Antikythera Shipwreck Yields New Cache of Ancient Treasures

Scientists have recovered more than 50 artifacts from the site, including a bronze armrest that was possibly part of a throne

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/81/97/819735bc-87de-43fe-9986-92b3ac6f1c69/fig02_anti_150908_duw_bs-067a.jpg)

Over 2,000 years ago, the churning ocean below the cliffs of the Greek island Antikythera swallowed a massive ship loaded with a trove of luxuries—fine glassware, marble statues and, famously, a complex geared device thought to be the earliest computer.

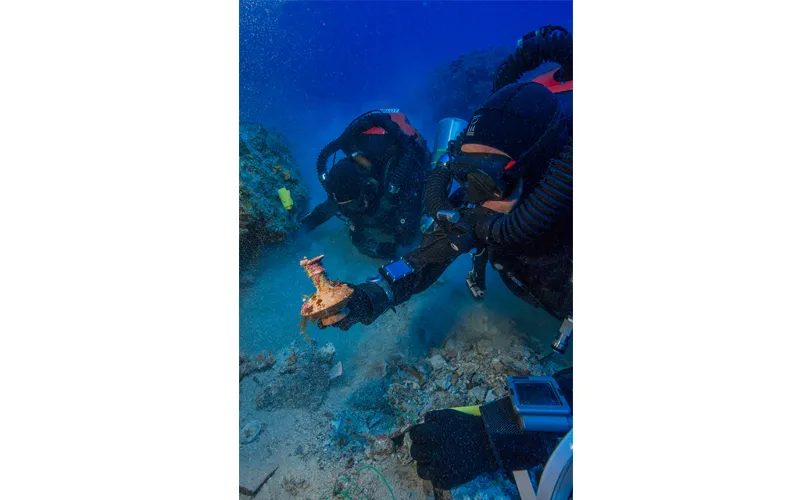

Discovered by Greek sponge divers in 1900, the shipwreck has since yielded some of the most impressive antiquities to date. And while severe weather has hampered recent dives, earlier this month a team of explorers recovered more than 50 stunning new items, including a bone or ivory flute, delicate glassware fragments, ceramics jugs, parts of the ship itself and a bronze armrest from what was possibly a throne.

“Every single dive on the wreck delivers something interesting; something beautiful,” marvels Brendan Foley, a marine archeologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute and co-director of the project. “It’s like a tractor-trailer truck wrecked on the way to Christie’s auction house for fine art—it’s just amazing.”

The wreck of the Antikythera ship hides beneath a few feet of sand and scattered shards of ceramic fragments at a depth of about 180 feet. Following an initial excavation funded by the Greek government, explorer Jacques Cousteau returned to the wreck in 1976 to mine the seemingly endless bounty, recovering hundreds of items.

But with even more modern advances in diving and scientific equipment, scientists believed the Antikythera wreckage had more secrets to reveal.

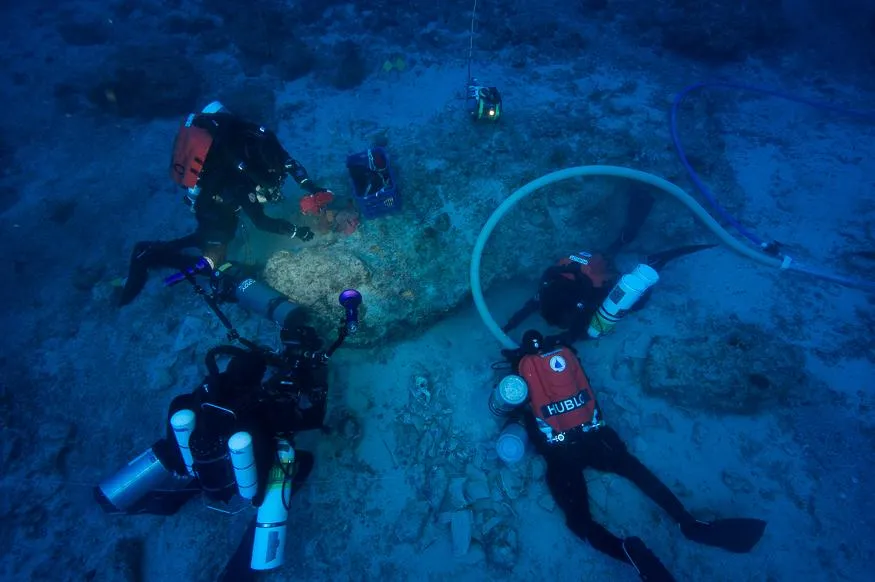

In 2014, an international team of archaeologists, divers, engineers, filmmakers and technicians embarked on the first excavation of this site in 40 years, using detailed and meticulous scientific techniques to not only find new treasures but also to try and reconstruct the ship's history.

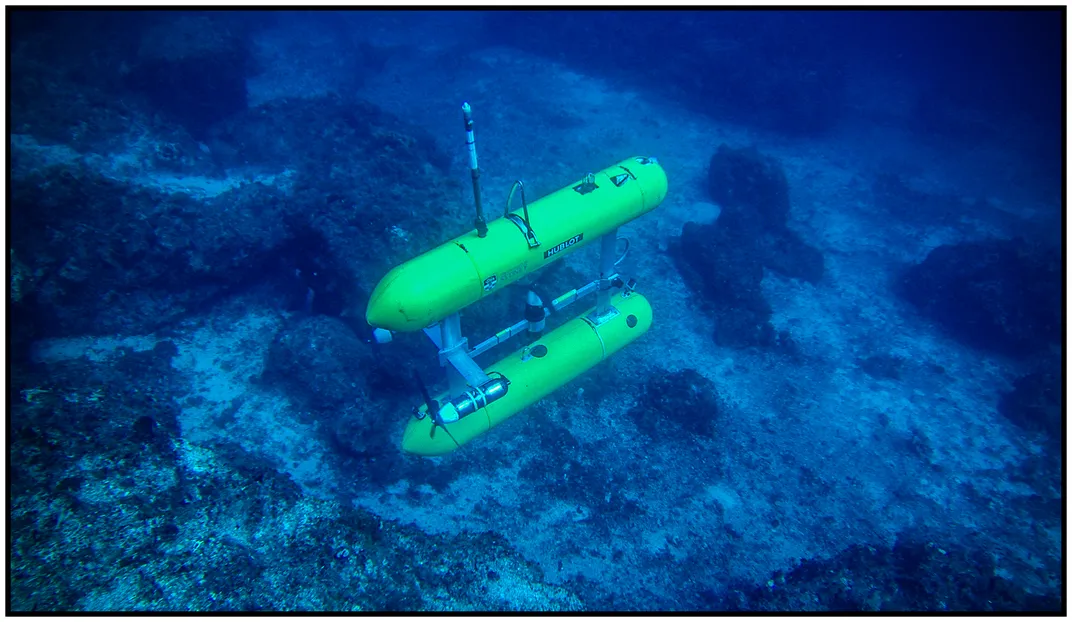

The team used autonomous robots to produce hyper-precise maps of the site in partnership with the University of Sydney Australia, says Foley. These maps—accurate down to about a tenth of an inch—were pivotal for both planning dives and mapping discoveries.

The team also carefully scanned the site with metal detectors, mapping out the extent of the wreckage and deciding where to excavate. Using waterproofed iPads, the divers could mark each new artifact on the map in real time.

For the latest round of dives, a ten-person team logged over 40 hours underwater, surfacing with the fresh haul. Analyzing the artifacts should provide the team with a wealth of information, says Foley.

The Antikythera shipwreck is spread across two different sites separated by about the length of a football field, he says. Analytic tools, like comparing the stamps on amphora handles from each site, will help scientists determine whether the wreck represents one or two ships.

If it was two ships, “that opens up a whole series of questions,” says Foley. “Were they sailing together? Did one try to help the other?”

Still, the large size of objects recovered at the primary wreckage site suggests that at least one ship was massive, akin to an ancient grain ship. One such item recently recovered as part of the latest haul was a lead salvage ring about 15.7 inches wide, used to straighten tangled anchor lines.

Scientists hope to learn more about the origin of the ship—or ships—by analyzing the isotopic composition of lead artifacts similar to this ring, which will yield information about where the vessel itself was made.

For the ceramic artifacts, the team plans to look closely at any residues preserved inside the container walls. “Not only are [the ceramics] beautiful in their own right, but we can extract DNA from them,” says Foley. That could give information about ancient medicines, cosmetics and perfumes.

The team currently has plans to head back out to the site in May, but the future of the project is open-ended. With so much information to glean from the current set of artifacts, Foley says that they could let the site sit for another generation. With the rapid advance of technology, future expeditions may have even better techniques and be able to discover even more about the wreckage.

“What will be available a generation from now, we can’t even guess,” he says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)