If you find yourself tired of streaming services, reading the news or video-chatting with friends, maybe you should consider becoming a citizen scientist. Though it’s true that many field research projects are paused, hundreds of scientists need your help sifting through wildlife camera footage and images of galaxies far, far away, or reading through diaries and field notes from the past.

Plenty of these tools are free and easy enough for children to use. You can look around for projects yourself on Smithsonian Institution’s citizen science volunteer page, National Geographic’s list of projects and CitizenScience.gov’s catalog of options. Zooniverse is a platform for online-exclusive projects, and Scistarter allows you to restrict your search with parameters, including projects you can do “on a walk,” “at night” or “on a lunch break.”

To save you some time, Smithsonian magazine has compiled a collection of dozens of projects you can take part in from home.

American Wildlife

If being home has given you more time to look at wildlife in your own backyard, whether you live in the city or the country, consider expanding your view, by helping scientists identify creatures photographed by camera traps. Improved battery life, motion sensors, high-resolution and small lenses have made camera traps indispensable tools for conservation.These cameras capture thousands of images that provide researchers with more data about ecosystems than ever before.

Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute’s eMammal platform, for example, asks users to identify animals for conservation projects around the country. Currently, eMammal is being used by the Woodland Park Zoo’s Seattle Urban Carnivore Project, which studies how coyotes, foxes, raccoons, bobcats and other animals coexist with people, and the Washington Wolverine Project, an effort to monitor wolverines in the face of climate change. Identify urban wildlife for the Chicago Wildlife Watch, or contribute to wilderness projects documenting North American biodiversity with The Wilds' Wildlife Watch in Ohio, Cedar Creek: Eyes on the Wild in Minnesota, Michigan ZoomIN, Western Montana Wildlife and Snapshot Wisconsin.

"Spend your time at home virtually exploring the Minnesota backwoods,” writes the lead researcher of the Cedar Creek: Eyes on the Wild project. “Help us understand deer dynamics, possum populations, bear behavior, and keep your eyes peeled for elusive wolves!"

On Safari

If being cooped up at home has you daydreaming about traveling, Snapshot Safari has six active animal identification projects. Try eyeing lions, leopards, cheetahs, wild dogs, elephants, giraffes, baobab trees and over 400 bird species from camera trap photos taken in South African nature reserves, including De Hoop Nature Reserve and Madikwe Game Reserve.

With South Sudan DiversityCam, researchers are using camera traps to study biodiversity in the dense tropical forests of southwestern South Sudan. Part of the Serenegeti Lion Project, Snapshot Serengeti needs the help of citizen scientists to classify millions of camera trap images of species traveling with the wildebeest migration.

Classify all kinds of monkeys with Chimp&See. Count, identify and track giraffes in northern Kenya. Watering holes host all kinds of wildlife, but that makes the locales hotspots for parasite transmission; Parasite Safari needs volunteers to help figure out which animals come in contact with each other and during what time of year.

Mount Taranaki in New Zealand is a volcanic peak rich in native vegetation, but native wildlife, like the North Island brown kiwi, whio/blue duck and seabirds, are now rare—driven out by introduced predators like wild goats, weasels, stoats, possums and rats. Estimate predator species compared to native wildlife with Taranaki Mounga by spotting species on camera trap images.

The Zoological Society of London’s (ZSL) Instant Wild app has a dozen projects showcasing live images and videos of wildlife around the world. Look for bears, wolves and lynx in Croatia; wildcats in Costa Rica’s Osa Peninsula; otters in Hampshire, England; and both black and white rhinos in the Lewa-Borana landscape in Kenya.

Under the Sea

Researchers use a variety of technologies to learn about marine life and inform conservation efforts. Take, for example, Beluga Bits, a research project focused on determining the sex, age and pod size of beluga whales visiting the Churchill River in northern Manitoba, Canada. With a bit of training, volunteers can learn how to differentiate between a calf, a subadult (grey) or an adult (white)—and even identify individuals using scars or unique pigmentation—in underwater videos and images. Beluga Bits uses a “beluga boat,” which travels around the Churchill River estuary with a camera underneath it, to capture the footage and collect GPS data about the whales’ locations.

Many of these online projects are visual, but Manatee Chat needs citizen scientists who can train their ear to decipher manatee vocalizations. Researchers are hoping to learn what calls the marine mammals make and when—with enough practice you might even be able to recognize the distinct calls of individual animals.

Several groups are using drone footage to monitor seal populations. Seals spend most of their time in the water, but come ashore to breed. One group, Seal Watch, is analyzing time-lapse photography and drone images of seals in the British territory of South Georgia in the South Atlantic. A team in Antarctica captured images of Weddell seals every ten minutes while the seals were on land in spring to have their pups. The Weddell Seal Count project aims to find out what threats—like fishing and climate change—the seals face by monitoring changes in their population size. Likewise, the Año Nuevo Island - Animal Count asks volunteers to count elephant seals, sea lions, cormorants and more species on a remote research island off the coast of California.

With Floating Forests, you’ll sift through 40 years of satellite images of the ocean surface identifying kelp forests, which are foundational for marine ecosystems, providing shelter for shrimp, fish and sea urchins. A project based in southwest England, Seagrass Explorer, is investigating the decline of seagrass beds. Researchers are using baited cameras to spot commercial fish in these habitats as well as looking out for algae to study the health of these threatened ecosystems. Search for large sponges, starfish and cold-water corals on the deep seafloor in Sweden’s first marine park with the Koster seafloor observatory project.

The Smithsonian Environmental Research Center needs your help spotting invasive species with Invader ID. Train your eye to spot groups of organisms, known as fouling communities, that live under docks and ship hulls, in an effort to clean up marine ecosystems.

If art history is more your speed, two Dutch art museums need volunteers to start “fishing in the past” by analyzing a collection of paintings dating from 1500 to 1700. Each painting features at least one fish, and an interdisciplinary research team of biologists and art historians wants you to identify the species of fish to make a clearer picture of the “role of ichthyology in the past.”

Interesting Insects

Notes from Nature is a digitization effort to make the vast resources in museums’ archives of plants and insects more accessible. Similarly, page through the University of California Berkeley’s butterfly collection on CalBug to help researchers classify these beautiful critters. The University of Michigan Museum of Zoology has already digitized about 300,000 records, but their collection exceeds 4 million bugs. You can hop in now and transcribe their grasshopper archives from the last century. Parasitic arthropods, like mosquitos and ticks, are known disease vectors; to better locate these critters, the Terrestrial Parasite Tracker project is working with 22 collections and institutions to digitize over 1.2 million specimens—and they’re 95 percent done. If you can tolerate mosquito buzzing for a prolonged period of time, the HumBug project needs volunteers to train its algorithm and develop real-time mosquito detection using acoustic monitoring devices. It’s for the greater good!

For the Birders

Birdwatching is one of the most common forms of citizen science. Seeing birds in the wilderness is certainly awe-inspiring, but you can birdwatch from your backyard or while walking down the sidewalk in big cities, too. With Cornell University’s eBird app, you can contribute to bird science at any time, anywhere. (Just be sure to remain a safe distance from wildlife—and other humans, while we social distance). If you have safe access to outdoor space—a backyard, perhaps—Cornell also has a NestWatch program for people to report observations of bird nests. Smithsonian’s Migratory Bird Center has a similar Neighborhood Nest Watch program as well.

Birdwatching is easy enough to do from any window, if you’re sheltering at home, but in case you lack a clear view, consider these online-only projects. Nest Quest currently has a robin database that needs volunteer transcribers to digitize their nest record cards.

You can also pitch in on a variety of efforts to categorize wildlife camera images of burrowing owls, pelicans, penguins (new data coming soon!), and sea birds. Watch nest cam footage of the northern bald ibis or greylag geese on NestCams to help researchers learn about breeding behavior.

Or record the coloration of gorgeous feathers across bird species for researchers at London’s Natural History Museum with Project Plumage.

Pretty Plants

If you’re out on a walk wondering what kind of plants are around you, consider downloading Leafsnap, an electronic field guide app developed by Columbia University, the University of Maryland and the Smithsonian Institution. The app has several functions. First, it can be used to identify plants with its visual recognition software. Secondly, scientists can learn about the “the ebb and flow of flora” from geotagged images taken by app users.

What is older than the dinosaurs, survived three mass extinctions and still has a living relative today? Ginko trees! Researchers at Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History are studying ginko trees and fossils to understand millions of years of plant evolution and climate change with the Fossil Atmospheres project. Using Zooniverse, volunteers will be trained to identify and count stomata, which are holes on a leaf’s surface where carbon dioxide passes through. By counting these holes, or quantifying the stomatal index, scientists can learn how the plants adapted to changing levels of carbon dioxide. These results will inform a field experiment conducted on living trees in which a scientist is adjusting the level of carbon dioxide for different groups.

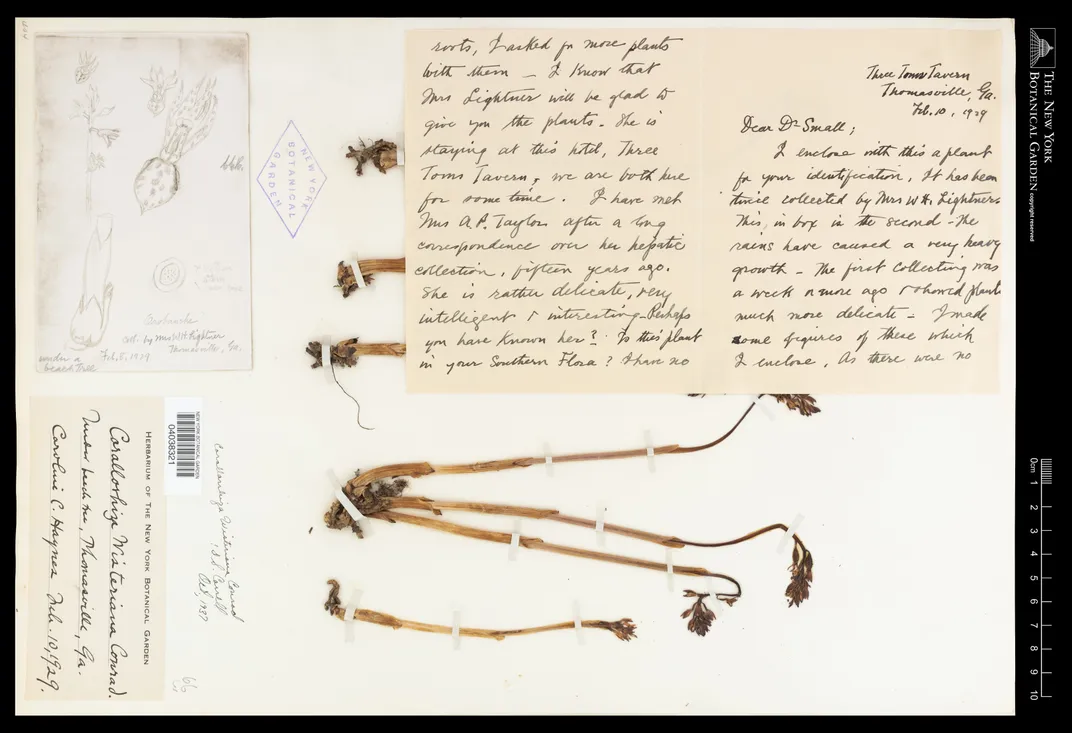

Help digitize and categorize millions of botanical specimens from natural history museums, research institutions and herbaria across the country with the Notes from Nature Project. Did you know North America is home to a variety of beautiful orchid species? Lend botanists a handby typing handwritten labels on pressed specimens or recording their geographic and historic origins for the New York Botanical Garden’s archives. Likewise, the Southeastern U.S. Biodiversity project needs assistance labeling pressed poppies, sedums, valerians, violets and more. Groups in California, Arkansas, Florida, Texas and Oklahoma all invite citizen scientists to partake in similar tasks.

Historic Women in Astronomy

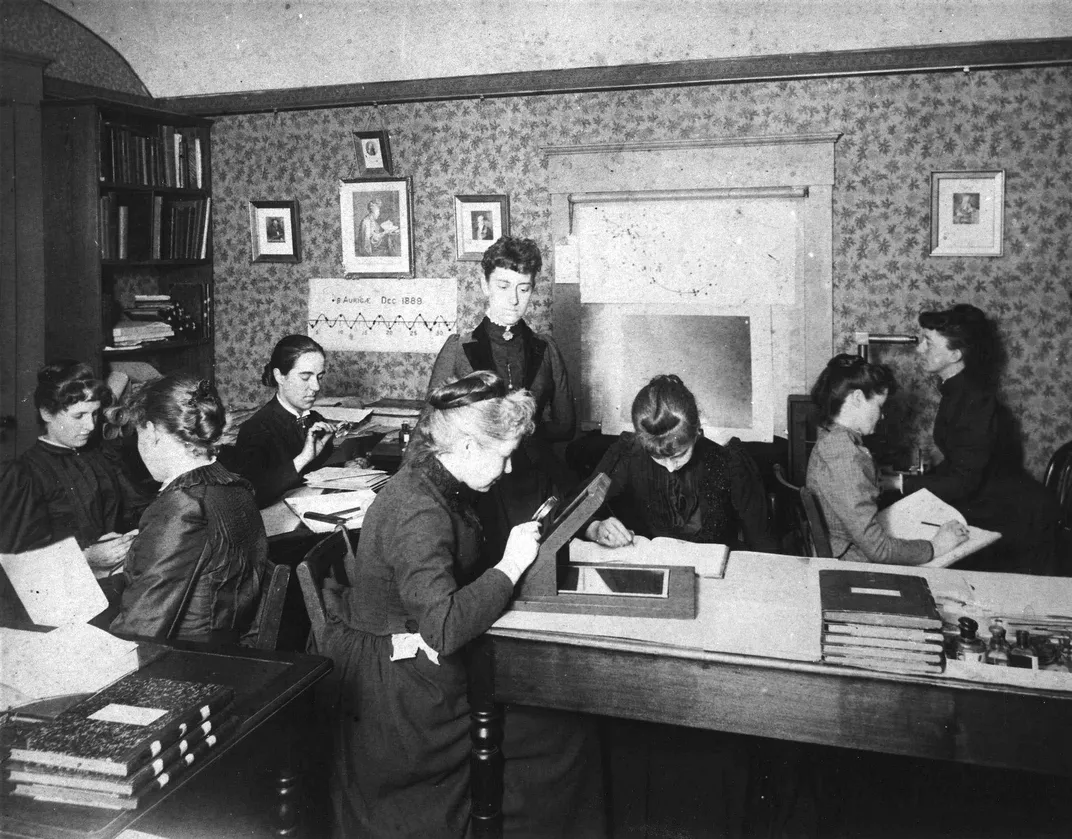

Become a transcriber for Project PHaEDRA and help researchers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics preserve the work of Harvard’s women “computers” who revolutionized astronomy in the 20th century. These women contributed more than 130 years of work documenting the night sky, cataloging stars, interpreting stellar spectra, counting galaxies, and measuring distances in space, according to the project description.

More than 2,500 notebooks need transcription on Project PhaEDRA - Star Notes. You could start with Annie Jump Cannon, for example. In 1901, Cannon designed a stellar classification system that astronomers still use today. Cecilia Payne discovered that stars are made primarily of hydrogen and helium and can be categorized by temperature. Two notebooks from Henrietta Swan Leavitt are currently in need of transcription. Leavitt, who was deaf, discovered the link between period and luminosity in Cepheid variables, or pulsating stars, which “led directly to the discovery that the Universe is expanding,” according to her bio on Star Notes.

Volunteers are also needed to transcribe some of these women computers’ notebooks that contain references to photographic glass plates. These plates were used to study space from the 1880s to the 1990s. For example, in 1890, Williamina Flemming discovered the Horsehead Nebula on one of these plates. With Star Notes, you can help bridge the gap between “modern scientific literature and 100 years of astronomical observations,” according to the project description. Star Notes also features the work of Cannon, Leavitt and Dorrit Hoffleit, who authored the fifth edition of the Bright Star Catalog, which features 9,110 of the brightest stars in the sky.

Microscopic Musings

Electron microscopes have super-high resolution and magnification powers—and now, many can process images automatically, allowing teams to collect an immense amount of data. Francis Crick Institute’s Etch A Cell - Powerhouse Hunt project trains volunteers to spot and trace each cell’s mitochondria, a process called manual segmentation. Manual segmentation is a major bottleneck to completing biological research because using computer systems to complete the work is still fraught with errors and, without enough volunteers, doing this work takes a really long time.

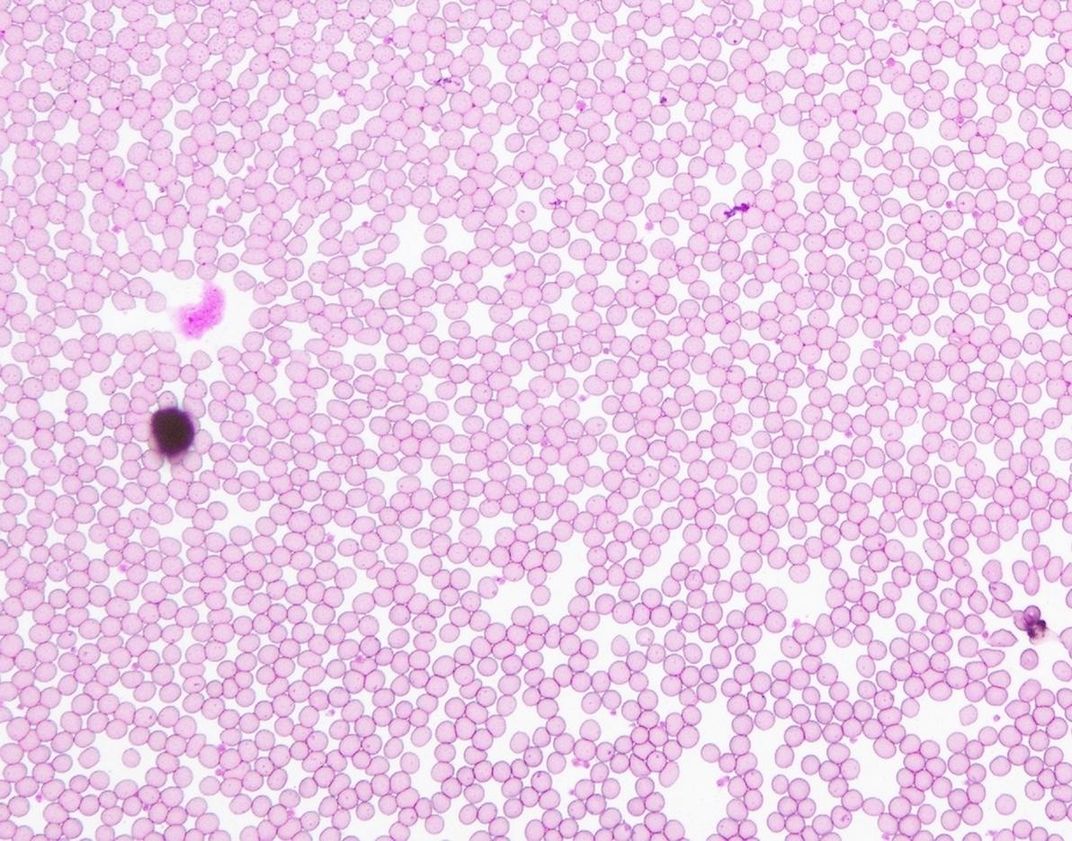

For the Monkey Health Explorer project, researchers studying the social behavior of rhesus monkeys on the tiny island Cayo Santiago off the southeastern coast of Puerto Rico need volunteers to analyze the monkeys’ blood samples. Doing so will help the team understand which monkeys are sick and which are healthy, and how the animals’ health influences behavioral changes.

Using the Zooniverse’s app on a phone or tablet, you can become a “Science Scribbler” and assist researchers studying how Huntington disease may change a cell’s organelles. The team at the United Kingdom's national synchrotron, which is essentially a giant microscope that harnesses the power of electrons, has taken highly detailed X-ray images of the cells of Huntington’s patients and needs help identifying organelles, in an effort to see how the disease changes their structure.

Oxford University’s Comprehensive Resistance Prediction for Tuberculosis: an International Consortium—or CRyPTIC Project, for short, is seeking the aid of citizen scientists to study over 20,000 TB infection samples from around the world. CRyPTIC’s citizen science platform is called Bash the Bug. On the platform, volunteers will be trained to evaluate the effectiveness of antibiotics on a given sample. Each evaluation will be checked by a scientist for accuracy and then used to train a computer program, which may one day make this process much faster and less labor intensive.

Out of This World

If you’re interested in contributing to astronomy research from the comfort and safety of your sidewalk or backyard, check out Globe at Night. The project monitors light pollution by asking users to try spotting constellations in the night sky at designated times of the year. (For example, Northern Hemisphere dwellers should look for the Bootes and Hercules constellations from June 13 through June 22 and record the visibility in Globe at Night’s app or desktop report page.)

For the amateur astrophysicists out there, the opportunities to contribute to science are vast. NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) mission is asking for volunteers to search for new objects at the edges of our solar system with the Backyard Worlds: Planet 9 project.

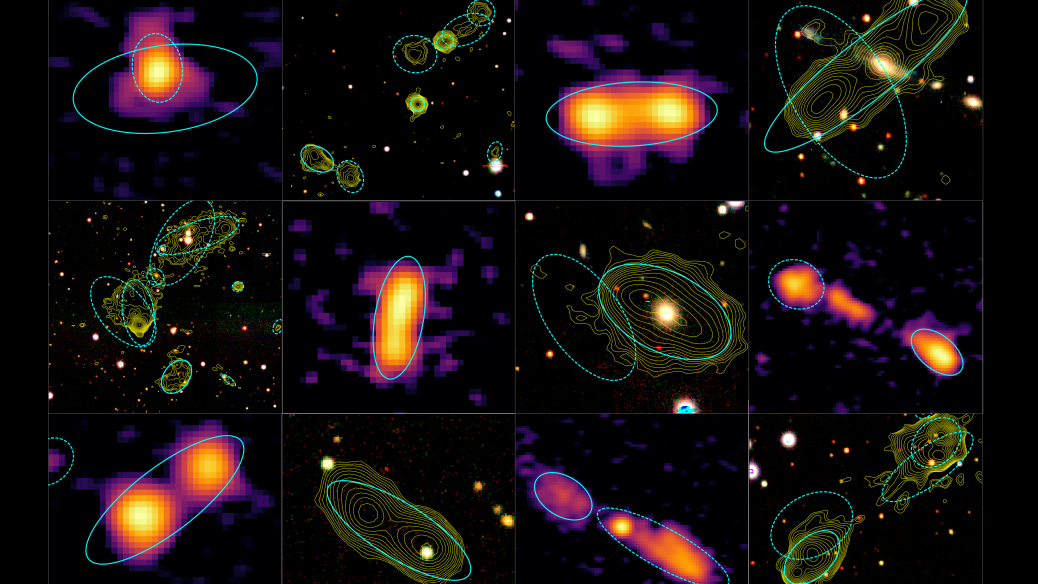

Galaxy Zoo on Zooniverse and its mobile app has operated online citizen science projects for the past decade. According to the project description, there are roughly one hundred billion galaxies in the observable universe. Surprisingly, identifying different types of galaxies by their shape is rather easy. “If you're quick, you may even be the first person to see the galaxies you're asked to classify,” the team writes.

With Radio Galaxy Zoo: LOFAR, volunteers can help identify supermassive blackholes and star-forming galaxies. Galaxy Zoo: Clump Scout asks users to look for young, “clumpy” looking galaxies, which help astronomers understand galaxy evolution.

If current events on Earth have you looking to Mars, perhaps you’d be interested in checking out Planet Four and Planet Four: Terrains—both of which task users with searching and categorizing landscape formations on Mars’ southern hemisphere. You’ll scroll through images of the Martian surface looking for terrain types informally called “spiders,” “baby spiders,” “channel networks” and “swiss cheese.”

Gravitational waves are telltale ripples in spacetime, but they are notoriously difficult to measure. With Gravity Spy, citizen scientists sift through data from Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO, detectors. When lasers beamed down 2.5-mile-long “arms” at these facilities in Livingston, Louisiana and Hanford, Washington are interrupted, a gravitational wave is detected. But the detectors are sensitive to “glitches” that, in models, look similar to the astrophysical signals scientists are looking for. Gravity Spy teaches citizen scientists how to identify fakes so researchers can get a better view of the real deal. This work will, in turn, train computer algorithms to do the same.

Similarly, the project Supernova Hunters needs volunteers to clear out the “bogus detections of supernovae,” allowing researchers to track the progression of actual supernovae. In Hubble Space Telescope images, you can search for asteroid tails with Hubble Asteroid Hunter. And with Planet Hunters TESS, which teaches users to identify planetary formations, you just “might be the first person to discover a planet around a nearby star in the Milky Way,” according to the project description.

Help astronomers refine prediction models for solar storms, which kick up dust that impacts spacecraft orbiting the sun, with Solar Stormwatch II. Thanks to the first iteration of the project, astronomers were able to publish seven papers with their findings.

With Mapping Historic Skies, identify constellations on gorgeous celestial maps of the sky covering a span of 600 years from the Adler Planetarium collection in Chicago. Similarly, help fill in the gaps of historic astronomy with Astronomy Rewind, a project that aims to “make a holistic map of images of the sky.”

:focal(300x157:301x158)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e2/ca/e2ca665f-77b7-4ba2-8cd2-46f38cbf2b60/citizen_science_mobile.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d4/d7/d4d7ecc4-0605-497c-a585-6916c8d655a0/citizen_science.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rachael.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rachael.png)