The Complicated Calculus of Counting Emperor Penguins

Scientists journey to the icy bottom of the Earth to see if satellite imagery can determine how many Emperor penguins are left in the world

:focal(1100x1068:1101x1069)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/32/47/324725e8-25b7-4be4-bb10-25f7d3145bc5/istock-147290529.jpg)

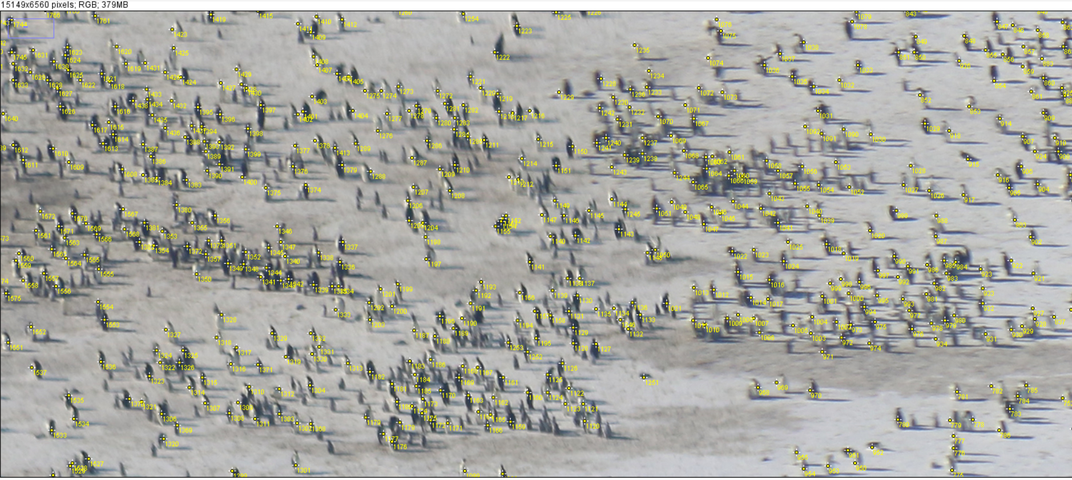

From above they resemble tiny black and white figurines, frozen in place and belonging to some past world. Emperor penguins are, in many ways, other-worldly, having evolved to survive the harshest winters on Earth. Through a 400-millimeter zoom lens positioned out a helicopter window, the mated pairs appear as antique porcelain salt shakers peppered with snow on a dusty shelf of ice.

Antarctica is not for the faint of heart. For a hundred years, explorers and biologists have been mesmerized by its brutality. It makes sense, then, that we would be captivated by the only species that attempts to breed through the continent’s unforgiving winters. We've followed the marches, triumphs and egg breakthroughs of the Cape Crozier Emperor penguin colony on the silver screen. For ten years our satellites have snapped photos of the 53 other known colonies, when cloudless days and orbits align. Now, an international effort is bundling up to see whether these images from space can tell us, for the first time, how many Emperor penguins are left in the world.

"Most of what we know about Emperor penguin populations comes from just a few well-studied colonies. We're actually not sure how most populations are doing," says Dave Iles, a postdoctoral researcher at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Massachusetts. "But satellite data will completely change that."

Iles is part of the team of scientists testing whether high-resolution images taken from satellites can be used to track which colonies are growing and which may be at risk of collapse. Following climate models that predict widespread declines in sea ice by the end of the century, anticipated Emperor penguin declines are so dramatic that some experts are seeking to list them under the Endangered Species Act. But to do this will require an international collaboration to hand count every last bird.

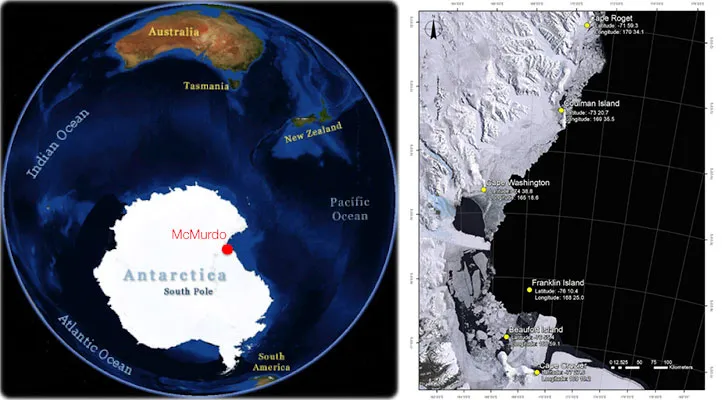

Assistant Professor of Marine Sciences Michelle LaRue is leading the charge at the McMurdo U.S. Antarctic Research Station. She recently relocated from the University of Minnesota to the University of Canterbury in New Zealand, in part to be closer to the Antarctic port. LaRue feels calm in the regal presence of Emperor penguins. She turned a job mapping Antarctic habitat data from a desk in Minnesota into a career monitoring Antarctica’s most charismatic beasts, including Weddell Seals and Adelie penguins—the Emperor's smaller, sillier cousins. On this trip to Antarctica, her seventh, LaRue assembled a team to help match images of Emperor penguin colonies taken from helicopters to those taken from much farther above by satellite. The expedition visited seven colonies along the Ross Sea near the McMurdo base and counted the closest colony five times to gauge how much penguin numbers fluctuate from day to day.

"For the first time we will be able to empirically say how many Emperor penguins there have been and how those populations have changed over ten years," LaRue says. "To this day, the work that has been done has all been modeling."

Back at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Massachusetts, the woman behind the models is Stef Jenouvrier, a French seabird ecologist who studies the response of animal populations to climate change. She and postdoctoral researcher Sara Labrousse, also from France, have teamed up with LaRue, Iles and Leonardo Salas, a quantitative ecologist with Point Blue Conservation Science, to combine a decade of data from satellite images with ecological models of how animal populations fluctuate over time. Their goal is to better understand how Emperor penguins are faring as the ice warms and changes in response to climate change.

Jenouvrier says she's never been a bird watcher but was lured into the project by the availability of data on these mysterious Antarctic Aves. Now Jenouvrier is hooked, and she's also hooked Labrousse, a 2012 Olympic competitor in synchronized swimming who flipped her underwater credentials into a PhD on elephant seals, large predators that hunt beneath the Antarctic ice.

Together with the rest of the international Antarctic Emperor penguin research team, they hope to map out how Emperor penguins move around on the ice to find food, warmth and mates—and to determine how many of these animals are left. In 2009, computer models estimated a population of 600,000 individuals. It’s time to see how they’re doing.

************

The first day in the air, the team counts 1,536 penguins from stitched-together photos they took of the Cape Crozier colony nestled into a sheltered crack in the ice. Iles and Labrousse shoot the photos out the helicopter windows while Salas takes notes, LaRue directs and the pilot, Jesse Clayton, circles high above so as not to disturb the colony’s behavior. On the next category two day—when high winds and low visibility ground all flights—the team orders pizza and compares their penguin counts from aerial photos and satellite imagery.

Iles has worked in iced-over edges of the Earth before. He spent eight summers studying how snow geese respond to climate change in Manitoba, Canada, while keeping watch through arctic fog for polar bears with a nasty habit of blending in with white rocks. This is his first trip to the southern polar region, and it's the first time his coffee has frozen while walking outside between two research buildings.

The scale of Antarctica is hard to put into words, Iles says. An active volcano behind the McMurdo station regularly spits balls of fire into the sky. A 13,000-foot mountain rises in a weather system that intimidates even seasoned Everest rescue pilots. And a 100-year-old seal carcass left by early explorers looks like it was cut open yesterday, its oily innards spilled onto the ice, perfectly preserved.

For all that Antarctica holds constant—its biting winds, its unmerciful cold, its promise of vast yet deadly adventure—the very platform on which it exists is ever-changing. Winter lasts from March to October. After the very last sunrise of summer, when most researchers have returned to their mainland bases in the spring of the Northern Hemisphere, temperatures in Antarctica drop and the surface of the ocean begins to freeze. First it spreads as a thin layer of grease ice. Then pancake ice forms as the greasy layers thicken. A stack of pancakes is either carried out to sea as drift ice or pushed into the mainland to form pack ice, which will become habitat for species like Leopard seals, Snow petrels and Adelie penguins when they return in later, brighter months. Emperor penguins rely on both pack ice and fast ice, or land-fast ice, which forms along the coastlines in shallow bathymetry. As global temperatures and oceans warm, all this habitat could be at risk of melting away. In Antarctica, though, nothing is quite that simple.

"So far, the sea ice changes have not been attributed, for sure, to climate change," Jenouvrier says. "Natural variation in the Antarctic is so huge that it's hard to determine the exact influence of climate change. It's not as clear as it is in the Arctic, where we know sea ice is melting. The weather patterns in Antarctica are more complex."

"You have a lot of different systems changing together," Labrousse adds.

************

Phil Trathan, a Conservation Biologist with the British Antarctic Survey, also tracks Emperor penguins using satellite imagery and has collaborated with LaRue and Jenouvrier in the past. He works on counting colonies near the British Research Station, some 2,000 miles away on the other side of the South Pole from McMurdo. Both groups are part of a broader network of "Emp researchers," as Trathan calls them. Last year, his crew did fly-overs to monitor the 15 Emperor colonies between 0- and 19-degrees West.

The colony nearest the British station, however, has disappeared. So far, Trathan's crew can’t explain what happened to their seabird neighbors. He'd like to return to Antarctica to search for the lost colony, but colonies in the Weddell Sea area are difficult to access. Penguins rely on huddling together for warmth, so dwindling colonies often give up their post and join another nearby group. But penguins can't be tracked with GPS collars, for ethical and practical reasons, and scientists have no way to know for sure what has become of a vanished colony.

The disappearance is one of the mysteries that a detailed satellite imagery map of Emperor penguins could help solve. When all the scientists in the Emp network put their counts together, they'll have data on how many individuals live at each of the 54 penguin colonies and how much they shift between colonies over time, mixing with other groups as they traverse their icy world.

"For a few penguins to move in a stepping-stone pattern around the continent actually helps the whole species," Trathan says. But such changes make the wellbeing of individual colonies hard to assess.

In addition to allowing groups to combine for greater huddle warmth, this colony-exchange behavior helps diversify penguin genetics, making the entire species more robust to new conditions. Jenouvrier is just starting to incorporate genetic information into her models of population dynamics. Confirming that satellite imagery can account for all the penguins in different locations across the continent will give her models the backbone to guide penguin policy decisions.

Trathan sits on the penguin specialist group of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) that oversees endangered species listings. It's a complicated process, and getting the science right is the first step, he says, followed by consideration of policy options and the benefits of listing a species as endangered. Trathan has witnessed decreases in the extent of fast ice where penguins breed in addition to the disappearance of whole colonies. But he's waiting for numbers from the rest of the Emp network before making up his mind about whether the species should be listed.

John Hocevar favors more immediate protections. As the director of Greenpeace's Protect the Oceans campaign since 2004, Hocevar doesn't think we can afford to wait for government regulations to protect marine ecosystems. With the Antarctic peninsula warming faster than almost any other region on Earth, he says the future of Emperor penguins demands action now.

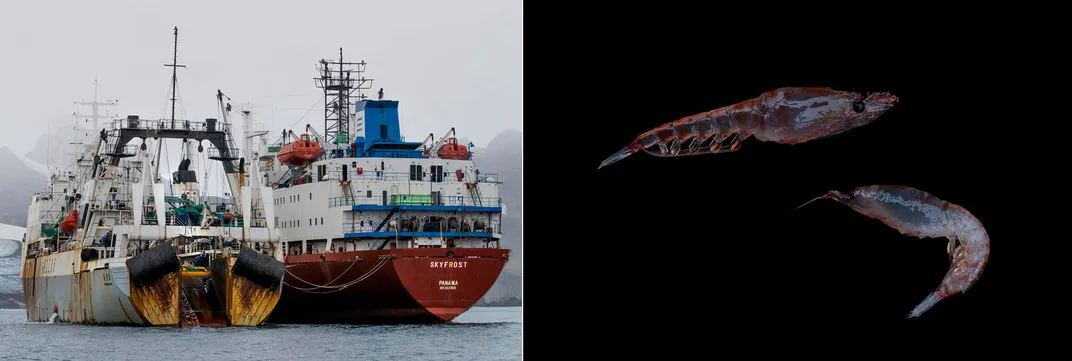

"The biggest concerns are climate change and fishing," Hocevar says. "We're starting to see declines in krill in key areas. At the same time, we have industrial facilities vacuuming up krill directly. Without krill nearby, penguins would be in real trouble. If you're a penguin, the longer you have to leave to find food, and leave your chick vulnerable to predators, the worse your chances of survival."

Hocevar has seen the krill situation firsthand. He was in Antarctica last year piloting a submarine on the icy seafloor to survey an area proposed for a new marine sanctuary. Penguins circled the team's boat while they got the submarine ready on deck. As Hocevar descended, he watched the birds hunt for krill and fish through the icy, clear water. Down in the darker waters below, his team found microplastics in every seafloor trawl they pulled up, which Hocevar thinks may be an understudied threat to penguins.

"Part of the solution for penguin conservation, and every other animal, is to get away from the idea that we can use something once and throw it away," Hocevar says. "There really is no 'away.'"

Hocevar's group uses satellite imagery to track pirate fishing, deforestation and oil spills. He's optimistic about what LaRue and Jenouvrier's work using satellite imagery will contribute to Emperor penguin conservation. Developing management plans that scientists have confidence in will require understanding basic questions of how many Emperor penguins remain and how their populations are growing and shrinking. In the past, the enormous practical challenges of traveling to monitor all 54 colonies, combined with the rapid rate of change in Antarctic conditions, made this a Mt. Erebus-sized task. Being able to model change via satellite offers new hope.

To tackle the computation, LaRue has enlisted Heather Lynch at New York's Stony Brook University. Lynch studies statistical applications for conservation biology riddles, such as survivorship in mammals and biodiversity patterns of dendritic networks. When the "Emp network" finishes hand-counting the penguins in all 54 colonies, Lynch will try to train a computer to replicate their results.

"The pie-in-the-sky goal there would be, at some point, to be able to feed an image into this program, and on the other side it would just tell us how many penguins there are," LaRue says. Without eyes in orbit, keeping such counts up to date would be near impossible.

***********

Even when future computers and satellites conspire to count penguins without our help, scientists will still need to journey to Antarctica to observe the anomalies an algorithm would miss. While circling the Cape Crozier Emperor penguin colony for the third time, Iles spotted a dark guano stain on the ice in the distance. Thinking it was a smaller outpost of breeding Emperor penguins they had missed on previous flights—guano stains are a helpful indicator of colonies from above—he asked the pilot to investigate. It turned out to be a group of 400 Adelie penguins, which are typically found living on rock piles and are not known to leave guano stains on the ice.

"I contacted the Adelie penguin experts immediately and asked them ‘What is this? Have you seen this before?’ LaRue says.

Adelie penguins living on ice instead of rock had been documented in the 1970s, but it's rare and had never before been seen in such numbers. When they reviewed the aerial photos, the team noticed little divets in the ice, evenly-spaced, suggesting nesting activity. This discovery could complicate Lynch's algorithms, since guano stains on ice had been assumed to indicate the presence of an Emperor colony. Now the possibility that such stains are from Adelie penguins will have to be factored in. But LaRue thinks the sighting says more about the changing ways of Adelie penguins, the transformations of Antarctica in general, and the ever-present need to return to the ice to find out more.

For now, the team has all the data they need, having successfully visited all seven target colonies and counted the Cape Crozier birds on five separate days. They'll use the information to account for daily fluctuations in models of Emperor penguin populations. With the ice adventure wrapped up, there's plenty of scientific tedium ahead.

"It was really nice to get out and see it,” Labrousse says, “because usually I just watch satellite images on my computer."

In the coming years, while the team continues to tally porcelain figurines in photos, while Lynch trains computers to count, while Trathan awaits the call to the IUCN seabird specialist meeting, and while the Antarctic ice melts, then refreezes to grease, then pancake, then pack ice, the Emperor penguins will continue to raise their chicks amid winter blizzards as they have always done. In the meantime, Hocevar suggests that efforts to replace coal with renewable energy, fishing channels with marine sanctuaries and single-use plastics with reusable containers may help increase the chances that we will find Emperor penguins nestled in the vast Cape Crozier ice crack for another hundred years.

All research photos of Emperor penguins taken under Antarctic Conservation Act permit #2019-006.