A Return to the Reefs

With the world’s coral reefs in crisis, the author’s childhood memories guide a far-reaching study of the problem in the Bahamas

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1a/57/1a57749a-c267-4a64-9c5d-c8d0739020d6/1200px-coral_outcrop_flynn_reef.jpg)

I couldn’t have been more than 5 years old when my father fitted me with my first pair of swim goggles. I waded out from the beach until the silky cool water reached my chest, and then I bent my knees until my head was below the surface. As if I’d passed through the looking glass like Alice, I was suddenly inside our living room aquarium with its colony of bright, tiny sea creatures.

My smiling, similarly begoggled father was beckoning in dreamlike slow motion. Easing through the silvery ceiling of the sea, through clouds of minnows, over the dancing white sand bottom, I swam out with him until the world changed from bright sand to beige-colored rocks fringed with plants and set with purple and yellow sea fans.

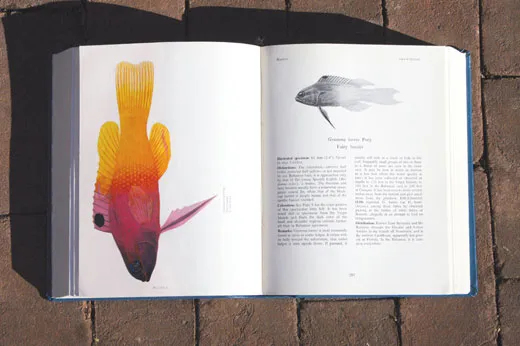

My father dove eight feet to the bottom, where I could see a little cave underneath a ledge, and beckoned again. Diving down to him was as easy as flying. Under the roof of the cave a living jewel was hanging upside down, shading from deep purple at its head to brilliant yellow at its tail. It turned sideways with a wave of a magenta fin and cocked a midnight blue eye. There was a click inside my head. It was one of those moments when the world arranges itself: from now on the sea would be a top priority for me.

The fish was called a fairy basslet, my father told me when we came up for air. He would know. At the time, he was engaged in the most comprehensive study ever done of fishes of the Bahama Islands. Although he’d never been to college and had no formal scientific training, he co-authored the 771-page Fishes of the Bahamas and Adjacent Tropical Waters, first published in 1968, that documents 507 species and is still considered the classic reference.

In many ways, this book is my sibling. I spent my childhood with it in the Bahamas, watching it grow and take shape and sometimes helping it along. As a boy, I participated in many of the collecting expeditions (at least 1 or 2 of the 65 new species introduced in the book were netted by me). I know the spots where my father collected specimens as well as I know the rooms in the house where I grew up.

Both my father, Charles C.G. Chaplin, and his co-author, James Böhlke, are gone now. But a scientist at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, which supported their research, decided that the specimens, notes, photographs and films they accumulated over 15 years provide a unique opportunity to compare the marine environment in the Bahamas then and now. In 2004, Dominique Dagit (who has since moved from the Academy to Millersville University in Pennsylvania) began one of the first 50-year retrospective studies of coral reef life.

As the only surviving member of the original research team, I returned to the Bahamas to show Dagit and her colleagues the sites where my father had collected specimens and made observations. It was the first time I’d been back since our house was sold in the 1970s, and what I found was shocking.

The world’s coral reefs are in trouble. According to the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network (GCRMN), an international consortium of scientists and volunteers, only 30 percent of reefs are healthy now, down from 41 percent in 2000. United States government agencies, conservation organizations and other scientists echo the point. A few go so far as to say that coral reefs in some areas may be doomed. In the Caribbean, the area of seafloor covered by live hard coral has decreased by 80 percent in the past 30 years.

A coral reef is actually a colony of small polyps, related to jellyfish, that secrete a limestone exoskeleton and nourish themselves mainly through a symbiotic relationship with photosynthesizing algae. Modern coral reefs as we know them have been accumulating since the Holocene Epoch 10,000 years ago. They are the largest durable biological constructions on earth, and support more kinds of species than any other marine environment. They sustain many fishes that people rely on for food, and they protect coastlines and attract tourists. A 1997 study estimated that reefs contribute $375 billion a year to the world’s economy.

The most serious threat to coral reefs—overshadowing natural cataclysms such as hurricanes, floods and tsunamis—is human activity. Overfishing, begun hundreds of years ago, has depleted the populations of many of the fishes that graze on algae and keep it from smothering the reefs. Runoff laden with sediment and pollutants further fuels the growth of algae and spreads harmful bacteria.

Even more threatening to coral reefs are greenhouse gases, notably carbon dioxide. Emitted into the atmosphere when fossil fuels are burned, carbon dioxide has become much more concentrated in seawater in the past 60 years, making the ocean more acidic and interfering with coral polyps’ ability to generate their limestone skeleton. More significantly, ocean temperatures have risen in recent years, and coral is so sensitive to change that a prolonged warming of less than 2 degrees Fahrenheit above normal can cause bleaching. In this frequently fatal condition, coral polyps expel their symbiotic algae and turn snowy white. During the 1998 El Niño-induced warming, 16 percent of the world’s reefs suffered bleaching, according to GCRMN; two-fifths of the damaged reefs have since recovered. Officials from the World Conservation Union warn that if global warming continues at the predicted rate, up to half of the world’s coral reefs may die within the next 40 years.

Evaluating threats to the world’s reefs is a matter of real urgency, yet it is no easy task. “Conventional ecological data are clearly inadequate,” writes reef ecologist Jeremy Jackson of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California, and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama. “Most observational records are much too short, too poorly replicated, and too uncontrolled to encompass even a single cycle of natural environmental variation.”

This is what makes my father’s legacy important.

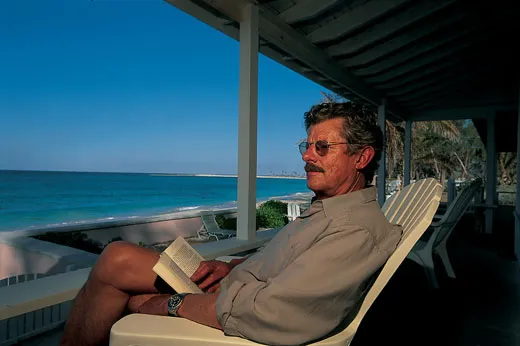

The house in which i grew up is across the harbor from Nassau and reachable only by boat. Ronnie and Joan Carroll run it as a bed-and-breakfast, and the place is still called the Chaplin House. Ronnie, a former commercial diver whose family has been in the Bahamas since the 1600s, ferried me over one May morning. “Nassau’s all shot to hell,” he said cheerfully, “but we’ve done our best to keep the old place the way your father left it.”

The house is on what used to be called Hog Island, where livestock was kept in the 18th century when Nassau was a pirate port. Now it’s called Paradise Island, site of a huge casino and resort complex, Atlantis, which looms pinkly over the harbor.

The harbor looked both more dilapidated and more glittery than I remembered. The wharves and sheds on the Nassau side were sagging and rusty, docked with tramp freighters from the Caribbean’s more notorious fever ports. Trading sloops from Haiti, with sails of rags, drifted in on the east wind with, Ronnie speculates, cargoes of illegal immigrants and narcotics. But Prince George’s Dock had been extended to accommodate 11 huge cruise ships at once.

The Chaplin House dock had a new gazebo, but otherwise looked exactly the same. Joan, a Swede and former model whom Ronnie met during a brief turn as a race car driver, walked out to greet us. “Welcome home,” she said.

Every step up the long concrete walkway from the dock was a step into the fourth dimension. When the south veranda of the old wooden bungalow came into view, I could almost see my father in his favorite dark blue nylon swim trunks, his tanned back to us, washing snorkeling gear at the tap below the railing and carefully laying it out to dry. He died 13 years ago at age 84 after a ruptured aneurysm. I had brought his ashes with me.

Born in India, where his father was a British military officer, my father had been something of a black sheep. He failed to follow his brothers into university and the family regiment, instead sailing away from England at age 27 in an ancient ketch with vague plans of circumnavigat-ing the world. He ran out of money in Barbados, crewed for my sailing uncle, who introduced him to my mother, and went ashore in Philadelphia, where she was a member in good standing of polite society.

My father’s career as an ichthyologist stemmed from a single encounter in Barbados in 1934: a six-foot barracuda that slowly turned to face him until it was a circle bisected by lips and teeth. “A pike-like fish, once recognized never forgotten,” as he put it in his Fishwatchers Guide to West Atlantic Coral Reefs, printed on waterproof paper with illustrations by British artist and conservationist Peter Scott and published in 1972. The barracuda is the wolf of the Bahamian reefs, the top of the food chain. As a child, I saw them all the time, and the powerful, undershot jaw and cold-eyed inquisitiveness never failed to remind me that I was vulnerable, out of my element, in a wilderness.

After World War II, my mother bought the house (originally the Agassiz House, after the Harvard naturalist Louis Agassiz’s son, Alexander, also a naturalist, who lived there in the 1890s), and my father’s interest began to gather steam. Once I had found my own totem—the fairy basslet—I was eager to participate in his studies. Along with my younger sister, Susan, we began collecting in tide pools, turning over rocks and scooping up with dip nets the little fish, morays, octopuses, brittle stars, sea urchins, anemones, sea slugs and other creatures that lived underneath. We set fish traps in the harbor and seined in the shallow waters of nearby mangrove creeks. We created more little worlds for the captured creatures in our living room aquarium and studied their behavior. The octopuses had a way of crawling out of it in the early hours of the morning to die under furniture.

All of this might have remained a mere hobby, but my father had a nose for new developments. Scuba gear, which Jacques Cousteau had invented during the war, enabled him to work at depths that few could reach before. And he was quick to make scientific use of an organic fish poison called rotenone, prepared from the roots of certain tropical legumes and traditionally used by the Indians of the Amazon basin to harvest fish for food. We used a water-soluble rotenone powder, which we carried in sacks and dispersed at different depths on a reef. In half an hour or so, small fish within the localized cloud would begin to surface or sink to the bottom, making it possible to describe more accurately than ever the types and numbers of fish in a given area.

A childhood friend of my mother’s, H. Radclyffe Roberts, was the Academy’s director at the time and participated in some of those early rotenone collections. He was amazed. “From the beginning, there was great difficulty in identifying all but the most common species, and soon species were found that were very rare or previously quite unknown,” Roberts wrote in his foreword to Fishes of the Bahamas. Research for the book got under way in earnest after Roberts arranged for the Academy to hire Böhlke, an ichthyologist who had just graduated from Stanford, to work with my father. My father was 48, Böhlke was 24, and I was 9, but I was never made to feel like a junior partner. In fact, my eyes were sharper than theirs, and I was able to recognize an unknown fish more quickly.

The day after I returned to Chaplin House, three scientists showed up: Dagit, now 40, an authority on a rare deep water shark relative called the ratfish; Heidi Hertler, 39, who specializes in the impact of land use on marine environments; and Danielle Kreeger, 43, who researches aquatic ecosystems. They brought photocopies of my father’s field notes. The plan was for me to try to take them back to some of our old collecting sites, and to see how the reefs had changed—and why—since I saw them 50 years earlier.

I’d never read these notes before—all in his small, neat handwriting, complete with drawings and little maps. The style was scientific, but sometimes I heard his voice:

In the stomach of the wahoo, which was otherwise empty, were two revolting living parasites. About 1 inch long, the same colour and general appearance as a newly hatched sparrow. They had long prehensile necks which could be extended another inch and which constantly weaved about in a blind but sinister manner. At the end of this neck was a mouthlike orifice. Underneath the neck on the main body was another orifice of unknown function. I placed them in a beaker of salt water where they seemed fairly happy, exuding drops of what looked like digested blood. These creatures remained alive in salt water until Feb. 21, when I placed them in alcohol.

Who would compare a revolting parasite to a newly hatched sparrow? Or take such apparent pleasure in the blind, sinister manner of their neck-weaving? Or note that they seemed “fairly happy” exuding those drops of digested blood? Only a self-taught Englishman with a quirky sense of humor who loved to read his young son ghost stories. Burying myself in his notebooks, I came to fully appreciate the range and depth of my father’s obsession for the first time.

I was holding my breath in more ways than one as the scientists and I prepared to enter the water off Lyford Cay near the western tip of New Providence Island. In the 1950s, this shallow reef was composed mainly of spectacular stands of elkhorn and staghorn coral. Great spreading branches reached 20 feet from the sandy bottom to the surface. Their color was a light, glowing terra cotta, the texture deeply serrated with the chambers of the polyps that had made them. Huge schools of bluestriped grunts hung in the branches.

“Gin clear” was how the guidebooks referred to the water, and perhaps it is even brighter in my memory. Visibility back then could be well more than 100 feet, and the element magnified and intensified rather than obscured. The reef fish seemed lighted from inside—stylish dark gray French angelfish with their downturned white mouths, yellow-ringed eyes and gold-tipped body scales; gaudily impudent young turquoise-spotted yellowtail damselfish; lazily graceful slippery dick wrasse; pony-like, dainty tangs; blue clouds of chromis. The fish, anemones, purple gorgonians, soft corals, tube sponges and sea fans all moved to a light, watery rhythm, the symphony of the reef. That was what I remembered best, the feeling of being a symphonic part of things in a way I never felt on land. “Why did man ever come out of the sea?” my father used to wonder. We’d take a few deep breaths on the surface, jackknife, and fly down into the real world.

The scientists were still fiddling with their scuba equipment, cameras, clipboards and measuring gear as I went overboard in a cloud of bubbles. When I got my bearings and could look around, it took a few moments to understand exactly what I was seeing. Finally it came to me: the light had gone out.

It was a sunny day, and plenty of light shone through the surface onto the reef. But dark green-brown algae covered the broken branches of elkhorn coral, and they no longer glowed with that magnified, intensified fluorescence. Under the algae, the coral had died.

the old familiar collection sites were as easy to find as my childhood bedroom. Sometimes, piloting our rented motorboat, I could pick out the exact same coral head. And more often than not, it would be mostly dead.

We counted fish, surveyed the bottom and took water samples. At two of my father’s old sites, the fish population had inexplicably grown; we discovered later that a local dive shop fed them to please the tourists.

At the 15 or so other sites, the story was pretty much the same. Predatory fish such as grunts, snappers and groupers appeared seriously reduced (we’ll do a more exact count in the future with rotenone), while algae-eating, coral-grazing fish such as parrots, tangs and wrasses seemed unaffected, or in some cases, had increased. The larger snappers and groupers had disappeared completely, and crawfish were scarce. We counted almost none of the rarer species such as mackerel, eagle rays, drums, filefish, toadfish, soapfish or cherubfish.

Almost every time my father and I entered the water in the 1950s, a barracuda would be there. It seemed to understand when you were scared, and it would follow you until you got out of the water, sometimes gaping its mouth, showing its teeth and shearing through the water in a blood-chilling way. But in ten days of diving and snorkeling up and down the north coast of New Providence Island, we never saw a single one. As a child I had nightmares about barracudas, but I missed them now. Their absence underlined like nothing else the fact that my father was no longer here, that everything was different. “It is the part of wisdom never to revisit a wilderness,” conservationist Aldo Leopold wrote.

Danielle Kreeger’s water samples provided the expedition’s most intriguing data. She found that large microscopic particles of suspended matter were much more prevalent “downstream,” or to the leeward end of the island of New Providence, than in other locations. An abundance of such particles can disrupt the ecological balance and indicate that algal blooms and pollution have passed the point where they can be grazed down by the filter-feeding community—corals, sponges and bivalves—leading to cloudier water.

Other researchers have also found poor water quality to be an important factor in Bahamian reef destruction. The city of Nassau pumps treated sewage more than 600 feet down into “deep injection disposal wells” in the limestone base of the island, but maintenance of the wells is sporadic, and they can develop leaks along the injection tubes.

Gordon England, a senior engineer in the Bahamian Ministry of Works and Utilities, says much of the island’s sewage goes directly into poorly constructed septic tanks that can overflow in floods. Today, demand far outstrips capacity; the local population has more than tripled since the 1950s, and tourism has grown from 244,000 visitors a year to some 4 million. Still, England says that the large particle pollutants we found at New Providence’s west end more likely come from the heavy industry and ship traffic there.

Compared with many other countries in the Caribbean, the Bahamas has generally been forward-looking in marine conservation. The government established the Caribbean’s first marine fishery reserve in 1958, restricts commercial fishing to Bahamians, and sets fishing seasons for most stocks, such as the Nassau grouper. Seven Marine Protected Areas have been designated, with more proposed, and various governmental and private commissions produce a stream of policy recommendations, studies and education programs. The main problem is insufficient enforcement. Studies in the Exuma Cays Land and Sea Park, located 35 miles southeast of Nassau, show a direct relationship between the number and size of Nassau grouper and their proximity to the patrol station, guarded by a single ranger.

Last year, Heidi Hertler and I made a second expedition to my father’s old haunts, this time with Loren Kellogg, 41, of the Academy’s ichthyology department, who is completing his doctoral thesis on groupers, and Ken Banks, 52, a coral expert with Broward County, Florida’s Environmental Protection Department. Banks’ observations backed up Kreeger’s data from the first trip: coral on the leeward side of the island was in especially bad shape, with only 7 percent of the bottom covered with live coral polyps, compared with a healthy 20 percent in an upstream location.

The closer the coral was to the island of New Providence, Banks found, the worse its condition. The worst of all was in shallow water off Clifton Point, not far from Lyford Cay, where there was a brewery, an oil-burning power plant, a pipeline to a second power plant and a deep water docking facility for ships carrying oil or other cargo. In the Lyford Cay area itself, there is much residential development.

One way to evaluate coral cover is by comparing video images taken at different times. It so happens that a Bahamian named Stuart Cove, who owns a dive shop, made a video survey of one area in early 1998. It showed the coral to be in excellent condition, whereas our own survey on this reef showed that most of the coral tissue that was alive then had died.

The coral in Cove’s video survey was mainly boulder star, a dome-shaped reef-building coral. It had apparently been bleached following 1998’s El Niño current, and it may have then been killed by algae blooms and pollution. Cove had no video survey of the elkhorn coral off Lyford Cay, now all dead except for small pockets of new growth that Banks said were “insignificant,” but he said that disease had struck heavily there too after the 1998 bleaching.

“Another dead reef,” Banks kept saying as we boated around the island. Diseased elkhorn coral is partly snowy white, then gradually turns greenish brown as algae grows over it. Brain coral with black-band disease looks like a balding head. Lacy, delicate staghorn coral is the most susceptible to diseases, and we found no living staghorn at all—only the masses of broken staghorn off Clifton Pier where big ships had dragged their anchors. When I was a boy it was everywhere.

We have some way to go before this study is complete, but we’ve determined that destruction to the reef life my father studied is widespread, that a good deal of it occurred after an El Niño year, and that the damage is worst close to developed and industrial areas that produce pollution.

My father’s aim was to discover and describe rare new species. Ours is to find out if they are still around and what might be done to save them.

The first thing I did after getting settled at the Chaplin House was to put on my snorkeling gear and swim out to the little ledge I’d dived on with my father so long ago. A small fish like the fairy basslet could live perhaps as long as 18 years. Would a great-grandchild of the original one still be in residence?

No barracudas to watch out for, but plenty of jet skis. The ledge was right where I thought it would be, about 50 feet from the house and 8 feet down. Here’s a census for the ten-foot radius around it: 3 male bluehead wrasse, 1 juvenile dusky damselfish, 4 blue runner, 1 squirrelfish, 1 juvenile Spanish hogfish, 1 creole wrasse, 1 green razorfish, 1 blackbar soldierfish, 4 juvenile queen conch, 2 long-spined sea urchins.

There was no fairy basslet. And I remember there used to be many other creatures around that ledge: cuttlefish, moray eels, octopuses, soapfish and triggerfish. At least the long-spined sea urchins I saw were a good sign. They are algae eaters and crucial to reef ecology. A mass die-off of urchins in the 1980s from a disease that spread out of the Panama Canal had been a step toward disaster. With the population of grazing fish reduced by years of overfishing, the urchin die-off left algae free to flourish.

My father’s favorite collecting station in the Bahamas was a spectacular coral head towering from a white sand bottom 50 feet down to within 10 feet of the surface. The head is located about five miles from the Chaplin House, on the ocean side of a little uninhabited cay east of Nassau.

On the sand flats near the head, Jim Böhlke found and was the first to describe a new species of eel, Nystactichthys halis, which he informally called the garden eel because a colony of them looked like a living garden, appearing to grow from the sand like plants and swaying gently in the current. To me, the name was appropriate to the whole place: a garden under the sea.

After the Academy scientists had departed, I took my father’s ashes out to that coral head and let them form a cloud in midwater. I watched them slowly descend through the blue space around the spire. Then I dove down through the cloud and touched the coral that was still alive. My father always believed in the supreme power of nature to maintain things as they should be. He probably would have attributed the decline of the reefs to a cycle that will eventually reverse itself. But his legacy might well teach us a more somber lesson.