A Wildlife Mystery in Vietnam

The discovery of the saola alerted scientists to the strange diversity of Southeast Asia’s threatened forests

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/saola_aug08_631.jpg)

A landslide has blocked the cliff-hugging road into the Pu Mat National Park in northwestern Vietnam. To go farther, we must abandon our car and wade across a shallow river. My wife, Mutsumi, a photojournalist, and I roll up our jeans to the knee and look uncertainly at our two young boys. Do Tuoc, a 63-year-old forest ecologist, reads our minds. "I'll take the bigger boy," he says, hoisting our 6-year-old onto his shoulders.

Before I can come to my senses and protest, Tuoc plunges into the current, sure-footed, and reaches the opposite bank safely. I wade out with our 3-year-old clinging to my neck. I stumble like a newborn giraffe on the slippery rocks of the riverbed. My jeans are soaked. My son, asphyxiating me, crows with joy. Both boys want to do it again.

I shouldn't have been surprised by Tuoc's nimbleness: he knows this primeval wilderness better, perhaps, than any other scientist. It was near here in 1992 that Tuoc discovered the first large mammal new to science in more than half a century, a curious cousin of cattle called the saola. The sensational debut showed that our planet can still keep a fairly big secret, and it offered a reprieve from the barrage of bad news about the state of the environment.

If only humans had reciprocated and offered the saola a reprieve. A decade after coming to light, the unusual ungulate is skidding toward extinction. Its habitat in Vietnam and Laos is disappearing as human settlements eat into the forest, and it is inadvertently being killed by hunters. Saola appear to be particularly vulnerable to wire snares, introduced in the mid-1990s to snag Asiatic black bears and Malayan sun bears, whose gallbladders are used in traditional Chinese medicine. For the saola, "the situation is desperate," says Barney Long, a World Wildlife Fund conservation biologist, who is working with local scientists to protect forests in central Vietnam inhabited by saola. The Vietnamese government created Pu Mat and nearby Vu Quang national parks in response to the saola discovery, and this past fall designated two more nature reserves in the saola's dwindling range and banned all hunting in critical saola habitat. Neighboring Laos, the only other country in which the saola has been spotted, has pledged similar action. But no one knows whether these eleventh-hour efforts will succeed.

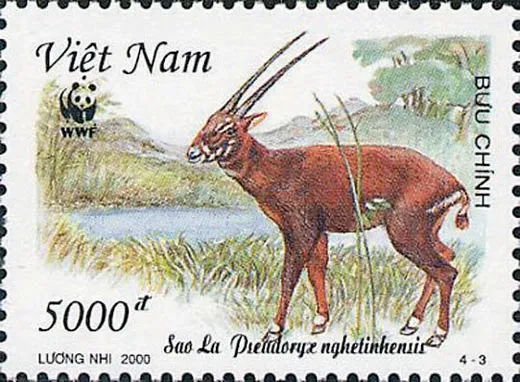

That's because the saola is so rare that not even Tuoc has spied one in the wild. Estimates of their numbers are based on interviews with villagers who have glimpsed the animal, and on trophies. Tuoc, who works for the Forest Inventory and Planning Institute in Hanoi, first beheld a partial saola skull mounted in a hunter's home in Vu Quang. He knew he was seeing something extraordinary. DNA tests confirmed that the saola was a previously unknown species, the first large mammal discovered since the kouprey, a Southeast Asian forest ox identified in 1937. The saola's horns, one to two feet in length and slightly diverging, inspired its name, which means "spinning wheel posts."

Tuoc calls himself "very lucky" to have discovered the saola—and to be alive. Forty years ago, his older brother volunteered in the Vietnam People's Navy, which ran supplies to forces in the south on a sea version of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. His brother's service exempted Tuoc from the military and allowed him to focus on science. With his keen powers of observation, he has discovered two other species in addition to the saola.

The best guess is that a couple of hundred saolas are left in Vietnam, Long says. "Very little is known about the saola. We don't know exactly where it occurs, or how many there are. There's a big question mark surrounding it," says Laos-based William Robichaud, who is leading a working group of the International Union for Conservation of Nature that met in June to draft a strategy for protecting saola. "The last incontrovertible evidence we have—a photograph from a camera trap—was in 1999," says Robichaud.

Since February, Robichaud and his staff have placed about 20 camera traps in Laos' Nakai-Nam Theun National Protected Area—historical saola habitat, according to hunters' sightings. But neither the cameras nor interviews with locals have yielded evidence of saola activity. "Villagers seem unsure if it's still hanging on or not," he says.

Robichaud is one of the few scientists who have observed a live saola. In early 1996, an adult female was captured and sold to a zoo in central Laos. "She was a remarkable animal," he says. Nicknamed "Martha," she stood about waist high, her 18-inch horns sweeping back over her neck. Although the saola's closest relatives are cows and bison, it resembles a diminutive antelope. It has coarse, chestnut-brown hair and a thick, white streak above its eyes. Its anatomical claim to fame is massive scent glands bulging from its cheeks. Martha would flare a fleshy flap covering a gland and dab a pungent green musk on rocks to mark her territory.

Robichaud says he was most fascinated by Martha's calmness. A few days after her arrival at the zoo, she ate from a keeper's hand and allowed people to stroke her. "The saola was tamer and more approachable than any domestic livestock I've ever been around," he says. "You can't pet a village pig or cow." The only thing sure to spook a saola is a dog: one whiff of a canine and it crouches low, snorting and tilting its head forward as if preparing to spear the enemy. (Saolas are presumably preyed upon by dholes, or Asiatic wild dogs, common predators in saola territory.) Remove the threat, though, and the saola regains the Zen-like composure that in Laos has earned it the nickname "the polite animal."

Martha's equanimity around people may have been genuine, but she died just 18 days after her capture. It was then that zookeepers discovered that she had been pregnant. But they could not determine her cause of death. The handful of other saolas that have been taken into captivity also perished quickly. In June 1993, hunters turned over two young saola to Tuoc and his colleagues in Hanoi. Within months, the pair succumbed to infections.

The saola's baffling fragility underscores how little is known about its biology or evolutionary history. Robichaud and conservation biologist Robert Timmins have proposed that saola were once widespread in the wet evergreen forests that covered Southeast Asia until several million years ago. These forests receded during cool, dry ice ages, leaving just a few patches suitable for saola. "If we leave the saola alone," says Tuoc, "I think—no, I hope—it will survive."

Other scientists argue for hands-on assistance. Pierre Comizzoli of the Smithsonian's Center for Species Survival says a captive breeding program is the only option left to save the saola from extinction. He teamed up with scientists from the Vietnamese Academy of Science and Technology in Hanoi on a survey late last year to find possible locations for a breeding site.

"It's a sensitive topic," he acknowledges. "But captive breeding doesn't mean that we are going to put saolas in cages, or do industrial production of saolas." Instead, he envisions putting an electric fence around a select swath of saola habitat, perhaps half an acre. "They would have access to their natural environment and could feed themselves, and at the same time we could start to study them," says Comizzoli, adding that something as simple as fresh dung would be "fantastic" for research purposes.

After fording the river, Tuoc and my family and I hike to a ranger station. The next leg of our journey is on motorcycles. Their make, Minsk, is emblazoned in Cyrillic on the gas tank. Our sons, sandwiched between my wife and a ranger, have never ridden a motorcycle before, and they squeal with delight. For several miles, we tear uphill on an empty, curvy road faster than this anxious parent would like. At the end of the road, we hike into the misty hills on our quest to spot a saola.

Preserving this habitat will help a host of other rare creatures, including the two other new mammals in Vietnam that Tuoc helped uncover, both primitive kinds of deer: the large-antlered muntjac, in 1994, and the diminutive Truong Son muntjac, in 1997. Strange beasts continue to emerge from these forests, including the kha-nyou, a rodent identified in 2006 as a species thought to have been extinct for 11 million years. "If we lose the saola," says Long, "it will be a symbol of our failure to protect this unique ecosystem."

At Pu Mat, the late morning sun is burning off the mist. With the spry Tuoc leading the way, we clamber up a slick path until we reach Kem Waterfall. Tuoc grabs a handful of broad, dark-green leaves near the entrancing falls. "Saola like to eat these," he says. "At least, we have seen bite marks." These Araceae leaves, I realize with a pang, may be as close as I ever get to a saola. Tuoc, too, has no delusions. "Maybe I'll never see one in the wild," he says.

Richard Stone is the Asia editor for Science magazine. He lives in Beijing.