Alan Dudley’s Wondrous Array of Animal Skulls

A new book delivers fascinating photographs of over 300 skulls from the British taxidermist’s personal collection—the largest in the world

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20121101125754Black-headed-spider-monkey-web.jpg)

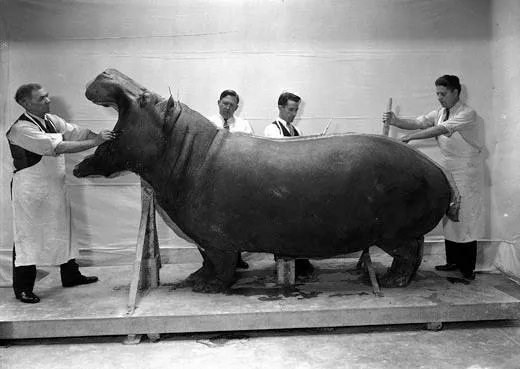

Alan Dudley is obsessed with skulls. At the age of 18, he found a fox carcass near his home, skinned the animal and prepared its skull for museum-like display. “His single fox became a fox and a bat; then a fox and a bat and a newt; then fox, bat, newt, anteater, owl, cuckoo, monkey; and on and on,” writes Simon Winchester, a bestselling author, in a new book.

The 55-year-old taxidermist now has more than 2,000 skulls in glass cases and mounted to walls in his home in Coventry, England. His personal collection, thought to be the largest and most comprehensive in the world, is only growing, as he continues to acquire specimens from zoos and dealers. A penguin. A red-bellied piranha. A giraffe. “You name it, I’ve got it, I’ll take any skull—as long as it’s not human,” Dudley recently told the Daily Mail.

In a new book, Skulls, Winchester shares Dudley’s curious collection with the public. With some input from the British collector, he selected more than 300 skulls—from mammals, birds, reptiles, fish and amphibians—with the aim of presenting “as representative a cross section of the vertebrate universe as was possible.” Photographer Nick Mann captures these skulls from several angles, so that readers can view them as if they were turning them in their own hands.

The skulls are exceptional educational pieces. Dudley’s preparation of the skulls preserves them in fine detail. He soaks each one in a bucket of cold water for weeks to months. “The blood vessels, the bands of cartilage and clumps of muscle, as well as the eyes and tongue and soft palate and hearing mechanisms, all vanish, and what remains is an off-white amassment of curvilinear bones, some hard and some soft, some massive and some delicate,” writes Winchester, in Skulls. He then washes the skull, whitens it with hydrogen peroxide and applies a thin coat of varnish.

Skulls naturally accentuate the toothiness of wild animals; some of the fangs are quite menacing. But, overall, the collection conveys a sense of beauty, rather than horror.

I think Winchester puts it best. “Perhaps no other biological entity retains such a grip on human psychology as does this assemblage of hollow bone, this thing of domes and sockets and jaws and of mysterious interior passageways and canals,” he writes.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)