A Quest to Save the Orangutan

Birute Mary Galdikas has devoted her life to saving the great ape. But the orangutan faces its greatest threat yet

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Orangutan-Doyok-reserve-631.jpg)

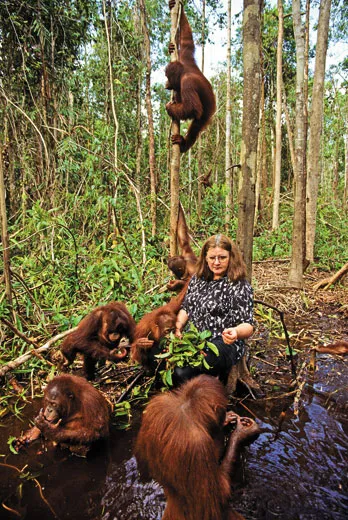

Darkness is fast approaching at Camp Leakey, the outpost in a Borneo forest that Biruté Mary Galdikas created almost 40 years ago to study orangutans. The scientist stands on the porch of her weathered bungalow and announces, "It's party time!"

There will be no gin and tonics at this happy hour in the wilds of Indonesia's Central Kalimantan province. Mugs of lukewarm coffee will have to do. Yes, there's food. But the cardboard boxes of mangoes, guavas and durians—a fleshy tropical fruit with a famously foul smell—are not for us humans.

"Oh, there's Kusasi!" Galdikas says, greeting a large orangutan with soulful brown eyes as he emerges from the luxuriant rain forest surrounding the camp. Kusasi stomps onto the porch, reaches into a box of mangoes and carries away three in each powerful hand. Kusasi was Camp Leakey's dominant male until a rival named Tom took charge several years ago. But Kusasi, who weighs in at 300 pounds, can still turn aggressive when he needs to.

"And Princess!" Galdikas says, as another "orang"—noticeably smaller than Kusasi but every bit as imposing, especially to a newcomer like me—steps out of the bush. "Now Princess is really smart," she says. "It takes Princess a while, but if you give her the key she can actually unlock the door to my house."

"And Sampson! And Thomas!" Galdikas smiles as these juvenile males bare their teeth and roll around in the dirt, fighting. They are fighting, right? "Noooo, they're just playing," Galdikas tells me. "They are just duplicating how adult males fight. Sampson makes wonderful play faces, doesn't he?"

No Camp Leakey party would be complete without Tom, the reigning alpha male and Thomas' older brother. Tom helps himself to an entire box of mangoes, reminding Kusasi who's boss. Tom bit Kusasi severely and took control, Galdikas tells me, nodding toward Tom and whispering as if Kusasi might be listening. "Be careful," she says as the new monarch brushes past me on the porch. "He's in a bad mood!"

And then, just as suddenly as they appeared, Tom, Kusasi and the gang leave this riverside camp to resume their mostly solitary lives. Galdikas' mood darkens with the sky. "They don't say goodbye. They just melt away," she says, her eyes a bit moist. "They just fade away like old soldiers."

Galdikas, 64, has been living among orangutans since 1971, conducting what has become the world's longest continuous study by one person of a wild mammal. She has done more than anyone to protect orangutans and to help the outside world understand them.

Her most chilling fear is that these exotic creatures with long arms, reddish brown hair and DNA that is 97 percent the same as ours will fade into oblivion. "Sometimes I wake up in the middle of the night and I just clutch my head because the situation is so catastrophic," Galdikas says in a quiet, urgent voice. "I mean, we're right at the edge of extinction."

Galdikas has been sounding the "e" word for decades while battling loggers, poachers, gold miners and other intruders into the orangutans' habitat. And now a new foe is posing the most serious threat yet to Asia's great orange apes. Corporations and plantations are rapidly destroying rain forests to plant oil palms, which produce a highly lucrative crop. "Words cannot describe what palm oil companies have done to drive orangutans and other wildlife to near-extinction," Galdikas says. "It's simply horrific."

According to the Nature Conservancy, forest loss in Indonesia has contributed to the death of some 3,000 orangutans a year over the past three decades. All told, the world's fourth most populous nation is losing about 4.6 million acres of forest every year, an area almost as large as New Jersey. A 2007 United Nations Environment Programme report, "The Last Stand of the Orangutan: State of Emergency," concluded that palm oil plantations are the primary cause of rain forest loss in Indonesia and Malaysia—the largest producers of palm oil and the only countries in the world where wild orangutans can still be found. Between 1967 and 2000, Indonesia's palm oil plantation acreage increased tenfold as world demand for this commodity soared; it has almost doubled in this decade.

With 18 million acres under cultivation in Indonesia and about as much in Malaysia, palm oil has become the world's number one vegetable oil. The easy-to-grow ingredient is found in shampoos, toothpaste, cosmetics, margarine, chocolate bars and all manner of snacks and processed foods. Global sales are expected only to increase as demand for biofuels, which can be manufactured with palm oil, soars in the coming years.

Palm oil companies don't see themselves as the bad guys, of course. Singapore-based Wilmar International Ltd., one of the world's largest producers, says it is "committed to ensuring the conservation of rare, threatened and endangered species." The companies point out that they provide employment for millions of people in the developing world (the oil palm tree is also grown in Africa and South America), while producing a shelf-stable cooking oil free of trans fats. As fuel, palm oil does not contribute as much greenhouse gas to the atmosphere as fossil fuels, although there is a furious debate over whether the carbon dioxide absorbed by the palm trees makes up for the greenhouse gases dispersed into the atmosphere when rain forests are burned and plowed to create plantations.

Nowhere is the clash between planters and conservationists more important than in Borneo, an island divided into Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei. Its rain forests are among the most ecologically diverse in the world, with about 15,000 types of plants, more than 600 species of birds and an animal population that also includes the clouded leopard and pygmy elephant. "Camp Leakey still looks like a primeval Eden," Galdikas says. "It's magical." Her camp is in Tanjung Puting National Park, a one-million-acre reserve managed by the Indonesian government with help from her Orangutan Foundation International (OFI). But the habitat is not fully protected. "If you go eight kilometers north [of the camp], you come into massive palm oil plantations," she says. "They go on forever, hundreds of kilometers."

So far, in a bid to outmaneuver oil palm growers, Galdikas' OFI has purchased several hundred acres of peat swamp forest and partnered with a Dayak village to manage 1,000 more. And during my five days in Kalimantan, she promises to show me the fruits of her work not only as a scientist and conservationist but as a swampland investor as well. Having grown up in Miami, I can't help but think of the old line, "If you believe that, I've got some swampland in Florida to sell you," implying the stuff is utterly worthless. In Borneo, I learn, swampland is coveted.

Biruté Mary Galdikas wasn't looking to become a real estate magnate when she arrived on the island four decades ago to study orangutans. She had earned a master's degree in anthropology at UCLA (a PhD would follow). Her research in Borneo was encouraged by legendary paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey, whose excavations with his wife, Mary, in East Africa unearthed some of the most important fossils and stone tools of our hominid ancestors. (Leakey also mentored chimp researcher Jane Goodall and gorilla researcher Dian Fossey; he called them the "trimates.")

The Borneo that greeted Galdikas and her then-husband, photographer Rod Brindamour, was one of the most isolated and mysterious places on earth, an island where headhunting was part of the collective memory of local tribes.

To locals, Galdikas was very much an oddity herself. "I started crying the first time I saw Biruté because she looked so strange. She was the first Westerner I'd ever seen!" says Cecep, Camp Leakey's information officer, who was a boy of 3 when he first glimpsed Galdikas 32 years ago. Cecep, who, like many Indonesians, goes by a single name, says he stopped crying only after his mother assured him she was not a hunter: "She's come here to help us."

The daughter of Lithuanians who met as refugees in Germany and immigrated first to Canada, then the United States, Galdikas has paid dearly for the life she has chosen. She has endured death threats, near-fatal illnesses and bone-chilling encounters with wild animals. She and Brindamour separated in 1979, and their son, Binti, joined his father in Canada when he was 3 years old. Both parents had worried that Binti was not being properly socialized in Borneo because his best friends were, well, orangutans. Galdikas married a Dayak chief named Pak Bohap and they had two children, Jane and Fred, who spent little time in Indonesia once they were teenagers. "So this hasn't been easy," she says.

Still, she doesn't seem to have many regrets. "To me, a lot of my experiences with orangutans have the overtones of epiphanies, almost religious experiences," she says with a far-off gaze. "Certainly when you are in the forest by yourself it's like being in a parallel universe that most people don't experience."

Orangutans live wild only on the islands of Borneo and Sumatra. The two populations have been isolated for more than a million years and are considered separate species; the Bornean orangutans are slightly larger than the Sumatran variety. Precious little was known about orangutan biology before Galdikas started studying it. She has discovered that the tree-dwelling animals spend as much as half the day on the ground. Adult males can reach five feet tall (though they rarely stand erect) and weigh up to 300 pounds. "They're massive," says Galdikas. "That's what you notice more than height." Females weigh about half as much and are four feet tall. Both sexes can live 30 to 50 years. At night they sleep in nests of sticks they build high in the treetops.

Galdikas also has documented that the orangs of Tanjung Puting National Park procreate about once every eight years, the longest birth interval of any wild mammal. "One of the reasons orangutans are so vulnerable is because they are not rabbits that can have a few litters every year," she says. After an eight-month pregnancy, females bear a single infant, which will remain with its mother for eight or nine years.

Galdikas has cataloged about 400 types of fruit, flowers, bark, leaves and insects that wild orangutans eat. They even like termites. Males usually search for food alone, while females bring along one or two of their offspring. Orangs have a keen sense of where the good stuff can be found. "I was in the forest once, following a wild orangutan female, and I knew we were about two kilometers from a durian tree that was fruiting," Galdikas says on the front porch of her bungalow at Camp Leakey. "Right there, I was able to predict that she was heading for that tree. And she traveled in a straight line, not meandering at all until she reached the tree."

Males are frighteningly unpredictable. Galdikas recalls one who picked up her front porch bench and hurled it like a missile. "It's not that they're malicious," Galdikas assures me, gesturing toward the old bench. "It's just that their testosterone surge will explode and they can be very dangerous, inadvertently." She adds, perhaps as a warning that I shouldn't get too chummy with Tom and Kusasi, "if that bench had hit somebody on the head, that person would have been maimed for life."

She also has made discoveries about how males communicate with one another. While it was known that they use their throat pouches to make bellowing "long calls," signaling their presence to females and asserting their dominance (real or imagined) to other males, she discerned a call reserved especially for fellow males; roughly translated, this "fast call" says: I know you're out there and I'm ready to fight you.

Along the way, Galdikas has published her findings in four books and dozens of other publications, both scientific and general interest; signed on as a professor at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia (she spends about half the year in Canada and the United States); and mentored hundreds of aspiring scientists, such as the four students from Scotland's University of Aberdeen who are at Camp Leakey during my visit. Their mission? To collect orangutan feces samples to trace paternity and measure the reproductive success of various males.

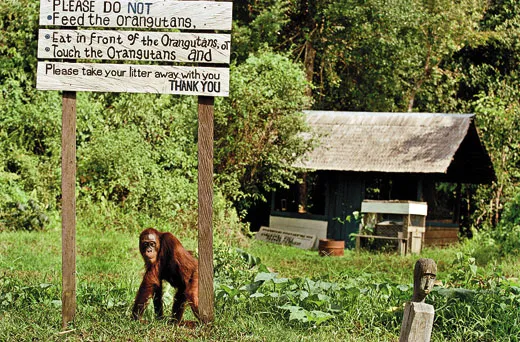

I ask Galdikas which orangutan riddles she has yet to solve. "For me," she says, "the big, abiding mystery is: How far did the original males travel here in Tanjung Puting, and where did they come from?" She may never know. The 6,000 remaining orangutans can no longer travel at will because of palm oil plantations surrounding the park, all created since 1971. When she began the study, she says, "orangutans could wander to the other side of Borneo if they felt like it. Now they're trapped. They get lost in these palm oil plantations and they get killed."

Galdikas says the killings are usually carried out by plantation workers who consider the animals pests, by local people who eat their meat and by poachers who slaughter females to capture their babies, which are then sold illegally as pets.

As recently as 1900, more than 300,000 orangutans roamed freely across the jungles of Southeast Asia and southern China. Today an estimated 48,000 orangutans live in Borneo and another 6,500 in Sumatra. Galdikas blames people for their decline: "I mean, orangutans are tough," she says. "They're flexible. They're intelligent. They're adaptable. They can be on the ground. They can be in the canopy. I mean, they are basically big enough to not really have to worry about predators with the possible exception of tigers, maybe snow leopards. So if there were no people around, orangutans would be doing extremely well."

To grow oil palm (Elaesis guineensis) in a peat swamp forest, workers typically drain the land, chop down the trees (which are sold for timber) and burn what's left. It's a procedure, Galdikas says, that not only has killed or displaced thousands of orangutans but also has triggered massive fires and sent huge amounts of carbon dioxide into the air, furthering climate change.

A hopeful sign came in 2007 when Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono partnered with nongovernmental organizations to launch a ten-year plan to protect the remaining orangutans. Without such protections against deforestation and illegal mining and logging, he predicted, "these majestic creatures will likely face extinction by 2050."

"Some of the palm oil plantations seem to be realizing that there is concern in the world about what they are doing," Galdikas says. "This to me is the best development."

But, Galdikas says, provincial officials in Central Kalimantan have done little to stop palm oil plantations from encroaching on Tanjung Puting. "That's why we're trying to buy as much forest land as we can, so we can actually make sure the palm oil companies can't buy it," she says. "It's absolutely a race against time."

Rain forest is cheap—as little as $200 an acre in recent years if it's far from a town. And Galdikas has a key advantage over the palm oil companies: she is trusted by the Dayak community. "People here respect Dr. Biruté as the scientist who devoted her life to fighting to save the orangutans," says Herry Roustaman, a tour guide who heads the local boatmen's association.

Galdikas takes me to see another prized piece of her real estate portfolio, a private zoo just outside Pangkalan Bun that her foundation bought for $30,000. The purchase was a "two-fer," she says, because it enabled her to preserve ten acres of rain forest and shut down a mismanaged zoo that appalled her. "I bought the zoo so I could release all the animals," she says. "There were no orangutans in this zoo. But there were bearcats, gibbons, a proboscis monkey, even six crocodiles."

A look of disgust creases her face as we inspect a concrete enclosure where a female Malay honey bear named Desi once lived. "Desi was just covered in mange when I first saw her," Galdikas says. "Her paws were all twisted because she tried to escape once and ten men pounced on her and they never treated the paw. They threw food at her and never went in to clean the cage because they were afraid of her. All she had for water was a small cistern with rain water in it, covered with algae. So I said to myself, 'I have to save this bear. This is just inhuman.'"

Galdikas' Borneo operation employs about 200 men and women, including veterinarians, caregivers, security guards, forest rangers, behavioral enrichment specialists (who seek to improve the physical and mental well-being of the captive orangutans), a feeding staff and eight local blind women who take turns holding the orphaned babies 24 hours a day.

"Orangutans like to eat," Galdikas says one morning as she leads two dozen orphaned baby orangutans on a daily romp though the 200-acre care center a few miles outside Pangkalan Bun. "We feed them five times a day at the care center and spend thousands of dollars on mangoes, jackfruits and bananas every month."

About 330 orphaned orangs live at the 13-year-old center, which has its own animal hospital with laboratory, operating room and medical records office. Most are victims of a double whammy; they lost their forest habitat when gold miners, illegal loggers or palm oil companies cleared it. Then their mothers were killed so the babies could be captured and sold as pets. Most came to Galdikas from local authorities. Kiki, a teenager who was paralyzed from the neck down by a disease in 2004, slept on a four-poster bed in an air-conditioned room and was pushed in a pink, blue and orange wheelchair before she died this year.

The juveniles will be released when they are between 8 and 10 years of age, or old enough to avoid being prey for clouded leopards. In addition to the fruits, the youngsters are occasionally given packages of store-bought ramen noodles, which they open with gusto. "If you look closely, you'll see each package has a tiny salt packet attached," says Galdikas. The orangutans carefully open the packets and sprinkle salt on their noodles.

Galdikas and I roar down the inky Lamandau River in a rented speedboat, bound for a release camp where she hopes to check up on some of the more than 400 orangutans she has rescued and set free over the years. "The orangutans at the release site we'll be visiting do attack humans," she warns. "In fact, we had an attack against one of our assistants a few days ago. These orangutans are no longer used to human beings."

But when we arrive at the camp, about an hour from Pangkalan Bun, we encounter only a feverish, emaciated male sitting listlessly beside a tree. "That's Jidan," Galdikas says. "We released him here a year and a half ago, and he looks terrible."

Galdikas instructs some assistants to take Jidan immediately back to the care center. She sighs. "There's never a dull moment here in Borneo," she says. (Veterinarians later found 16 air rifle pellets under Jidan's skin. The circumstances of the attack have not been determined. After a blood transfusion and rest, Jidan recuperated and was returned to the wild.)

On the dock of the release camp, I ask Galdikas if anyone can save the wild orangutan from extinction.

"Well, I've been here almost 40 years, and the situation is: You keep winning battles, but you keep losing the war," she says. "Will we win? Will we succeed?"

Her questions hang in the vaporous jungle air before she breaks her silence. She suggests that while the orangutans' habitat inside Tanjung Puting will likely survive the next 40 years, the forests outside the park will probably be glutted with oil palm plantations and inhospitable to orangs.

Stepping into the speedboat, Biruté Mary Galdikas says she's determined to protect Tom, Kusasi and future generations of her old soldiers. "Here in Borneo," she says softly, "I take things one day at a time."

Bill Brubaker wrote about Haitian art after the earthquake for the September issue of Smithsonian. Anup Shah and Fiona Rogers' photographs of gelada primates ran last year.