An Explanation for the Missing Sunspots

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20110520104113sun.jpg)

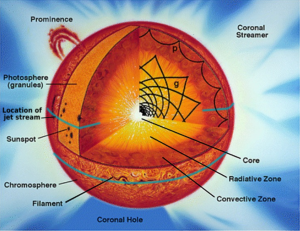

I bet that most of you don’t know that the sunspots are missing. That’s okay. I’m sure many people don’t realize that the sun is more than just a ball of fire: it has a complex internal structure, features that vary based on multi-year cycles, and it can create solar storms that knock out power and communication here on Earth. And sometimes it behaves in ways that scientists still don’t understand well.

Sunspots are areas of intense magnetic activity on the surface of the sun. They look like dark spots to us because they are around a thousand degrees cooler than the area around them. At 4,000 to 4,500 degrees Kelvin (about 7,000 degrees Fahrenheit), though, they’re still incredibly hot. Sunspot activity cycles about every 11 years, and scientists had expected the sun to start the next cycle of heightened activity, Cycle 24, in late 2007 or 2008. Some early forecasts predicted that Cycle 24 would be especially active.

But then the sun stayed quiet—in the solar cycle’s minimum phase—for one to two years longer than expected. There hasn’t been a significant solar flare in the last two years. There had even been talk about whether we might be entering another “Maunder Minimum,” the period in the late 17th- to early 18th-century when there were only a few sunspots, compared to thousands normally, and that coincided with the Little Ice Age. That worry, at least, seems to be unfounded, as NOAA has now seen indications that Cycle 24 is nearly ready to begin, though it will likely be less active than average.

And now we have some clues about why the sun was quiet for so long. Solar scientists led by Frank Hill of the National Solar Observatory announced yesterday at a meeting in Boulder, Colorado, that the delay in the cycle start is associated with a solar jet stream deep below the sun’s surface.

These jet streams (one in the northern hemisphere, one in the south) originate at the sun’s poles, a new one every 11 years. Over the next 17 years, the jet streams migrate towards the equator, and when they reach a critical latitude of 22 degrees, they are associated with the production of sunspots. Scientists here on Earth can track these jet streams through the ripples on the sun created by the sound within, Hill said.

However, the jet streams that would be associated with Cycle 24 are a bit sluggish, taking three years to cover 10 degrees in latitude instead of the normal two years. “The flow for this cycle is taking much more time to move down to the critical latitude,” Hill said. But now that the jet streams have reached that latitude, the cycle should start right up.

Hill doesn’t know if the jet streams are a cause of the sunspot cycle or a consequence of it, though he leans towards cause. And though he says that the sluggishness was the result of other things going on under the surface of the sun, he can’t name what those things would be. “We do not fully understand the interplay of the dynamics under the surface of the sun,” he said.

I guess there’s plenty of mystery left, then, to keep the solar scientists busy.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)