Pressed into the shale before the University of Alaska Fairbanks paleontologist were the fossilized remains of a brand-new species of thalattosaur, an extinct marine reptile that roamed the world’s shallow oceans during the Triassic period. If Druckenmiller and his colleagues acted quickly enough, they had a shot at giving the fossil its first taste of open air in 215 million years. But the water was rising fast—and Druckenmiller knew only hours remained before their find was once again swallowed by the sea.

“We were sawing madly,” says Druckenmiller, who was alerted to the fossil’s presence on one of the last days in 2011 when the tide was low enough to reveal the bones. “If we hadn’t gotten it that day, we might have had to wait another year.”

Armed with serrated blades and some very well-tractioned shoes, Druckenmiller’s team managed to wrest the rocks free with just minutes to spare. Sporting teeny teeth and a long, pointy snout, the odd-looking animal within would turn out to be the most complete thalattosaur skeleton described so far in North America, the researchers reported recently in the journal Scientific Reports. Dubbed Gunakadeit joseeae in honor of a sea monster described in Tlingit oral tradition, the species was also one of the last of its kind to swim the seas before thalattosaurs mysteriously died out around 200 million years ago.

“I was pretty excited to see this fossil,” says Tanja Wintrich, a marine reptile paleontologist at the University of Bonn in Germany who wasn’t involved in the study. The specimen’s age and location, she explains, make it “really rare … There’s about 20 million years of time [near the end of the Triassic] when we really don’t know what was going on.”

Initially spotted in May of 2011 by Gene Primaky, an information technology professional for the United States Forest Service in Alaska’s Tongass National Forest, the fossil was at first visible as only a neat line of vertebrae poking innocently out of a seaside outcrop. But combined with the rocks’ age and location, a photo of the bones snapped by geologist Jim Baichtal was enough for Druckenmiller to realize Primaky had probably found a thalattosaur, which immediately set off some paleontological alarm bells.

“These are animals we don’t know much about,” says Druckenmiller, who is also a curator at the University of Alaska Museum. “And Jim said, ‘we gotta come back and get this.’”

The next month, Druckenmiller returned with his colleagues to Kake, Alaska, to jailbreak the specimen, along with a few hundred pounds of the shoreline rock encasing it. Four painstaking years of fossil preparation later, a collaborator at the Tate Museum in Wyoming “had exposed one of the most beautiful, complete vertebrate skeletons ever found in Alaska,” Druckenmiller says. Based on the creature’s hodgepodge of unusual features, “it was definitely a thalattosaur. And it was definitely a new species.”

In recognition of Kake’s indigenous Tlingit people, the team approached representatives from the Sealaska Corporation and the Sealaska Heritage Institute, seeking permission to give the fossil the name Gunakadeit, a part-human sea monster who features prominently in Tlingit oral history as an ancestor of modern tribes. With approval from the elders of Kake, a council of traditional scholars “thought it was a great idea,” says Rosita Worl, an Tlingit anthropologist and president of Sealaska Heritage.

Two Tlingit values motivated the decision, Worl explains: Haa Shuká, or the responsibility to honor ancestors and future generations, and Haa Latseeni, which evokes the strength of body, mind and spirit in the face of change.

“We thought this was a good way for them to have our oral traditions reinforced … while [acknowledging] the benefits that can come from science,” she says.

Primaky then decided to commemorate his mother, Joseé, with the species name, joseeae.

Michelle Stocker, a paleontologist at Virginia Tech who wasn’t involved in the study, praised the team’s acknowledgement of the fossil’s indigenous connections. “We need to be incorporating people from the area that the fossils are from,” she says. “We can always do a better job listening.”

Like other thalattosaurs—the descendants of a lineage of reptiles that once lived on land before returning to the ocean—the three-foot-long Gunakadeit was a full-time denizen of the world’s coastal waters, Druckenmiller says. But its bizarrely shaped snout, which tapered into a thin-tipped point, clearly set this species apart from its kin. Though other thalattosaurs are known to boast thick, shell-crushing chompers or blade-like incisors for slicing through flesh, the Gunakadeit fossil harbored only a smattering of small, cone-shaped teeth on the back half of its lower jaw.

Gunakadeit’s feeding habits can’t be confirmed without a time machine. But Druckenmiller suspects it was probably poking its spindly schnoz into cracks and crevices, rooting for soft-bodied prey that it could snatch with its teeth and suck down like a vacuum. The lack of foreign bones in the creature’s guts seems to bolster the case for a squishy diet—though Stocker points out that this particular specimen may have simply missed out on a recent meal.

While good for rooting out coral-dwelling prey, thalattosaurs’ hard-nosed affinity for shallow waters may have also been their undoing. Toward the end of the Triassic—not long after the team’s specimen met its own tragic end—sea levels plummeted, culling a large portion of Earth’s coral reefs. While other marine reptiles such as porpoise-like ichthyosaurs and long-necked plesiosaurs had the evolutionary flexibility to expand into deeper ocean environments, hyper-specialized thalattosaurs like Gunakadeit may have struggled to follow suit.

To truly test that theory, more fossils are needed, says Lene Liebe Delsett, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Oslo who wasn’t involved in the study. Researchers still aren’t even sure exactly when or where thalattosaurs died out—or how the group’s scant survivors managed to eke out a living before they finally disappeared.

“So much new data has come out in the last 10 or 15 years,” Delsett says. “But there are still a lot of questions we don’t have the answers to.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)