Art as Therapy: How to Age Creatively

A new exhibition at the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., showcases the work of elderly artists with memory loss and other chronic conditions

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Collage-Art-Therapy-631.jpg)

A few minutes late, I tiptoe into an alcove of the Phillips Collection, in Washington, D.C., where Brooke Rosenblatt is leading a discussion with ten museum visitors about Ernest Lawson’s oil painting Approaching Storm.

“Where do you think this scene takes place?” asks Rosenblatt. “Have you ever been to a place that looks like this?” She calls on audience members, who are all seated in folding chairs. The landscape of rolling hills and a stream lined with cattails seems to remind each person of a different place—Scotland, North Carolina, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, France, Switzerland. One gentleman in the front row is convinced it is upstate New York. “He obviously liked it,” he says of the artist’s relationship to the place. “It was lovingly painted.”

“Let’s step inside the picture,” says Rosenblatt. “What do you hear, smell, touch and taste?”

A man, sitting just in front of me, says he hears fish splashing in the brook. A woman in attendance hears distant thunder. And, another participant says she feels a precipitous temperature drop.

For about a year, the Phillips Collection and Iona’s Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Wellness and Arts Center, also in the nation’s capital, have partnered to offer an arts program for older adults with memory loss, Parkinson’s disease, the lingering effects of stroke and other chronic conditions. Rosenblatt, an education specialist at the Phillips, meets with participants, sometimes their family and caregivers as well, on a monthly basis; one month the group will visit the museum, and the next month Rosenblatt will bring reproductions of artworks to Iona, so that others who are less mobile can join in the conversation.

In the morning, the group discusses two to three paintings. Rosenblatt poses questions that might help individuals connect to the works on a personal level. A particular painting, for instance, may jog an old memory. Then, in the afternoon, there is an art therapy component. Jackie McGeehan, an art therapist at Iona’s Wellness and Arts Center, brings the participants together in her studio to do some art making of their own.

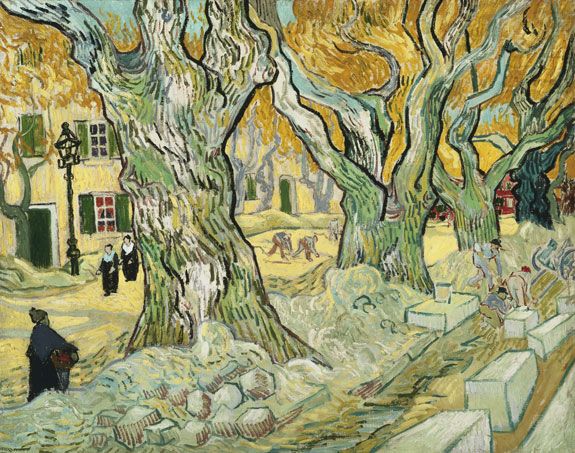

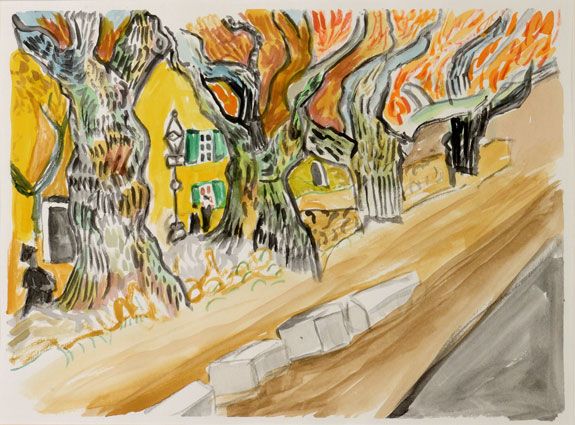

Throughout November, National Arts and Health Month, the Phillips Collection is displaying some of this art, created at Iona, in an exhibition called “Creative Aging.” The artworks are grouped together by monthly session and shown alongside a panel featuring the famous piece from the Phillips Collection that inspired them and a description of the themes discussed with museum educators and explored more fully in art therapy.

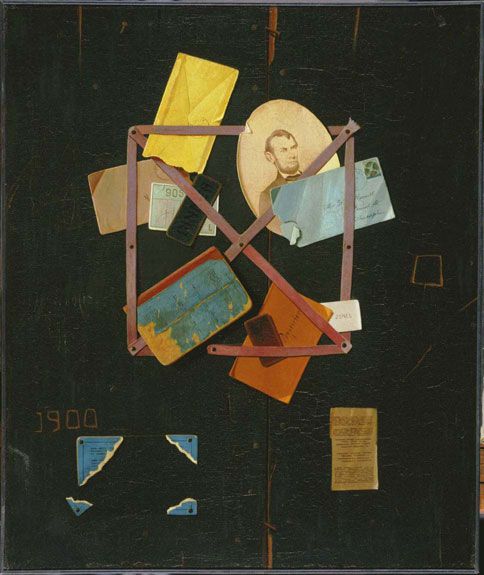

On the day I observe, Rosenblatt and other museum educators move from Lawson’s Approaching Storm to the next gallery, where John Frederick Peto’s painting Old Time Card Rack hangs. The still life, of sorts, shows letters, envelopes, tickets and a portrait of Abraham Lincoln tucked into a card rack, much like a bulletin board. Those attending discern that the objects must have held some meaning for the owner of the rack.

Based on the direction that the conversation takes, McGeehan chooses an art project. “Most of it comes down to my understanding of each of these people and what I think will be most beneficial emotionally. What is going to allow them to reach a little deeper?” she says, in a phone call a few days later. “A theme that I felt would be a good component to focus on was the idea of collecting and holding onto material goods or objects that remind us of moments in our lives.” In the art therapy studio, members of the program created “time stamps,” or art pieces that they can later look back on to remember this moment. Some people chose to respond to music, she said. Others created art or wrote letters to themselves.

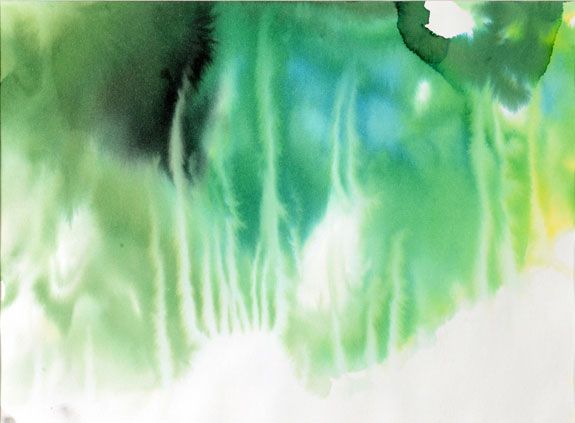

Visitors to the exhibition will see how Pablo Picasso’s The Blue Room and Raoul Dufy’s Chateau and Horses inspired the program’s artists to convey mood through color, and Morris Louis’ Seal encouraged them to explore the themes of movement and direction. After studying George Luks’ Otis Skinner as Colonel Philippe Bridau, they created self portraits in the art therapy studio. On another occasion, participants examined John Sloan’s Clown Making Up, talked about “masking” oneself and then sculpted plaster masks.

“In recent years, a wealth of scientific research has shown the powerful effects that interaction with the arts has on health, healing and rehabilitation,” reports the Phillips Collection, in a press release. “For individuals with Alzheimer’s and related dementia in particular, studies point to the ways art can ease the devastating symptoms and lessen the anxiety, agitation and apathy associated with the disease.”

McGeehan has also seen firsthand how art can help the aging population communicate their emotions in a non-verbal way. “Art is a very safe, very contained avenue for them to express themselves,” she says. “People that have suffered a stroke may have an expressive aphasia where they are unable to communicate clearly or have trouble finding or saying words, so it has given them an additional tool to help them be heard and understood by other people.”

In her experience, McGeehan finds that art therapy helps people who are declining physically and cognitively and becoming more dependent on other people. “They are given a material that they can mold, shape and really transform from nothing to something beautiful,” she says. “That sense of control and mastery over the process for many people is very valuable.”

Rosenblatt wraps up her discussion of Lawson’s Approaching Storm with an interesting question. “If you painted this, what would you call it?” she asks. Without hesitation, one man says, “House in Sunlight.” Others agree. Although clouds are rolling into the scene, there appears to be a bright patch surrounding a single white house, and they’ve fixed their gazes on it.

If that isn’t a sign that art therapy helps with positive thinking, I’m not sure what is.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)