A New Species Bonanza in the Philippines

Sharks, starfish, ferns and sci-fi-worthy sea creatures have been discovered in a new massive survey

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Philippines-species-Jim-Shevoc-631.jpg)

After six weeks in the Philippines trawling the ocean floor, canvassing the jungly flanks of volcanoes and diving in coral reefs, scientists believe they have discovered more than 300 species that are new to science. Their research constituted the largest, most comprehensive scientific survey ever conducted in the Philippines, one of the most species-rich places on earth.

The survey, led by the California Academy of Sciences, brought scores of bizarre and unexpected creatures into the annals of life as we know it. It revealed more than 50 kinds of colorful new sea slugs, dozens of spiders and three new lobster relatives that squeeze into crevices rather than carry shells on their backs. The scientists found a shrimp-eating swell shark that lives 2,000 feet under the sea, a starfish that feeds exclusively on sunken driftwood and a cicada whose call sounds like laughter.

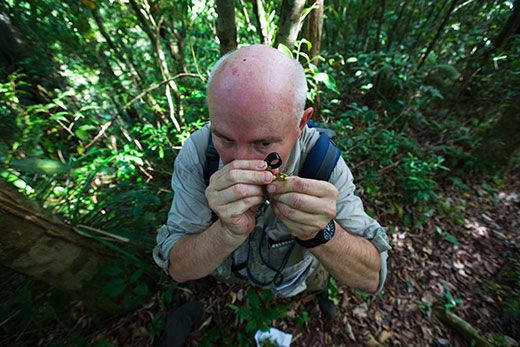

For two weeks I shadowed teams of scientists—from seahorse specialists to spider experts—as they surveyed reefs, rain forests and the South China Sea. On a deep-sea vessel, scientists dropped traps and nets to obtain a glimmer of the life that exists in the shadowy depths. They surrounded each haul excitedly as it was deposited on deck, picking through the curious sea life and discarding the garbage that inevitably accompanied it. “To see live stalk crinoids”—feather stars—“come up that I’ve only seen as preserved specimens is like a scientist’s dream world!” said invertebrate zoologist Terrence Gosliner, who led the expedition, one afternoon as he sorted spindly starfish and coral from candy wrappers.

Three new species of deep-sea “bubble snails” that possess fragile, translucent, internal shells arrived in one trawl, along with a snake eel and two new “armored corals” called primnoids, which protect themselves against predatory nibbles from fish by growing large, spiky plates around each soft polyp. Ten-inch-long giant isopods as imagined by science fiction turned up in a trap. “If you saw District 9 I’m sure they modeled the faces of the aliens off these,” said marine biologist Rich Mooi, who studies sea urchins and sand dollars. Later that evening, the catch yielded several two-foot-long, mottled swell sharks that inflate their stomach with water to bulk up and scare off other predators.

“When I watch the trawl come up it’s like a window onto the frontier,” said Mooi. “You start going through this material wondering, ‘What are they doing down there? Are they interacting with each other?’ We’ve seen a very tiny percentage of that sea bottom—three-quarters of the planet is obscured by this endlessly restless mass of water you can’t see through.”

Many of the new species found in the survey had evaded science because of their small size—the 30 new species of barnacles discovered measure just fractions of an inch in length—while others lived in areas rarely visited by humans. A primitive, fernlike plant called a spikemoss was found growing on the precipitous upper slopes of a 6,000-foot volcano. “Our scientific understanding of this part of the world is still in its infancy,” said Gosliner. “For people interested in biodiversity and the distribution of organisms and evolution, the Philippines is a treasure trove.”

Yet it is a gravely imperiled treasure trove. The rate of species extinction in the Philippines is “1,000 times the natural rate,” according to the country’s Department of Environment and Natural Resources, because of deforestation, coastal degradation, unsustainable use of resources, climate change, invasive species and pollution. A recent study by Conservation International found that just 4 percent of the Philippines' forests remained as natural habitat for endemic species, and according to the World Wildlife Fund, destructive commercial fishing has left only 5 percent of coral reefs in the Philippines in excellent condition.

Scientists described the expedition this spring as a kind of emergency response. “We’re living in a burning house,” said Mooi. “In order for firemen to come in and make an effective rescue they need to know who’s in those rooms and what rooms they’re in. When we do biodiversity surveys like this we’re doing nothing less than making a tally of who’s out there, who needs to be paid attention to, and how can we best employ the resources we have to conserve those organisms.”

For years scientists have recognized a 2.2-million-square-mile area around Malaysia, Papua New Guinea and the Philippines as being home to the world’s highest diversity of marine plants and animals. It’s known as the Coral Triangle and considered the Amazon basin for marine life. The waters harbor 75 percent of the planet's known coral species and 40 percent of its coral reef fish.

In 2005 Kent Carpenter, an ichthyologist at Old Dominion University, identified the core of that diversity. Overlaying global distribution maps for nearly 3,000 marine species, including fishes and corals, sea turtles and invertebrates, Carpenter found that the highest concentration of marine species on the planet existed in the central Philippines. “I fell off my chair—literally—when I saw that,” Carpenter recalled recently. He dubbed the region “the Center of the Center.”

The reasons for this are not entirely understood. The 7,107 islands that make up the Philippine Archipelago constitute the second-largest island chain in the world after Indonesia. The islands converged over millions of years from latitudes as disparate as those of present-day Hong Kong and Borneo, and they may have brought together temperate and tropical fauna that managed to get along in a crowded environment.

Another possible explanation is that the Philippines has a higher concentration of coastline than any country except Norway, providing a lot of habitat. It is also a place where species are evolving more rapidly than elsewhere. Populations become isolated from other populations due to oceanographic features such as swirling currents known as gyres. The populations then diverge genetically and become new species. “The only place on the planet where you have all of the above is in the Central Philippines,” said Carpenter.

A prime location for this diversity is the Verde Island Passage, a busy commercial sea route off Luzon Island, the largest island in the archipelago. During two decades of diving in the Verde Island Passage, Gosliner, the world’s foremost expert in nudibranchs, or sea slugs, has documented more than 800 species, half of them new to science. There are more species of soft corals at just one dive site than in all of the Caribbean. “Every time I go into the water here I see something I’ve never seen before,” he said.

One afternoon, Gosliner emerged from a dive into the shallow water reefs clutching a plastic collection bag that contained two nudibranchs, one colored a bright purple with orange tentacles. “Two new nudis!” he called out. “And the black and electric blue nudibranchs were mating like crazy down there. There were egg masses everywhere. They were having a good ole time.”

Unlike land slugs, nudibranchs have bright colors that advertise toxic chemicals in their skin. These chemicals may have pharmaceutical value, and several are in clinical trials for HIV and cancer drugs. Gosliner explained that the presence of nudibranchs, which feed on a wide variety of sponges and corals, “are a good indication of the health and diversity of the ecosystem.”

The Verde Island Passage ecosystem has faced immense pressures over the past few decades. In the 1970s, Carpenter worked as a Peace Corps volunteer with the Philippines Bureau of Fisheries. “Every 50 feet you’d see a grouper the size of a Volkswagen Bug, big enough to swallow a human being,” he recalls. Today, large predatory fish like sharks are virtually absent. Fishermen now harvest juveniles that haven’t had a chance to reproduce; “it’s at the very level where you can’t get any more fish out of oceans here,” says Carpenter. Destructive fishing methods have devastated the area’s coral. Illegal trade has exacted a further toll; this spring, Filipino officials intercepted a shipment of endangered sea turtles and more than 21,000 pieces of rare black corals bound for mainland Asia, for the jewelry trade.

“There’s a lot of good policies and regulations in place in the country, but the main weakness right now is enforcement,” says Romeo Trono, country director for Conservation International.

The Philippines has more than 1,000 marine protected areas, more than any country in the world, but only a few, Carpenter and other scientists say, are well managed. For 30 years, Apo Island, in the southern Philippines, has been held as a model for community-managed marine reserves. In 1982 a local university suggested the community declare 10 percent of the waters around the island a “no take” zone for fishermen. Initially resistant, the community eventually rallied behind the reserve after seeing how an increase in fish numbers and sizes inside the sanctuary spilled over into the surrounding waters. They established regulations against destructive fishing and a volunteer "marine guard" (called bantay dagat) to patrol the fishing grounds and prevent encroaching from outsiders. User fees from the marine sanctuary generate nearly $120,000 per year, and the tourist industry surged after the marine ecosystem recovered.

“Where marine protected areas have been established and populations of animals and fishes have been allowed to recover, they recover very well and very quickly,” says Gosliner. “The difference between diving in a marine protected area versus an area right next to it is like night and day.”

Over the next several months, California Academy scientists will use microscopes and DNA sequencing to confirm and describe these new species. The species lists and distribution maps created during the expedition, they hope, will help to identify the most important locations for establishing or expanding marine protected areas, as well as areas for reforestation that will reduce erosion and subsequent sedimentation damage to the reefs.

But for the scientists, the survey is just the beginning. “Being able to document the richest and most diverse marine environment on the planet” will help them “get an understanding of what the dimensions of diversity are,” said Gosliner. “We really don’t know the answer to that fundamental question.”

Andy Isaacson is a writer and photographer who lives in Berkeley, California. His reporting was made possible by a grant from Margaret and Will Hearst that funded the expedition.