Adventures In Laser Science

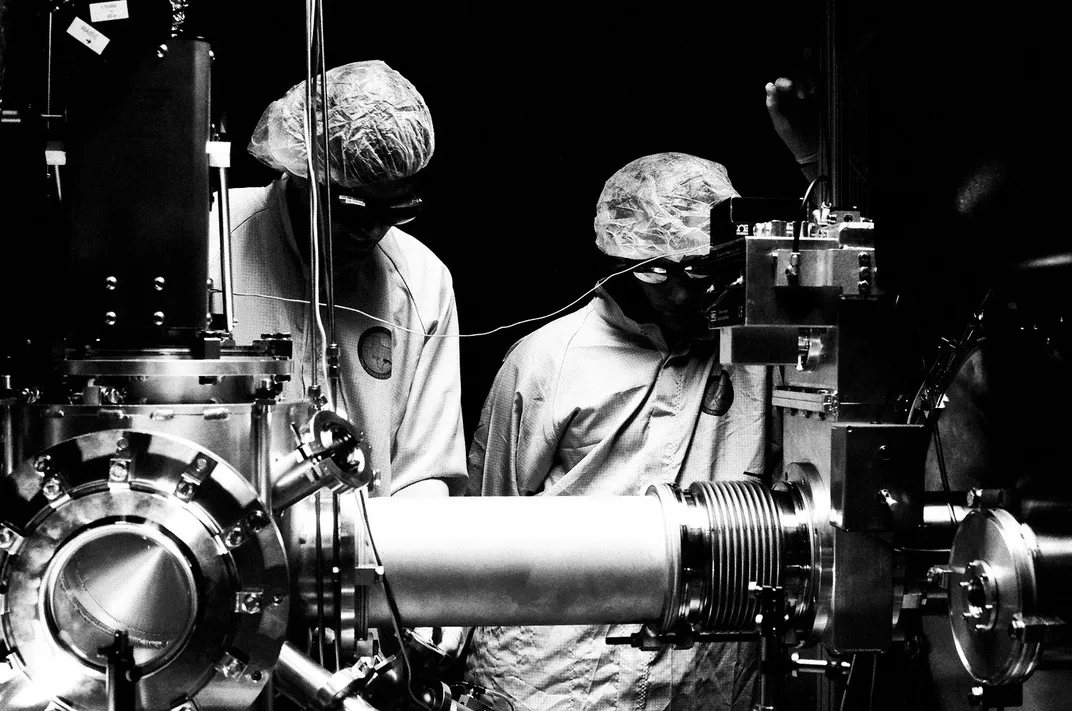

A photo series by Austin-based photographer Robert Shults casts physicists and their everyday life in the lab in a sci-fi B-movie light

Scientists are rarely heroes in the fictional universe. In fact, more often than not they're the villains or antiheroes on the verge of insanity. Take Doctor Frankenstein, for example, from Mary Shelley's 1818 classic, or Robert Louis Stevenson's Dr. Jekyll—or even Doc Octopus, of Marvel comic book fame.

Photographer Robert Shults wants to turn the mad scientist trope on its head with a series of photographs that casts everyday physicists as the guys and gals that save the day. His story begins at the University of Texas in Austin in 2008. Shults was teaching a photography workshop at the time, and he happened to meet a friend of a friend who worked in a campus laboratory called the Center for High Energy Density Science. The federally funded lab in the bowels of the physics building is encased by lead, concrete and steel and houses a petawatt laser, which can produce, for a fraction of a second, more power than the entire U.S. electrical grid.

A petawatt laser works on the same basic principles as the lasers found in home printers or laser pointers: it amplifies a beam of light. Starting with a very weak pulse of light (one billionth of a joule), the laser amplifies this one hundred billion times to about 200 joules—equivalent to a normal lightbulb running a few seconds. Except that they pack that energy into a tenth of a trillionth of a second to create one of the brightest lights in the universe.

Scientists can use the beam to accelerate particles—something they do, for instance, to make high-energy protons for use in cancer therapies or to create neutrons that, when passed through materials, can determine whether they're corroded. But, perhaps the most mind-blowing experiments conducted in the University of Texas lab involve astrophysical models. The light that the laser produces is comparable to really intense environments in the universe, such as the center of a star or the area in close proximity to a black hole.

“You can take this very intense pulse of light and then strike something and create a very extreme state of matter,” says Todd Ditmire, who directs the lab. “It’s like bringing a star to Earth.”

As a kid, Shults watched NASA liftoffs and loved the science fiction worlds of Star Wars and Star Trek. “Literally ever since I was a child I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t completely fascinated with the exploration of outer space,” he says.

Perhaps for this reason, Shults has always been intrigued by physics. Photographers and physicists, actually, draw on the same basic tools: light, space and optics. When he saw the laser in action, he knew it had to be the subject of his next photography project. “We can’t fly out to the middle of space to see this stuff, but they can use light to bring it here,” says Shults. “That to me is the most fascinating thing I’ve seen in my life.”

Over nine months, Shults shadowed scientists working with the laser. At the time, the facility had just opened, so much of what they were doing involved tweaking instruments. Because lab work doesn't generally make for great action shots, Shults spent many of his days watching scientists walk back and forth from one end of the laser to another making tiny adjustments to optical instruments. The photographer wanted to convey the vital nature of these mundane actions.

“My job is to impart to a viewer what being in the facility and interacting with this device feels like,” says Shults. “And it certainly feels much more grand and dramatic than it probably looks.”

Using an analog rangefinder camera, he shot on high contrast black and white film (1600 ASA) to give his photographs a fine-grained appearance. Creating this visual drama was part effect and part necessity. "It’s not a normal place to take photographs," says Shults. A direct shot of laser light can fry the light sensors in a digital camera. Though laser light can burn a hole in film, with film Shults could just click through to the next film frame, instead of having to replace an entire digital camera in the off chance that he accidentally took a direct shot of the beam.

Coincidentally, the laser room itself had to be shrouded in darkness to view the beam through infrared instruments, and the flashes of laser light in this dark environment only played up the drama. The light becomes a character in the lab, as Ditmire puts it, bouncing off both the equipment and the scientists manipulating it. And, it was this lighting effect that Shults was looking to capture.

The resulting images evoke the science fiction movies of his childhood, with a kind of film noir-esque mystery. Typically presented without captions, they invite the viewer to imagine a storyline driving the images of the scientists-turned-superheroes. Shults calls the series "The Superlative Light," both in reference to the high quality of the laser itself and a theology essay by philosopher Catherine Pickstock—Pickstock uses the phrase to describe the continual creativity of a deity figure.

Shults wanted to portray, in a sense, the intersection of fact and fiction. On one level, the photographs document the reality of scientists working in a lab, but because of the way they're constructed, they also capture the fantastical nature of the scientists' experiments. Shults plays with the idea that although we take photography to be a truthful means of conveying reality, photographs can also be a deliberately engineered medium perfect for lending images a sense of fantasy.

This month, Shults raised $23,841 in a Kickstarter campaign to help fund the publication of a book, to be released this fall by Daylight Books, a non-profit art and photography publisher. Instead of the traditional, sometimes stuffy art criticism essay that precedes most photo books, he has enlisted Ditmire to write an explanation of the science conducted at the University of Texas lab. The book will also include a story to go along with the images, penned by Rudy Rucker, a mathematician and author.

The publisher plans to bind the book using the head-to-tail binding of old two-in-one sci-fi books—where readers could read one novel front to back, and then flip the book over and read a different story back to front. Each reader can have a different experience, whether they start reading Ditmire's scientific text or Rucker's sci-fi story. Shults hopes this playful format will “augment the fiction and nonfiction of the whole thing, the science and the art of it, the imagination and the discipline.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/28/29/282990a3-a0d0-4455-8428-b0f0fba7934a/25400037-edit.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)