Animal Specimens, From Fish to Birds to Mammals, Get Inked

Inspired by Japanese fish rubbings, two University of Texas biologists make spectacular prints of a variety of species at different stages of decay

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20131029123018horseshoe-crab-Inked-Animal-project-web.jpg)

Adam Cohen and Ben Labay are surrounded by thousands of fish specimens, all preserved in jars of alcohol and formalin. At the Texas Natural Science Center at the University of Texas in Austin, the two fish biologists are charged with documenting the occurrences of different freshwater fish species in their home state and those neighboring it.

That is their day job, at least.

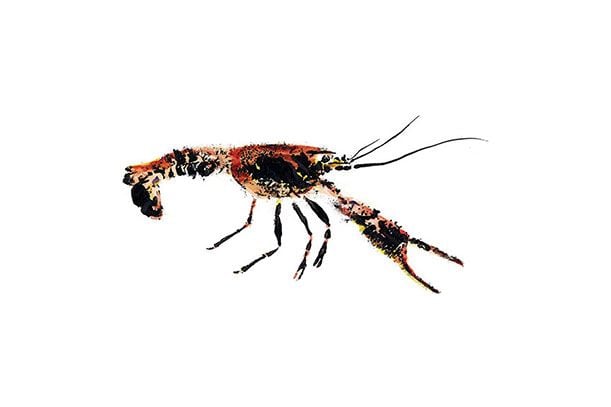

Outside of work, Cohen and Labay have teamed up on an artistic venture they call the Inked Animal Project. Since 2008, the colleagues have made surprisingly tasteful prints of actual animal carcasses—scales, fur, feathers and all.

Both scientists have dabbled in art—drawing, painting and sculpting—for as long as they can remember. As a kid, Cohen even used an octopus and flying fish that he bought at an Asian market as huge stamps to make ink patterns on paper. Fish, of course, were a natural subject for two ichthyologists, but Cohen and Labay were also familiar with a Japanese art form called Gyotaku (meaning “fish rubbing”), where artists slather ink on fresh fish and press them onto paper as a means of recording the size and other details of the catch.

Their first collaboration was a poster with prints of all ten sunfish species that live in Texas, and the Inked Animal Project was born. They inked trout, bass and catfish. But why stop with fish? The duo quickly expanded its repertoire, applying the same printmaking technique to mice, squirrels, rabbits, geese, gulls, hummingbirds and a smattering of deer, pig and cow skulls. No specimen seems to fluster the artists.

I interviewed Inked Animal’s creators by email to learn more about where they obtain their portrait subjects, how they produce the prints and what exactly possesses them to do this.

As you know, Gyotaku is both an art form and a method of scientific documentation. Are there certain anatomical traits you try to accentuate in your Inked Animal prints for scientific purposes?

Ben: I don’t think we print for any tangible scientific goal, though we do print in a spirit of documentation, similar to goals of the original Gyotaku printings I guess. As we’ve expanded our medium beyond fish, we’ve been interested in trying to document life processes through the animals, such as internal or unique anatomy and “road-kill” or animated postures.

Adam: Not long ago I ran across some field notes belonging to a fish collector from the late 1800s, Edgar Mearns, who, rather than preserving a particularly large fish, decided to trace the animal on paper and insert it in his fieldbook. We were well into the Inked Animal Project at that point and that‘s when I realized what we were really doing was a form of documentation as well as art. But, in reality, these days with cameras so ubiquitous, there is little need to print or trace the animal on paper for documentation purposes. I think our prints have relatively little scientific value, but substantial artistic value. I often think about the physical characteristics that someone who knows the species well would need to see to verify the identity of the specimen, but I try not to let that get in the way of creating interesting art. I’d much rather have interesting art of an unknown and unverifiable species.

How do you collect the animals you print?

Adam and Ben: We get the animals in all sorts of ways. In the beginning we went fishing in our spare time. Recently, as word of our project got out, we’ve had people donate specimens. A lot of our friends are biologists, hunters, exterminators and people who work in animal rehabilitation; they have access to animals and are excited to donate to the cause. Additionally, there are a lot of great animals to print that can be purchased through exotic Asian grocery stores. We’re getting serious about printing larger animals, like farm livestock. We would love to get an ostrich or emu too.

On your website, you say, “Our tolerance for gross is very high.” Can you give an example of a specimen that pushed this tolerance to its limits?

Ben: My personal worst was the armadillo. We’ve had worse-smelling animals like a gray fox that was sitting in a bucket for a full day before we printed. But something about working with the armadillo really grossed me out, almost to the point of vomiting. Most mammals are squishy with decay, but the armadillo was a stiff football of dense rotten meat. It’s also a bizarre animal that we don’t ever expect to get so intimate with. This is just a crazy theory, but animals like the Eastern cottontail or gray fox are more familiar, and maybe more approachable or acceptable when rotten. When it comes to larger, strictly wild animals, things get more interesting and intense.

Adam: Ben mentioned a gray fox that we printed in the early days of Inked Animal. I remember picking it up and the juices ran down my arm. But I was so excited by the print we were getting, which I think was the first time we realized that we were on to something really unique, that I hardly even thought about it. We recently printed a very rotten deer whose skin peeled away as we lifted the cloth to reveal a writhing mass of maggots—that was pretty gross too.

You are almost more interested in prints of dismembered, rotting or partially dissected specimens, right? Why is this?

Ben: When we started to expand from fish to other types of animals, Adam and I felt excited about not just doing something unique, but doing art that was deeper than just a pretty picture. I think we both feel that there is something indescribable about the animal prints, which allows people to view them from different vantage points. You see it as an animal print, and also as a process. I like the idea of documenting rotting or dissected animals because it emphasizes the process part of the experience. People see it and can immediately imagine what must have happened to produce the image. Most people love what they see even though it’s something, which if seen in real life, would disgust and repulse them.

Adam: At first I think most people think working with animal innards to be a little gross, but really there’s lots to offer aesthetically in the inside. Ribs, lungs and guts provide very interesting patterns and textures. Blood stains and feces add color. These are the parts of the animal that are not usually seen so they catch the viewer’s attention and cause reason for pause. If, for example, the animal is a road kill specimen, whose guts are spilling out—well that’s an interesting story that we can capture on paper.

Do you try to position the specimens in a certain way on the paper?

Adam and Ben: Absolutely. We think about position quite a bit. Mainly we want to capture natural poses, either making the animal seem alive or dead. Often if the animal has rigor mortis or could fall apart, due to rot, we are limited to how we can pose them. Sometimes animals come to us very disfigured, depending on the cause of death, and we’ve been surprised by the beautiful prints that can be obtained from them.

Can you take me through the process of making a print? What materials do you use, and what is your method?

Adam and Ben: We are always experimenting with different papers, fabric, inks, clays and paints as well as different application methods, but it really all boils down to applying a wet media to the animal and then applying it to paper or fabric. The trick is finding the right kinds of materials and transfer technique for each kind of specimen. The process for bones is very different than fleshed out animals; and birds are different than fish. Having two of us is often essential for large floppy animals where we want to apply the animal to the table-bound paper. Fish can be the most difficult; their outer skin is essentially slime, which repels some inks and creates smudgy prints on paper. You have to remove this outer slime layer before you print a fish. Salt seems to work well for this. We often do varying degrees of post-processing of the raw print with paint or pencils.

What do you add by hand to the actual print?

Ben: For each animal we’ll likely do half a dozen to a couple dozen prints searching for the perfect one. With all these replicates, we’ll play around with different techniques of post processing. The traditional Gyotaku method restricts touch-ups to accenting the eye of the fish. I think we’ve at minimum done this. But we’ve employed a lot of post-processing techniques, including pencil, watercolor, acrylic, clay, enamel and even extensive digital touch ups.

Adam: There is a balance that we are trying to achieve regarding preserving the rawness of the print and creating a highly refined piece. We like both and find ourselves wavering. Recently, we’ve started to assemble prints together digitally and sometimes alter colors and contrast for interesting effects.

What are the most challenging specimens to print?

Adam: I think small arthropods (animals with exoskeletons) are particularly difficult and time consuming. We’ve come up with the best method, to completely disassemble the animal and print it in pieces. The other trick with them is to apply the ink very thinly and evenly. Anything with depth is also difficult and sometime impossible since the way paper and fabric drapes across the animal can result in very distorted looking prints.

Ben: Small fish or insects. Fish because they are just so small, and the details like scales and fin rays don’t come out well. And, insects because they can be so inflexible, and their exoskeletons are, for the most part, pretty darn water repellent, restricting what kinds of paints we can use.

What animal would you like to print that you haven’t yet?

Ben: Generally, I’d love to print any animal that we haven’t already printed. That said, I have a gopher in my freezer that I’m not too excited about because it will likely turn out as a hairy blob. And once you’ve done one snake, another the same size is hard to distinguish. Large animals are, of course, charismatic and impressive, but I also really enjoy the challenge of trying to capture details on smaller animals. There are some animals that do, in theory, lend themselves to printing. For example, we have a porcupine in our freezer that I’m really excited about.

Adam: I get excited about anything new really. To date, we’ve been primarily interested in working with Texas fauna, but we are excited about other possibilities as well. I especially like animals with interesting textures juxtaposed. For example, I think the more-or-less naked head and legs of an ostrich with the feathery body would be interesting and very challenging. But, beyond specific animal species, we’re now experimenting with the process of rot, a commonality of all dead animals. One project involves placing a fresh animal on paper and spray painting it at various intervals with different colors as it rots and expands. The result is an image of the animal surrounded by concentric rings that document the extent of rot through time.

What do you hope viewers take away from seeing the prints?

Ben and Adam: We like to think there is something in the animal prints that captures both the spirit and the raw corporeal feel of the animal. It’s amazing to us that the art was created by using an animal as a brush so-to-speak, and that there’s even DNA left on the art itself. We hope people have a similar thought process and feeling about the work. We also hope that the project and print collection as a whole serves as a way people can better approach and appreciate the biodiversity around us.

Ben Labay will be showing works from the Inked Animal Project at his home in Austin on November 16-17 and 23-24, as part of the 12th annual East Austin Studio Tour (EAST), a free self-guided tour of the city’s creative community. Inked Animal works are represented by Art.Science.Gallery in Austin, Texas—one of the first galleries in the country to focus on science-related art.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)