A Buddhist Monk Saves One of the World’s Rarest Birds

High in the Himalayas, the Tibetan bunting is getting help from a very special friend

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Phenom-Tibetan-bunting-631.jpg)

“Rrrrrr, Badgers!” Tashi Zangpo says, cradling the remains of a bird nest in his hands on a mountain slope nearly 14,000 feet above sea level. For weeks, Tashi, a Tibetan Buddhist monk and self-taught conservation biologist, has scoured these mountains in China’s Qinghai province for nests of the Tibetan bunting. Now that he’s found one, he’s discovered that a badger has beaten him to it and devoured the young.

The Tibetan bunting (Emberiza koslowi) is one of the least-known birds on the planet. It has a black and white head and chestnut-colored back and is only slightly larger than a chickadee. In 1900, Russian explorers were the first to document the bird and collect specimens. One hundred years later, British ornithologists published only the third scientific study of the bunting, based on fewer than four hours of observations.

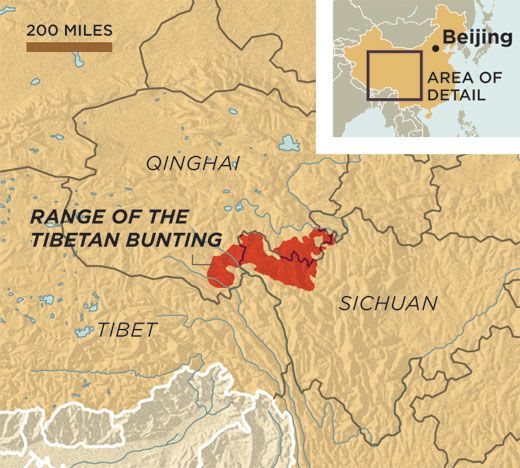

The bird’s obscurity is due in large part to the remoteness of its habitat. In A Field Guide to the Birds of China, the bunting’s home range appears as a tiny splotch on the eastern edge of the Tibetan plateau. The bird lives in a region of rugged peaks and isolated valleys where four of Asia’s largest rivers—the Yellow, the Yangtze, the Mekong and the Salween—tumble down snowcapped mountains before spreading across the continent.

Tibetans, an ethnic group that predominates here, call it the “dzi bead bird” because the stripes on its head resemble the agate amulets locals wear to ward off evil spirits. Tashi and his friends have tracked the birds closely for the past eight years. They now know that buntings descend 2,000 feet downslope into warmer, more protected valleys in November and stay there until May. They know how the birds’ diet changes throughout the year: In winter buntings forage on oats and other grains; in summer they eat butterflies, grasshoppers, beetles and other insects. The monks have found that the birds lay an average of 3.6 eggs per nest, and that their main predators are falcons, owls, fox and weasels, in addition to badgers. “When we started in 2003, we started looking in trees for the nests,” Tashi says of the ground-nesting buntings. “We didn’t know anything.”

Tashi saw his first Tibetan bunting as a young monk in Baiyu, a village in Qinghai province not far from where he and I now stand. One of eight children, he came to the monastery at age 13 when his parents could no longer afford to take care of him. He was homesick and often hiked up a mountain above the village to surround himself with songbirds he knew from home. Using a sharp rock, he etched images of the birds on fieldstones. An older lama at the monastery noticed his interest and taught him how to make paper so he could draw the birds.

Tashi, now 41, has since crisscrossed the Tibetan plateau, drawing 400 bird species. He is currently compiling a field guide that evokes the work of John James Audubon or Roger Tory Peterson. He wears prayer beads on one wrist and a digital watch with altimeter and compass on the other. “Friends of mine joke with me saying, ‘That person is a reincarnation of a lama, that person is a reincarnation of a rinpoche [a great teacher] and you, you are a reincarnation of a sparrow,’” he says.

Tashi has noticed dramatic changes in the environment, including shrinking glaciers, increasing human development and declining bird populations. Based on his own observations and on ancient Tibetan scripts about wild plants and animals, Tashi says the buntings, never high in number, are among the most vulnerable of all Tibetan birds. Yak herding increases every year, and the animals trample the buntings’ nests. Climate change is causing nearby glaciers to disappear and meadows to go dry, forcing birds and livestock to share an ever-shrinking area.

By explaining his findings to local herders, Tashi was able to get critical bunting habitat protected for the July through September nesting season. “We’ve told the herders these months are for the Tibetan buntings to use,” he says. “Once the birds fledge, then the yaks can eat here.” In one valley where grazing is now restricted, bunting numbers increased from about 5 in 2005 to 29 in 2009.

Tashi has been improving his field biology skills with help from Wang Fang, a conservation biology graduate student at Peking University in Beijing. Rather than wandering alone across a mountainside to count birds in a given area, the monk now walks defined paths flanked at 110-yard intervals by other observers. He uses GPS equipment to map the bird’s distribution and is compiling his findings for publication in an academic journal. Based on sightings and the amount of suitable habitat, Tashi believes the bird’s range is even smaller than what is shown in existing field guides.

When it comes to protecting the species, Wang says that Tashi is already accomplishing more on his own than Wang could ever hope to. “If you are a scientist, you can’t go to Tashi’s village and say Buddha doesn’t like you to do this or that. But he can, and they will listen to him.”

I first met Tashi at a scientific conference in Beijing. A Chinese conservation organization had invited him to speak to provide an example of the grass-roots efforts they support. Tashi is just one of countless amateur biologists around the world, but he possesses a rare combination of passion and talent.

“He is a good scientist who at the same time is doing conservation and environmental education,” says George Schaller, one of the world’s pre-eminent conservation biologists (see “The Jaguar Freeway,” p. 48). Tashi recently started assisting Schaller, of Panthera, a big cat conservation organization, by monitoring snow leopards and blue sheep in the mountains around Baiyu. Schaller says the monk’s greatest contribution to conservation, however, may be his field guide of the region’s birds in the local language. “He is an exceptional artist, like the talented, old-fashioned naturalists of Britain and North America, who brings to his work a deep Buddhist reverence for all life. It’s a wonderful combination.” Tashi’s field guide “will be a tremendous benefit to the Tibetan culture,” Schaller says.

Four years ago, Tashi and Druk Kyab, another monk in the monastery in Baiyu, formed the Nyanpo Yutse Environmental Protection Association, named after a nearby mountain considered sacred by local Tibetans. The group, consisting of five full-time staff members and about 60 volunteers, has taken it upon itself to preserve the region’s plants, animals, lakes and streams. Most of the work has focused on the Tibetan bunting, but the group has also compiled detailed notes on dozens of other species, as well as the rate at which nearby glaciers are receding.

One of the remaining mysteries Tashi and Wang are trying to solve is why the buntings have such poor breeding success. Even in areas where summer grazing has ceased, fewer than 30 percent of chicks survive. Predators and flooding are the top causes of mortality, but it’s not clear why these problems afflict Tibetan buntings more than other bird species that nest on the ground.

On the mountain slope, Tashi discovers there may still be hope for at least one of this year’s young. A short distance from where he found the ravaged nest, he spies a chick, still too young to fly, hopping through the grass. The bird somehow escaped the badger attack and is likely the sole survivor from this year’s brood.

The bird’s parents have seen it as well. As Tashi and Druk watch, the adults feed it grasshoppers and other delicacies. It won’t be able to fly for a few more days and predators are still a risk. “Tonight we’ll say a prayer for this chick that it can grow up to be big and strong, and go to college,” Tashi says with a smile.

We descend into a valley for the night and head back up the mountain the following morning. The bunting parents have continued to feed the chick. The young bird can hop farther now than the day before, and the monks are confident it will soon fly.

Returning to Baiyu that afternoon, Tashi and Druk stop by the monastery, where a group of young monks crowd around them. Tashi tells them about the badger that ate all but one of the chicks and how the Nyanpo Yutse group helps protect the birds.

“As Buddhists, this is something we have to do—we have to help protect the birds and animals that don’t have any other protection,” he tells the youngsters.

Then he tells them that he’ll be going back up the mountain soon. He asks who would like to join him. A roomful of hands shoot up from beneath crimson robes. “Me!” the children shout.

Phil McKenna taught English in China; he writes about energy and the environment.