Ancient Whale Fossil Helps Detail How the Mammals Took From Land to Sea

A 39-million-year-old whale with floppy feet, which may not have been very good for walking, helps illuminate the massive animals’ transition to the oceans

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/50/4b/504be92e-dc44-4b71-b119-a2dc12adb5a3/gettyimages-1192892125.jpg)

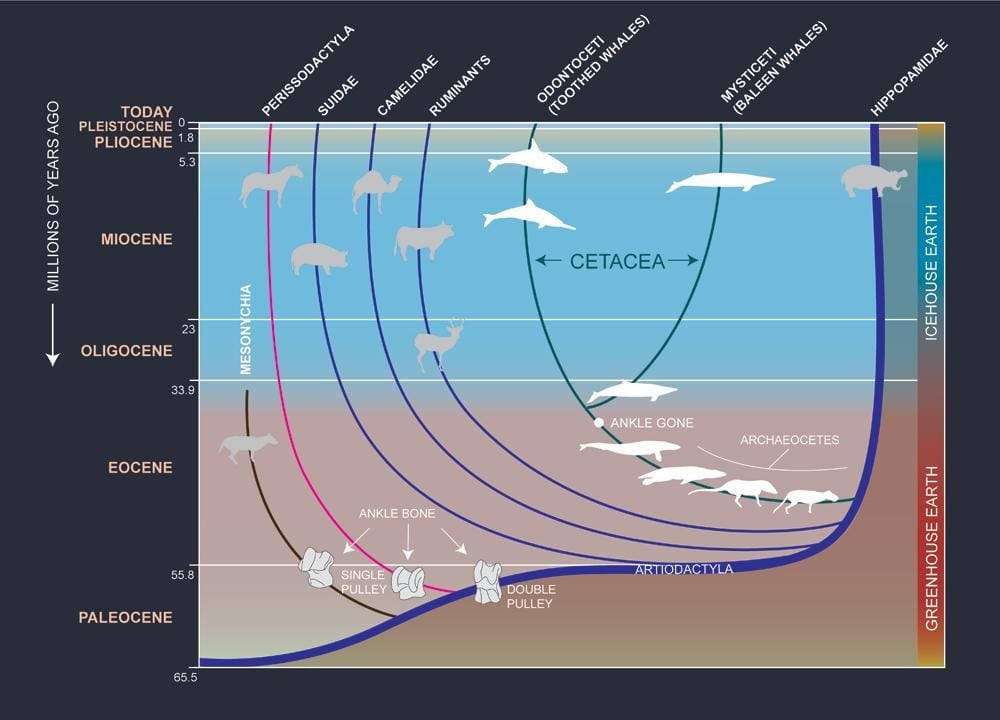

Whales don’t swim like fish do. Instead of moving their tales side-to-side like a shark or a sunfish, the marine mammals pump their tails up-and-down to propel themselves forward. But over 50 million years ago, the earliest whales had legs and could walk on land. Adapting to life in the sea required a new way of moving, and a fossil uncovered in Egypt helps estimate the time when whales became primarily tail-powered swimmers.

The partial skeleton, described today by University of Michigan paleontologist Iyad Zalmout and colleagues in PLOS ONE, is an ancient whale that swam the seas of what’s now Egypt around 39 million years ago. The fossil was found in the desert of Wadi Al-Hitan, a place so rich in cetacean fossils that it’s known as Whale Valley.

In 2007 a joint expedition between paleontologists from the University of Michigan and the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency set out to find new whales and other vertebrates in a part of Wadi Al-Hitan that had not been thoroughly explored before. “One paleontologist spotted a cluster of vertebrae weathering out from the foothill of a prominent plateau known as Qaret Gehannam,” Zalmout says, and even more fossilized bones appeared to be going into the rock. The experts had arrived at just the right time to catch the whale, recently exposed by the weathering of the foothill.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/80/7d/807dc769-01fe-4ba2-91a0-f3f0bee79c2f/dscn3231.jpg)

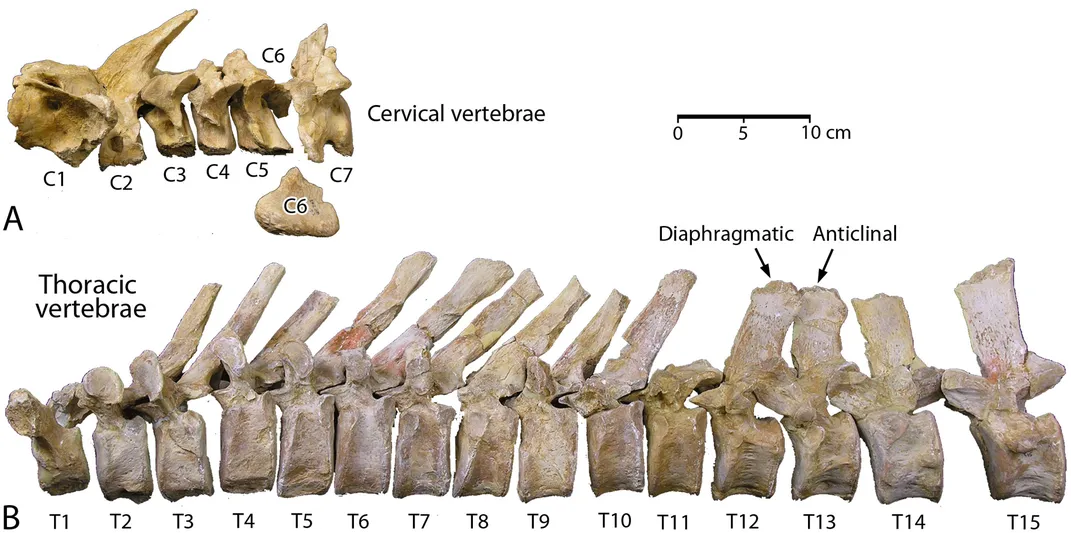

All told, the paleontologists uncovered almost the entire spine, part of the skull, and pieces of the arms and legs. “It was very clear from the shape and the size of the vertebrae and appendages that this whale is new in this area,” Zalmout says. Further study indicated that the mammal was a species not seen anywhere else in the world.

Named Aegicetus gehennae, the ancient swimmer stands out from others found in Wadi Al-Hitan, which fall into one of two groups. Some earlier whales could swim with a combination of paddling limbs and undulating their spines, not unlike otters. Other whales, like Basilosaurus, lived in the sea full time and swam with tails only. Aegicetus fits between the two, representing a moment when whales were just switching to exclusively tail-driven locomotion.

“I’d say this fossil is another excellent piece of the puzzle of the lineage of whales that went from terrestrial to fully aquatic,” says George Mason University paleontologist Mark Uhen.

Like most animals, early whale evolution doesn’t represent a straight line of progress, but instead is a branching bush of species that had various levels of aquatic skill. Many of these forms were amphibious, and, ultimately, went extinct. Another subset became more and more aquatic, sprouting its own branches that eventually spun off the first cetaceans to live in the seas for their entire lives. Aegicetus is part of the family that increasingly spent time in the water, related to today’s leviathans.

The key feature in this fossil, Zalmout and co-authors point out, is the relationship between the hips and the spine. The earliest whales had hips attached to the spine, just like any terrestrial mammal. This configuration helped the hind limbs support the animal’s weight on land. But in Aegicetus and other whales that came later, the hips are decoupled from the spine and suspended by the flesh of the body. The tight fusion of vertebrae at the hip-spine connection—called the sacrum—also became unfused and more flexible. These whales could no longer paddle with their legs and relied more on undulating their spines to move through the water. The shift indicates two things: that these whales were spending most, if not all, of their time in the water where weight-supporting legs weren’t needed, and that these beasts swam by principally using their tails.

Not that Aegicetus was much like a modern orca or sperm whale. The fossil whale, which weighed almost a ton (or about a sixth the weight of the biggest orcas), still had jaws set with different types of teeth instead of the simple cones of today’s dolphins. Nor did Aegicetus swim just like its living relatives.

“Modern whales use their tails to swim and have evolved vertebral columns, as well as back and abdominal muscles, to power the tail,” Uhen says. Aegicetus didn’t have these anatomical features, and it lacks the skeletal specializations to support a broad tail fluke. Instead, the whale probably swam in a way that would look strange to us, undulating its midsection and long tail while steering with the forelimbs, a creature right at the crux of a stunning evolutionary transformation.

“Every time we find a complete and articulated whale of a new species there would be more thinking and digging than before,” Zalmout says. While new discoveries have brought the early history of whales into greater focus than ever before, mysteries remain. For every question a fossil answers, more arise, “which keeps our lives interesting!” Uhen says. Aegicetus is now a part of that story, leading paleontologists to wonder what else may rise from the depths of the fossil record.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)