Ancient DNA Reveals Complex Story of Human Migration Between Siberia and North America

Two studies greatly increase the amount of information we have about the peoples who first populated North America—from the Arctic to the Southwest U.S.

:focal(915x712:916x713)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4f/f0/4ff0ffdf-4239-40a0-93d5-6c3ec5dbd899/202468.jpg)

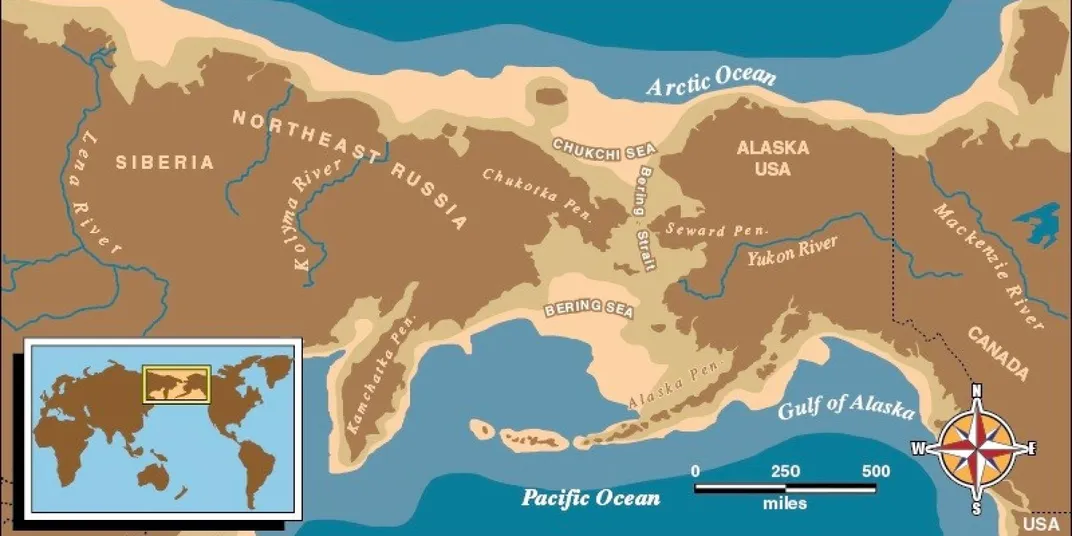

There is plenty of evidence to suggest that humans migrated to the North American continent via Beringia, a land mass that once bridged the sea between what is now Siberia and Alaska. But exactly who crossed, or recrossed, and who survived as ancestors of today’s Native Americans has been a matter of long debate.

Two new DNA studies sourced from rare fossils on both sides of the Bering Strait help write new chapters in the stories of these prehistoric peoples.

The first study delves into the genetics of North American peoples, the Paleo-Eskimos (some of the earliest people to populate the Arctic) and their descendants. “[The research] focuses on the populations living in the past and today in northern North America, and it shows interesting links between Na-Dene speakers with both the first peoples to migrate into the Americas and Paleo-Eskimo peoples,” Anne Stone, an anthropological geneticist at Arizona State University who assessed both studies for Nature, says via email.

Beringia had formed by about 34,000 years ago, and the first mammoth-hunting humans crossed it more than 15,000 years ago and perhaps far earlier. A later, major migration some 5,000 years ago by people known as Paleo-Eskimos spread out across many regions of the American Arctic and Greenland. But whether they are direct ancestors of today’s Eskimo-Aleut and Na-Dene speaking peoples, or if they were displaced by a later migration of the Neo-Eskimos, or Thule people, about 800 years ago, has remained something of a mystery.

An international team studied the remains of 48 ancient humans from the region, as well as 93 living Alaskan Iñupiat and West Siberian peoples. Their work not only added to the relatively small number of ancient genomes from the region, but it also attempted to fit all the data together into a single population model.

The findings reveal that both ancient and modern peoples in the American Arctic and Siberia inherited many of their genes from Paleo-Eskimos. Descendants of this ancient population include the Yup’ik, Inuit, Aleuts and Na-Dene language speakers from Alaska and Northern Canada all the way to the Southwest United States. The findings stand in contrast to other genetic studies that had suggested the Paleo-Eskimos were an isolated people who vanished after some 4,000 years.

"For the last seven years, there has been a debate about whether Paleo-Eskimos contributed genetically to people living in North America today; our study resolves this debate and furthermore supports the theory that Paleo-Eskimos spread Na-Dene languages," co-author David Reich of Harvard Medical School and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute says in a press release.

The second study focused on Asian lineages, Stone notes. “The study is exciting because it gives us insight into the population dynamics, over 30-plus thousand years, that have occurred in northeastern Siberia. And these insights, of course, also provide information about the people who migrated to the Americas.”

Researchers retrieved genetic samples for 34 individuals’ remains in Siberia, dating from 600 to 31,600 years old. The latter are the oldest human remains known in the region, and they revealed a previously unknown group of Siberians. The DNA of one Siberian individual, about 10,000 years old, shows more genetic resemblance to Native Americans than any other remains found outside of the Americas.

Fifteen years ago scientists unearthed a 31,000-year-old site along Russia’s Yana River, well north of the Arctic Circle, with ancient animal bones, ivory and stone tools. But two tiny, children’s milk teeth are the only human remains recovered from the Ice Age site—and they yielded the only human genome yet known from people who lived in northeastern Siberia during the period before the Last Glacial Maximum. They represent a previously unrecognized population that the study’s international team of authors have dubbed “Ancient North Siberians.”

The authors suggest that during the Last Glacial Maximum (26,500 to 19,000 years ago) some of these 500 or so Siberians sought more habitable climes in southern Beringia. Stone says the migration illustrates the ways that shifting climate impacted ancient population dynamics. “I do think that the refugia during the Last Glacial Maximum were important,” she says. “As populations moved to refugia, likely following the animals they hunted and to take advantage of the plants they gathered as those distributions shifted south, this resulted in population interactions and changes. These populations then expanded out of the refugia as the climate warmed and these climate dynamics likely affected population around the world.”

In this case, the Ancient North Siberians arrived in Beringia and likely mixed with migrating peoples from East Asia. Their population eventually gave rise to both the First Peoples of North America and other lineages that dispersed through Siberia.

David Meltzer, an anthropologist at Southern Methodist University and coauthor of the new study, says when the Yana River site was discovered, the artifacts were said to look like the distinctive stone tools (specifically projectile “points”) of the Clovis culture—an early Native American population that lived in present-day New Mexico about 13,000 years ago. But the observation was greeted with skepticism because Yana was separated from America’s Clovis sites by 18,000 years, many hundreds of miles, and even the glaciers of the last Ice Age.

It seemed more likely that different populations simply made similar stone points in different places and times. “The odd thing is, now as it turns out, they were related,” Meltzer says. “It’s kind of cool. It doesn’t change the fact that there’s no direct historical descent in terms of the artifacts, but it does tell us that there was this population floating around in far northern Russia 31,000 years ago whose descendants contributed a bit of DNA to Native Americans.”

The finding isn’t particularly surprising given that at least some Native American ancestors have long been thought to hail from the Siberian region. But details that seemed unknowable are now coming to light after thousands of years. For example, the Ancient North Siberian peoples also appear to be ancestral to the Mal’ta individual (dated to 24,000 years ago) from the Lake Baikal region of southern Russia, a population that showed a slice of European roots—and from whom Native Americans, in turn, derived some 40 percent of their ancestry.

“It’s making its way to Native Americans,” Meltzer says of the ancient Yana genome, “but it’s doing so through various other populations that come and go on the Siberian landscape over the course of the Ice Age. Every genome that we get right now is telling us a lot of things that we didn’t know because ancient genomes in America and in Siberia from the Ice Age are rare.”

A more modern genome from 10,000-year-old remains found near Siberia’s Kolyma River evidences a DNA mix of East Asian and Ancient North Siberian lineages similar to that seen in Native American populations—a much closer match than any others found outside of North America. This finding, and others from both studies, serve as reminders that the tale of human admixture and migration in the Arctic wasn’t a one-way street.

“There’s absolutely nothing about the Bering land bridge that says you can’t go both ways,” Meltzer says. “It was open, relatively flat, no glaciers—it wasn’t like you wander through and the door closes behind you and you’re trapped in America. So there’s no reason to doubt that the Bering land bridge was trafficking humans in both directions during the Pleistocene. The idea of going back to Asia is a big deal for us, but they had no clue. They didn’t think they were going between continents. They were just moving around a large land mass.”