A Close Encounter With the Rarest Bird

Newfound negatives provide fresh views of the young ivory-billed woodpecker

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Indelible-ivory-billed-woodpecker-631.jpg)

The ivory-billed woodpecker is one of the most extraordinary birds ever to live in America’s forests: the biggest woodpecker in the United States, it seems to keep coming back from the dead. Once resident in swampy bottomlands from North Carolina to East Texas, it was believed to have gone extinct as early as the 1920s, but sightings, confirmed and otherwise, have been reported as recently as this year.

The young ornithologist James T. Tanner’s sightings in the late 1930s came with substantial documentation: not only field notes, from which he literally wrote the book on the species, but also photographs. In fact, Tanner’s photographs remain the most recent uncontested pictures of the American ivory-bill. Now his widow, Nancy Tanner, has discovered more photographs that he took on a fateful day in 1938.

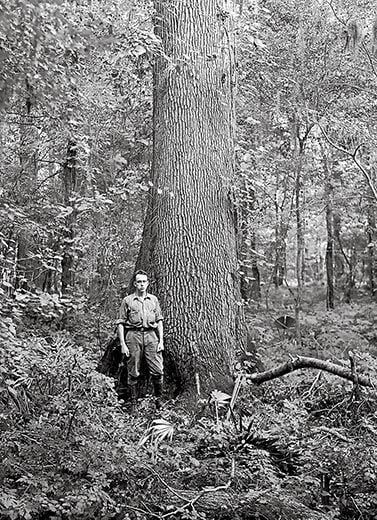

Tanner was a doctoral candidate at Cornell University when, in 1937, he was sent to look for ivory-bills in Southern swamplands, including a vast virgin forest in northeast Louisiana called the Singer Tract. Two years earlier, his mentor, Arthur Allen, founder of the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, had proved that the “Lord God” bird—so named for what people supposedly exclaimed after getting a look at its 20-inch body and 30-inch wingspan—was still extant, with observations of several adult ivory-bills in the same forest.

“There are relatively few references to young Ivorybills,” Allen wrote in 1937, “and there is no complete description of an immature bird.” But that would soon change.

On his initial solo trip to the Singer Tract, Tanner became the first person to provide such a description, after watching two adults feed a nestling in a hole they’d carved high in a sweet gum tree. “It took me some time to realize that the bird in the hole was a young one; it seemed impossible,” he scribbled in his field notes. When he returned to those woods in early 1938, he discovered another nest hole, 55 feet off the ground in the trunk of a red maple. And in it he discovered another young ivory-bill.

Watching the nest for 16 days, Tanner noted that the bird’s parents usually foraged for about 20 minutes at midday. No ivory-bill had ever been fitted with an identifying band, so Tanner resolved to affix one to the nestling’s leg while its parents were away.

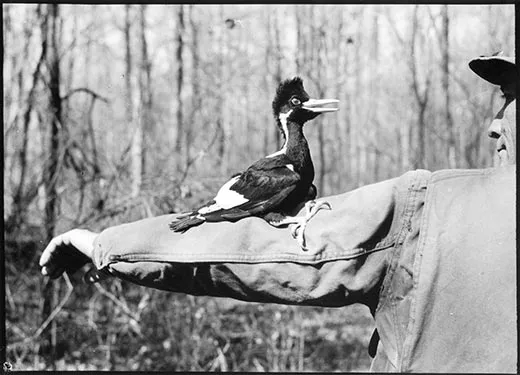

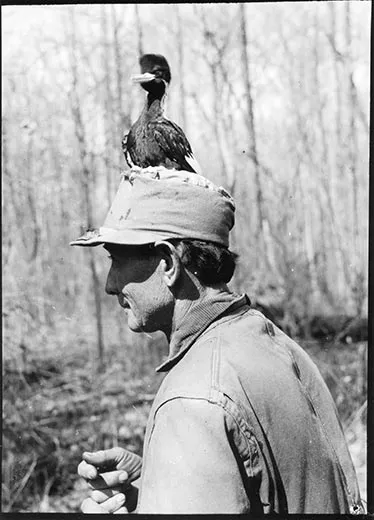

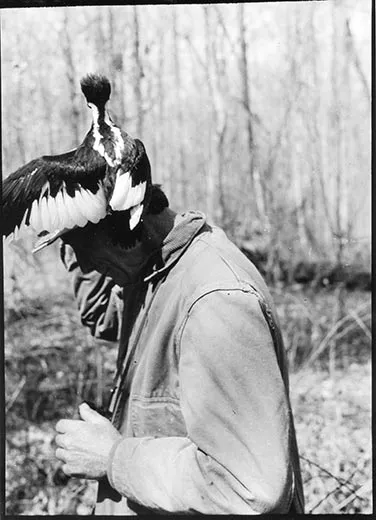

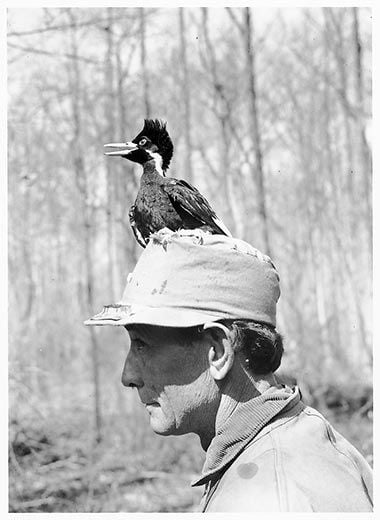

On his 24th birthday, March 6, 1938, Tanner decided to act. Up he went, on went the band—and out came the ivory-bill, bolting from the nest in a panic after Tanner trimmed a branch impeding his view of the nest hole. Too young to fly, the bird fluttered to a crash landing “in a tangle of vines,” Tanner wrote in his field notes, “where he clung, calling and squalling.” The ornithologist scrambled down the tree, retrieved the bird and handed it to his guide, J. J. Kuhn. “I surely thought that I had messed things up,” Tanner wrote. But as the minutes ticked away, he “unlimbered” his camera and began shooting, “jittery and nervous as all get-out,” unsure of whether he was getting any useful pictures. After exhausting his film, he returned the bird to its nest, “probably as glad as he that he was back there.”

When Tanner’s Cornell dissertation was published as The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker in 1942, the book included two pictures of the juvenile bird perched on Kuhn’s arm and head. Those frames, along with four others less widely printed—the only known photographs of a living nestling ivory-bill—have provided generations of birders with an image laden with fragile, possibly doomed, hope.

In a 1942 article for the ornithological journal The Wilson Bulletin, Tanner wrote “there is little doubt but that complete logging of the [Singer] tract will cause the end of the Ivorybills there.” The tract was indeed completely logged, and an ivory-bill sighting there in 1944 remains the last uncontested observation anywhere in the United States. Before he died at age 76 in 1991, Tanner, who taught for 32 years at the University of Tennessee, had sadly concluded that the species was extinct.

Three years ago, I began working with Nancy Tanner on a book about her husband’s fieldwork. In June 2009, she discovered a faded manila envelope in the back of a drawer at her home in Knoxville, Tennessee. In it were some ivory-bill images. At her invitation, I started going through them.

One of the first things I found was a glassine envelope containing a 2 1/4- by 3 1/4-inch negative. Holding it up to the light, I realized it was of the nestling ivory-bill from the Singer Tract—an image I had never seen. I quickly found another negative, then another and another. My hands began to shake. It turned out that Tanner had taken not 6 pictures on that long-ago March 6, but 14. As a group, they show the young bird not frozen in time, but rather clambering over Kuhn like a cat on a scratching post, frightened but vital.

Like almost any ornithologist, Jim Tanner would have liked to have been proved wrong about the ivory-bill’s fate. In 2005, the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology announced that searchers had seen an ivory-bill multiple times in ten months in the Big Woods in Arkansas. Other researchers, connected to Auburn University, reported 13 sightings in 2005 and 2006 along the Choctawhatchee River in Florida’s panhandle. In both cases, the sightings were made by experienced observers, including trained ornithologists. Yet neither group’s documentation—including a 4.5-second video of a bird in Arkansas—has been universally accepted. So the wait for incontrovertible evidence continues. Photographs like the ones Jim Tanner took in 1938 would do nicely.

Stephen Lyn Bales is a naturalist in Knoxville. His book about James Tanner, Ghost Birds, is due out this month.