A Level Playing Field for Science

I suppose, in a way, I should thank the woman who tried to compliment me when I was in high school by saying that I was too pretty for science

I suppose, in a way, I should thank the woman who tried to compliment me when I was in high school by saying that I was too pretty for science. What she was really saying was that girls don't belong in science, and that got me so riled up I'm still ticked off nearly two decades later. But at least she gave me something to write about—and I frequently do (just check out our Women's History Month coverage).

I've often used this example from my own life when arguing with people who don't believe that any gender bias exists in science. I'll admit that a single anecdote isn't evidence (simply a way of humanizing the situation), but I've got plenty of real evidence, including the new report, "Why So Few?," to back me up and explain how, even in the 21st century, women and girls are getting elbowed out from the fields of science and math.

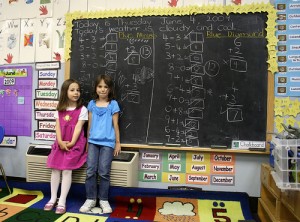

It starts when we're young. Some elementary school teachers pass on math fear to their female—and only their female—students and unknowingly promote the idea that boys are better than girls in math and science. Math performance suffers. As they grow up, girls are inundated with stereotypes (girls are princesses while boys build things) that tell them that girls have no place in science. It's easier to avoid taking calculus than buck a system that says you don't belong there, so it shouldn't be any surprise that some girls take the easier path. By high school, girls are taking fewer Advanced Placement exams in math, physics, chemistry and computer science, and in college, they're still vastly outnumbered in physics, engineering and computer science departments.

If a woman makes it through graduate school (which can be even more difficult if she decides to become a parent) and into the work world, there's a host of problems. She'll have to be better than her male counterparts: one study of postdoctoral applicants showed that women had to have published 3 more papers in a prestigious journal or 20 more in specialty journals to be judged as worthy as the men. Once hired, she may be the only woman on the faculty (Harvard, for example, just tenured its first female math professor). She's working in a setting designed around the lives of married men who had wives to take care of things, like raising children. When other researchers write letters of recommendation about her, those letters more likely refer to her compassion and teaching and avoid referring to her achievements and ability. And if she's successful, she'll be rated lower on the likability scale, which may sound minor but can have profound effects on evaluations, salary and bonuses.

But if women are getting edged out from math and science, is that bad for just women or is there a larger concern? I would argue for the latter, and I'm not alone. Meg Urry, a Yale University astronomer, wrote last year in Physics & Society (emphasis added):

Many scientists believe that increasing diversity is a matter of social engineering, done for the greater good of society, but requiring a lowering of standards and thus conflicting with excellence. Others understand that there are deep reasons for the dearth of women wholly unrelated to the intrinsic abilities of women scientists which lead to extra obstacles to their success. Once one understands the bias against women in male-dominated fields, one must conclude that diversity in fact enhances excellence. In other words, the playing field is not level, so we have been dipping more deeply into the pool of men than of women, and thus have been unknowingly lowering our standards. Returning to a level playing field (compensating for bias) will therefore raise standards and improve our field. Diversity and excellence are fully aligned.

I want a level playing field for science for many reasons (I don't want little girls to be taught to fear math; I'd like my female friends in science to be judged by the same standards my brother, a post-doc, is; I'm tired of hearing that someone was the "first woman" to do anything a guy has already done), but this is really a larger issue. We need to make sure that we aren't weeding out women from science so that we're not weeding out people who could be great scientists. How sad would it be to know that we don't have, say, a cure for cancer or a revolutionary fuel source because a girl or woman was dissuaded from the path that would have taken us there?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)