A Puffin Comeback

Atlantic puffins had nearly vanished from the Maine coast until a young biologist defied conventional wisdom to lure them home

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Puffins-Project-Puffin-631.jpg)

Impossibly cute, with pear-shaped bodies, beak and eye markings as bright as clown makeup and a wobbly, slapstick walk, Atlantic puffins were once a common sight along the Maine coast. But in the 19th and early 20th centuries people collected eggs from puffins and other seabirds for food, a practice memorialized in the names of Eastern Egg Rock and other islands off the coast of New England. Hunters shot the plump birds for meat and for feathers to fill pillows and adorn women’s hats.

By 1901, only a single pair of Atlantic puffins was known to nest in the United States—on Matinicus Rock, a barren island 20 miles from the Maine coast. Wildlife enthusiasts paid the lighthouse keeper to protect the two birds from hunters.

Things began to change in 1918, when the Migratory Bird Treaty Act banned the killing of many wild birds in the United States. Slowly, puffins returned to Matinicus Rock.

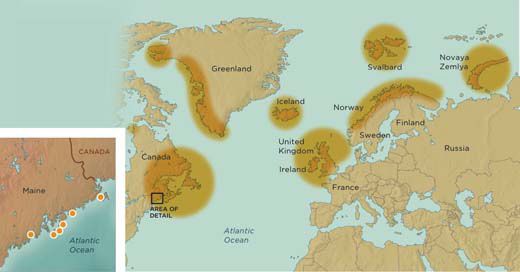

But not to the rest of Maine. Islands that puffins had once inhabited had become enemy territory, occupied by colonies of large, aggressive, predatory gulls that thrived on the debris generated by a growing human population. Though puffins endured elsewhere in their historic range—the North Atlantic coasts of Canada, Greenland, Iceland and Britain—by the 1960s the puffin was all but forgotten in Maine.

In 1964, then 18-year-old Stephen Kress was so smitten with nature that he signed up to spend the summer washing dishes at a National Audubon Society camp in Connecticut. There Carl Buchheister, president of the Audubon Society, entertained the kitchen crew with stories about his seabird research on the cliffs of Matinicus Rock. Kress, who had grown up in Columbus, Ohio, went on to attend Ohio State, where he earned a degree in zoology; he then worked as a birding instructor in New Brunswick, Canada, where he visited islands overflowing with terns, gulls—and puffins.

When, in 1969, Kress landed his dream job, as an instructor at the Hog Island Audubon Camp on the Maine coast, the islands he visited seemed desolate, with few species other than large gulls. He wondered if puffins could be transplanted so the birds might once again accept these islands as home. No one had ever tried to transplant a bird species before.

“I just wanted to believe it was possible,” Kress says.

Though a handful of wildlife biologists supported him, others dismissed the idea. There were still plenty of puffins in Iceland, some pointed out; why bother? Others insisted the birds were hard-wired to return only to the place where they had hatched and would never adopt another home. Still others accused Kress of trying to play God.

Kress argued that bringing puffins back to Maine could help the entire species. As for playing God, Kress didn’t see a problem. “We’d been playing the Devil for about 500 years,” says Tony Diamond, a Canadian seabird researcher who has collaborated with Kress for decades. “It was time to join the other side.”

Kress went to work preparing a place for puffin chicks on Eastern Egg Rock, a seven-acre granite island about eight miles off the coast of Bremen, Maine. Officials with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service shot dozens of gulls and drove off many more to make the island safer for young puffins.

In the summer of 1973, Kress, a research assistant named Kathleen Blanchard and Robert Noyce, a sympathetic summer neighbor (and the founder of Intel), went to Newfoundland’s Great Island, one of the largest puffin colonies in North America. It was the first of more than a dozen trips that the Audubon-sponsored “Project Puffin” would make to Great Island.

During each trip, Kress and his team, accompanied by Canadian Wildlife Service staffers, clambered up the island’s steep banks and plunged their arms into the long, narrow burrows that puffins dig in soil. Sometimes they extracted a chick, but often they got only a nasty nip from an adult puffin. In total, they collected hundreds of chicks, nestling each in a soup can and storing the cans in carrying cases made for the journey. Making their way past amused customs officials, they flew home to Maine, and, in the wee hours, headed out to Eastern Egg Rock or to nearby Hog Island, where they deposited the chicks in hand-dug burrows.

Kress and his assistants became dutiful puffin parents, camping on the islands and leaving fish inside the burrows twice each day. Nearly all the chicks survived their international adventure, and by late summer were big enough to fledge. At night, Kress hid behind boulders observing the burrows, sometimes glimpsing a young puffin as it hopped into the water and paddled out to sea.

Because young puffins spend a few years at sea before returning home to nest, Kress knew he was in for a long wait. Two years passed, three, then four. There was no sign of homecoming puffins.

Kress also knew that the birds were extremely social, so he decided to make Eastern Egg Rock appear more welcoming. He got a woodcarver named Donald O’Brien to create some puffin decoys, and Kress set them out on the boulders, hoping to fool a live puffin into joining the crowd.

Finally, in June 1977, Kress was steering his powerboat toward the island when a puffin landed in the water nearby—a bird wearing leg bands indicating it had been transplanted from Newfoundland to Eastern Egg Rock two years earlier.

But no puffins nested on Eastern Egg Rock that year, or the next. Or the next. A few of the transplanted birds nested with the existing puffin colony on Matinicus Rock, but not one had accepted Eastern Egg Rock as its home.

Shortly before sunset on July 4, 1981, Kress was scanning Eastern Egg Rock with his telescope when he spotted a puffin, beak full of fish, scrambling into a rocky crevice. The bird hopped out, empty-beaked, and flew away, while another adult puffin stood by watching. It was the long-hoped-for evidence of a new chick on the island.

“After 100 years of absence and nine years of working toward this goal,” Kress wrote in the island logbook that evening, “puffins are again nesting at Eastern Egg Rock—a Fourth of July celebration I’ll never forget.”

Today, Eastern Egg Rock hosts more than 100 pairs of nesting puffins. Boatloads of tourists chug out to peer at them through binoculars. Kress and his “puffineers”—biologists and volunteers—have also reintroduced puffins to Seal Island, a former Navy bombing range that now serves as a national wildlife refuge. On Matinicus Rock, also a national wildlife refuge, the puffin population has grown to an estimated 350 pairs. Razorbills, a larger, heavier cousin to the puffin, also nest among the boulders; common and Arctic terns nest nearby. In all, a century after Atlantic puffins almost disappeared from the United States, at least 600 pairs now nest along the Maine coast.

Today seabirds around the world benefit from techniques pioneered by Kress and his puffineers. Bird decoys, recorded calls and in some cases, mirrors—so seabirds will see the movements of their own reflections and find the faux colonies more realistic—have been used to restore 49 seabird species in 14 countries, including extremely rare birds such as the tiny Chatham petrel in New Zealand and the Galápagos petrel on the Galápagos Islands.

“A lot of seabird species aren’t willing to come back to islands on their own—they’re not adventurous enough,” says Bernie Tershy, a seabird researcher at the University of California at Santa Cruz. “So in the big picture, Steve’s work is a critical component of protecting seabirds.” With more and larger breeding colonies, seabirds are more likely to survive disease outbreaks, oil spills and other disasters.

Despite these successes, seabirds are still declining more quickly than any other group of birds, largely because of invasive predators, habitat loss, pollution and baited hooks set out by longline fishing fleets; many species will also likely suffer as climate change leads to rising sea levels and skimpier food supplies, says Tershy.

Project Puffin tactics are already deployed against these new threats. For example, the Bermuda petrel lives on a group of tiny, low-lying atolls off the Bermuda coast, where it is vulnerable to mere inches of sea-level rise or a single powerful storm. Scientists recently employed Kress’ techniques to relocate petrel chicks to higher ground, a nearby island called Nonsuch where the birds had been driven off by hunters and invasive species. Last summer, a petrel chick hatched and fledged on Nonsuch Island—the first to do so in almost 400 years.

Eastern Egg Rock has a human population of three, minimal electricity and no plumbing. Thousands of gulls swoop over the island, their cries combining into a near-deafening cackle. Terns, their narrow white wings angled like airborne origami sculptures, dive for human heads, the birds’ shrill scolds adding to the cacophony. Underfoot, gangs of chubby tern chicks scuttle in and out of the grass, testing their wings with tentative flaps.

On the boulders that rim the island, more seabirds loaf in the midsummer sun, gathering in cliques to gossip and preen—looking for all the world like an avian cocktail party.

A puffin in flight, stumpy wings whirring, careers in for a landing. Orange feet spread wide, it approaches a boulder, wobbles in the air for an instant, and—pop!—hits the rock, a fish shining in its striped, oversized beak. The puffin hops into a crevice between two rocks, presumably to deliver the fish to a hungry chick, and bounds back up to mingle with other puffins before its next expedition.

Each puffin pair raises a single chick. Once the young bird fledges, it heads south, but no one knows exactly where the juveniles spend their first two to three years. Though puffins are speedsters—they can reach 55 miles an hour in flight—their greatest talents are displayed at sea, where they use their feet and wings to maneuver expertly underwater.

“Never let it be said that puffins are awkward,” says Kress, who is director of Project Puffin and affiliated with Cornell University. “They can dive more than 200 feet in water, they can burrow like groundhogs and they can scamper over rocks. They’re all-purpose birds.”

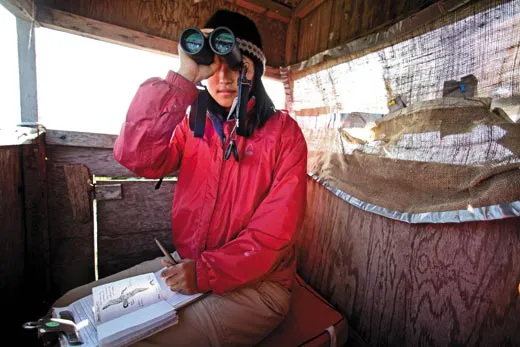

On Eastern Egg Rock, Kress sits in a cramped plywood bird blind on the edge of the island, watching the seabirds toil for their chicks. Even after countless hours hunched behind binoculars, he’s still charmed by his charges.

Kress once imagined that he could one day leave the islands for good, the puffin colonies restored and the project’s work complete. He was wrong.

It became clear that two large gull species—the herring and black-backed gulls that prey on puffin chicks—weren’t going away. Kress had to play God again, this time to give puffins another ally in their battle against gulls: terns.

Terns look delicate and graceful aloft, but they are fighters, known for pugnacious defense of their nests. Working on the island, Kress wears a tam-o’-shanter so that angry terns will swipe at its pompom and not his head. Scott Hall, research coordinator for Project Puffin, wears a baseball cap fitted with bobbing, colorful antennae. Kress believed that the terns, once established, would drive off predatory gulls and act as a “protective umbrella” for the milder-mannered puffins. Unlike gulls, terns don’t prey on puffin eggs and chicks.

He and his colleagues used tern decoys, as they had with puffins, and played recorded tern calls through speakers to attract the birds. Again, their tricks worked: well over 8,400 pairs of terns, including 180 pairs of endangered roseate terns, now nest on the Maine islands where Kress and his team work, up from 1,100 pairs in 1984. But gulls continue to hover on the edges of the islands, waiting for an opportunity to feast on puffin and tern chicks.

Only one species, it seemed, could protect the puffins, the terns and the decades of hard work that Kress and his colleagues had invested: human beings. “People are affecting the ecosystem in all kinds of profound ways, underwater and above water,” Kress says. “Just because we bring something back doesn’t mean it’s going to stay that way.”

So each summer, small groups of puffineers live as they have for almost 40 years, in the midst of the seabird colonies on seven islands, where they study the birds and their chicks and defend them against gulls.

On Eastern Egg Rock, Juliet Lamb, a wildlife conservation graduate student at the University of Massachusetts, is back for her fourth summer of living in a tent. She says she thrives on the isolation and even turns down occasional opportunities to visit the mainland for a hot shower. “I’d probably live out here all year if I could,” she adds with a laugh. She and two other researchers spend hours each day in bird blinds arrayed on the perimeter of the island watching puffins and terns feed their chicks. As the supervisor of island operations, Lamb also divvies up cooking and outhouse-cleaning duties, maintains the propane refrigerator and makes sure the island’s single cabin—which serves as kitchen, pantry, lounge and office—stays reasonably uncluttered. When her chores are finally done, she might climb the ladder to the cabin roof, French horn in hand, and practice until sunset.

Some days are decidedly less peaceful. When the biologists arrive in Maine each spring, they go through firearms training at a local firing range, learning to shoot .22-caliber rifles. In 2009, with permission from state and federal wildlife officials, Lamb and her assistants shot six herring and black-backed gulls, hoping to kill a few especially persistent ones and scare off the rest. Because of a worrying decline in roseate terns, they also destroyed the nests of laughing gulls, a smaller, less threatening species that occasionally eats tern eggs and chicks.

Kress and his colleagues are still dreaming up ways to replace themselves as island guardians.They’ve experimented with a “Robo Ranger,” a mechanized mannequin designed to pop up at random intervals and scare gulls off. The souped-up scarecrow wears a yellow slicker and a rubber Arnold Schwarzenegger mask. To teach the gulls that the mannequin is a serious threat, the biologists sometimes dress up in its costume and shoot a few. But mechanical problems have felled the Robo Ranger for now, leaving people as the puffins’ and terns’ only line of defense. The puffineers’ work is never done.

Michelle Nijhuis has written for Smithsonian about aspen trees, the Cahaba River and Henry David Thoreau. José Azel is a photographer based in rural western Maine.