3-D Printed Sea Turtle Eggs Reveal Poaching Routes

Scientists put GPS locators inside plastic eggs to find trafficking destinations in Costa Rica

:focal(2771x2200:2772x2201)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fb/6f/fb6f27b8-e470-44e8-825a-70bb88a97448/gettyimages-1199222400.jpg)

Biologist Helen Pheasey knew that on a typical night it would take a sea turtle around twenty minutes to lay her eggs, which gave the scientist plenty of time to sneak one extra, very special egg into the reptile’s nest. Pheasey was also aware that poachers would likely arrive that night or the next to swipe sea turtle eggs, which are rumored to have aphrodisiac qualities and are sold on the black market as food. But Pheasey’s egg wasn’t going to be anyone’s snack: it was a plastic copycat that had a tracker hidden inside.

She and her team were the first to use the covert tracking device, called the InvestEGGator, in an effort to reveal illegal trade networks and better understand what drives sea turtle egg poaching. The scientists deployed around a hundred of the fake eggs in sea turtle nests across four beaches in Costa Rica and waited. Each egg contained a GPS transmitter set to ping cell towers every hour, which would allow scientists to follow the InvestEGGator eggs on a smartphone app.

“It was really a case of seeing, well, what're the challenges when you actually start putting them into turtle nests?” says Pheasey. “Will it work?”

In a study published this week in Current Biology, Pheasey and her team showed that the trackers did work. Five of the deployed eggs were taken by unsuspecting poachers. The shortest route was roughly a mile, but one InvestEGGator traveled more than 80 miles, capturing what researchers were hoping for: the complete trade route, from the beach to the buyer. “Having that moment where the trade chain was complete....that was obviously a very big moment,” says Pheasey.

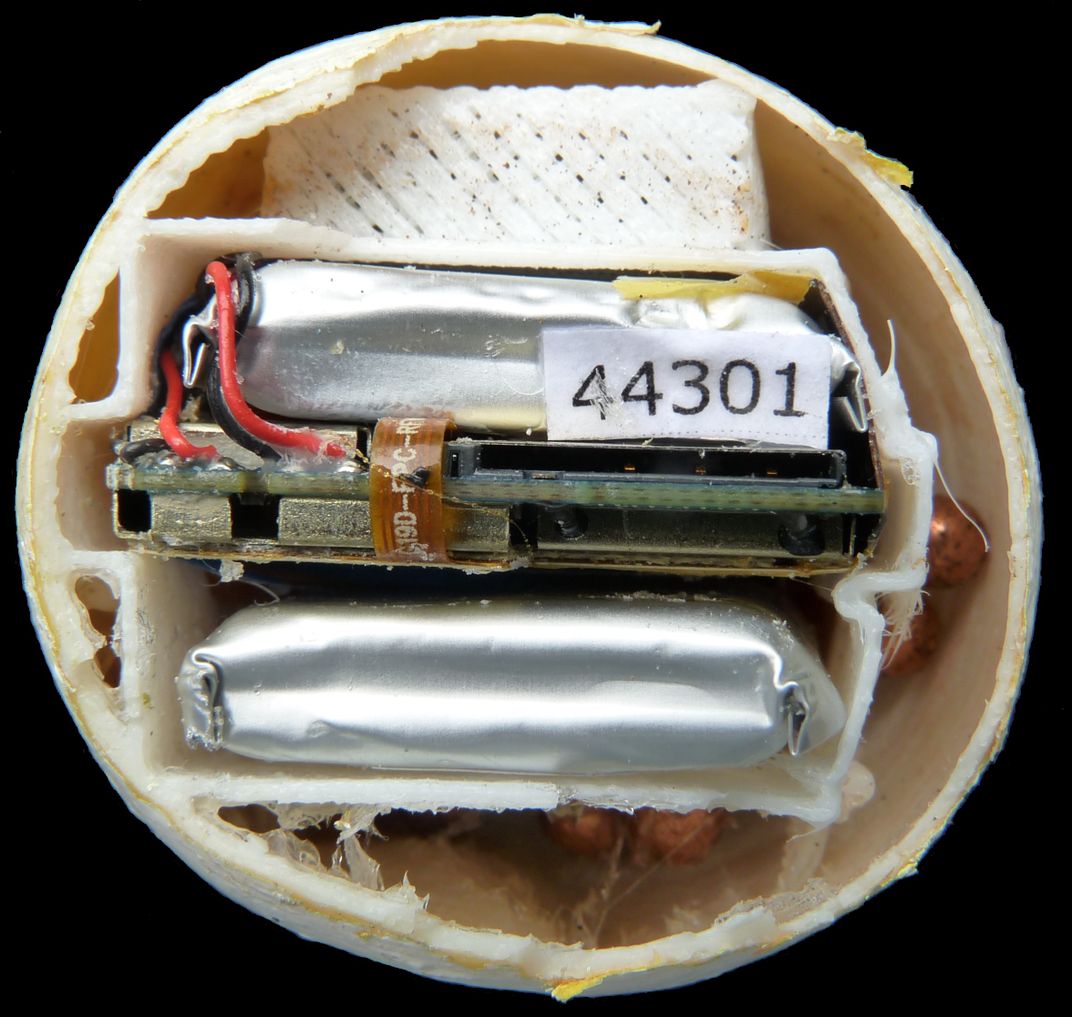

The InvestEGGator was the invention of Kim Williams-Guillén, a conservation scientist at Paso Pacífico who conceived the idea as part of the Wildlife Crime Tech Challenge in 2015. The trick, says Williams-Guillén, was designing a device that looked and felt like a sea turtle egg while being precise enough to reveal trade routes. Sea turtle eggs are the size of ping pong balls, but unlike brittle chicken eggs, their shell is leathery and pliable. “Making [the trackers] look like eggs from far away was not going to be an issue, it was more making them feel like turtle eggs,” says Williams-Guillén. “One of the ways that [poachers] know that a turtle egg is good when they're sorting their eggs is that it's still soft and squishy.”

To capture the right feel, Williams-Guillén’s 3-D printed a shell out of a plastic material called NinjaFlex. She even incorporated a dimple into the shell’s design, a characteristic of young, healthy sea turtle eggs.

“Once [the fake eggs] are covered in the mucus that comes from the nesting process and the sand is covering them, it's very, very hard to distinguish between one or the other,” she says. It also helps that poachers usually work quickly, and in the dark.

To place the decoy eggs, scientists waited for nesting females, who lay clutches of around a hundred eggs at night. It’s fortunate that sea turtles are slow-moving creatures that remain largely aloof to the presence of scientists, says Pheasey, but it’s also what makes them an easy target for poachers.

Her team placed InvestEGGators in 101 different nests of both green sea turtles and olive ridley sea turtles across Costa Rica. Most eggs went unpoached, and the trackers were later retrieved by scientists. Of the nests containing decoy eggs, a quarter were illegally harvested. Some of the eggs failed to connect to a GPS signal, while other eggs were spotted by poachers and tossed aside. Five of those poached eggs gave the team useful tracking data.

The five eggs’ signals were accurate to around ten meters in areas with many cell towers, which Pheasey says “isn't bad for something that fits inside a ping pong ball.”

Two of the InvestEGGators moved slightly more than a mile, to local bars or private residences. The longest voyage was around 85 miles, which Pheasey recalls watching on her phone over the course of two days. “It just kept moving,” she says. First, Pheasey saw the egg stop behind a grocery store. The next day the egg moved inland to a private residence, which Pheasey thinks was its final destination.

This illegal trade network revealed that eggs are sold and consumed locally, something Pheasey says they suspected based on anecdotal evidence. The routes they discovered also suggest that most egg poachers in the area are individuals looking to make quick money, not an organized network.

The poachers who picked up InvestEGGators will never be prosecuted. “The aim of these decoys isn't to penalize those people,” says Pheasey. “What we're more interested in is, okay, what patterns do we get from this?”

For example, if eggs are being poached and eaten in the same small town, conservationists know where to spend time and energy with education and support.

By using tools like the InvestEGGator, scientists are “able to remote sense in ways we couldn't have even thought of 30 years ago,” says Roderic Mast, president of Oceanic Society and co-chairman of the IUCN Marine Turtle Specialist Group. “If you had wanted to do what those little awesome egg trackers do now, you would have had to hide behind a bush and see the guy dig the eggs up and then follow him back home,” says Mast. “It's very cool.”

Finding these routes matters for sea turtle conservation, he says. “If you can better understand the business of egg collection and distribution in the country, then you can better enforce the laws.”

All seven sea turtle species are suffering on a global scale and the demand of sea turtle eggs is only a piece of the puzzle. Climate change, pollution, habitat loss and bycatch are serious threats, too. The two species Pheasey tracked, green sea turtles and olive ridley sea turtles, are classified as endangered and vulnerable, respectively.

Protecting hatchings is particularly important because sea turtles return to nest on the same beach where they are born, says Roldán Valverde, a biologist at Southeastern Louisiana University and scientific director of the Sea Turtle Conservancy, who was not involved in the work. “Over time, what you're going to do is you're going to deplete that beach of sea turtles altogether,” he says.

The technology has the power, he says, to expose trade routes that could help scientists better understand what drives egg poaching. “Over time, it's going to give the authorities enough information to do something about it,” he says. But to make a meaningful difference in deterring poaching, Valverde says his home country of Costa Rica would need “a very strong coordinated effort.”

The decoy eggs “provide some knowledge about aspects of the market that can't always be elucidated by just asking around or making observations,” says Williams-Guillén. Alone, it won’t be enough to save sea turtles from extinction, she says, but “it's another blade on your Swiss Army knife.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/corryn.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/corryn.png)