Attempting to Fry an Egg on the Sidewalk Has Been a Summer Pastime for Over 100 Years

The Fourth of July is also National Fry an Egg on the Sidewalk Day, and no amount of scientific logic can crack this tradition

:focal(791x667:792x668)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/17/4e/174e6645-c818-49f6-8274-18988a94fd8c/istock-165065718.jpg)

Every Fourth of July, Americans release fireworks across the night sky—and, to a lesser extent, eggs across the nation’s sidewalks. National Fry an Egg on the Sidewalk Day, which happens to correspond with Independence Day, honors the strange tradition of putting summer’s heat to the test with nothing more than an egg and a slab of cement. A town in Arizona, for example, holds an annual July 4 contest to fry an egg outside without electricity or fire, but the notion of using the hot pavement for cookery has old—and rather unscientific—roots.

One of the earliest references to frying an egg on the sidewalk contained in the Library of Congress dates back to an 1899 issue of the Atlanta Constitution. In a column titled “How to Keep Cool,” Dr. Francis Henry Wade advises his readers: “With the thermometer cavorting away up among the nineties, with the bricks of the sidewalks hot enough to fry eggs, with ‘heat prostrations’ and sun strokes ‘filling bodies with anguish and bosoms with fear,’ as the poet puts it, the question 'How to keep cool?' becomes an all-absorbing one of the hour in the mind of every one, no matter what his vocation or walk of life.”

Some of Wade’s questionable medical advice—“Do not think about who is to be the next president or any other exciting subject”—wouldn’t hold much water today, but the concept of frying an egg on the sidewalk has stuck in the public consciousness. The only problem is that using concrete as a cooking surface, even in the highest of summer temperatures, is likely an impossible task.

With the help of a frying pan or other metal surface, however, culinary enthusiasts have long been attempting to make sun-cooked eggs. An October 1933 article in the Los Angeles Times helped further popularize the pastime in a report about record-breaking temperatures, between 102 and 112 degrees Fahrenheit, in the neighborhood of Van Nuys. “Sidewalks were so torrid the heat could be felt through shoe soles,” it says. “Nobody tried to fry eggs in the sun in the street, but discussions on every corner was to the effect that it could be done, if the eggs and the frying pan had been handy.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e4/68/e4687f60-fde4-42d1-bc76-adc3957351df/gettyimages-515142748.jpg)

Despite the popularity of the idea, the science of actually trying to fry an egg on the sidewalk—even with a pan—is a bit more complicated. The innards of an egg can be separated into two main parts, the yolk and the albumen. Both parts are made up of water and strings of negatively-charged proteins folded into clumps with the help of weak chemical bonds, like microscopic, crumpled-up paper chains. These proteins repel one-another, causing the watery whites to spread, while the yolk is held together by fats which counteract some of the protein charges.

When you cook an egg, the heat transfers energy to the molecules, causing the proteins to unravel. After a few minutes, the strings of proteins weave and bind together, and most of the water evaporates. The yolks and the whites are made of different proteins, so this process occurs at varying temperatures for different parts of the egg. Culinary experts fiercely debate the perfect temperature to cook an egg, but in general, the yolk proteins begin to condense near 150 degrees Fahrenheit, while the albumen proteins ovotransferrin and ovalbumin thicken near 142 and 184 degrees, respectively.

Chef Wylie Dufresne of Du’s Donuts & Coffee, a noted egg enthusiast, says the perfect egg comes down to personal taste. “I don’t think anyone should tell you that this is the way to cook an egg, because that’s not right.” For his own eggs, Dufresne says he prefers to cook them on medium-low heat near 145 or 150 degrees Fahrenheit for four to five minutes, with butter. “When I fry an egg, I like to cook it in a lower temperature pan, because I think a softly set egg white is magical,” he says, “but I understand that some people find that off-putting.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4b/fa/4bfa317b-e623-49df-bddb-00cee2f2109c/istock-475307062.jpg)

This process is straightforward enough with the convenience of a stove, but using concrete severely limits a cook’s ability to apply the right amount of heat. Instead of getting thermal energy from electricity or a direct flame, pavement relies on the absorption of light from the sun. Once absorbed, photons transfer their energy to the molecules in the pavement, causing them to vibrate, and enough vibration eventually conducts heat.

But not all roads are created equal—at least not for cooking eggs. Lighter materials like cement reflect most visible light, so few photons are absorbed. Darker pavements like asphalt, on the other hand, absorb most visible light, allowing the surface to get hotter. “Concrete isn't great, asphalt is probably better and less porous,” Dufresne says. “In order for this to work you want something that approximates a pan. It’s got to be smoother and tighter, and also going to be hotter and hold its heat better.”

But even with the darkest pathways, it’s hotly contested whether frying an egg without the help of a pan is possible. In his book, What Einstein told his cook: kitchen science explained, Robert Wolke found that a sidewalk will likely only get up to 145 degrees Fahrenheit—below the cooking temperature of most egg proteins. Concrete is also a poor conductor of heat in comparison to metal, and it cools slightly when the egg is cracked on the surface.

“If you’ve got a road that’s at 150 or 155 degrees and you crack an egg onto it, it’s going to lower the temperature, and that temperature’s not going to heat back up anytime soon,” Dufresne says. “If you put a couple eggs on a pan, the temperature drops immediately, but recovery is also very quick because you’re on a burner. There’s no recovery on the sidewalk or the road.”

The hottest ambient temperature recorded on Earth’s surface was only 134 degrees Fahrenheit, so it’s doubtful whether a sidewalk will ever be a successful skillet. "I would feel uncomfortable saying to you that it’s flat-out impossible, but I do feel comfortable saying it sounds pretty tough to do,” Dufresne says.

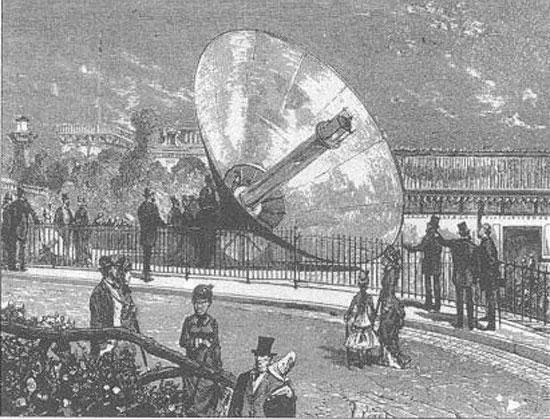

Egg enthusiasts with an engineering bent might try to enhance their cooking power by building off the pavement. A glass or plastic enclosure prevents reflected heat from escaping, like a car left in a parking lot. To get true frying power though, adding reflective materials to focus the sun’s rays is often the most effective technique. For instance, parabolic solar cookers use curved reflectors to focus light at the center of a pot or pan, and these sun-powered stoves can achieve temperatures above 400 degrees Fahrenheit.

Such inventive egg-cooking techniques are on display at the now-famous annual Oatman Sidewalk Egg Fry Contest in Oatman, Arizona, where contestants compete every Fourth of July to fry an egg using solar power in under 15 minutes. Creative participants come wielding a range of homemade contraptions, including mirrors, aluminum foil and magnifying glasses. In the end, local prestige and bragging rights are given to the chef with the most fried-looking egg—although some over-achievers also make bacon or home fries.

Other attempts to cook eggs outside in the heat have had varying levels of success. In Australia in 2015, temperatures near 111 degrees Fahrenheit set off a trend of YouTubers trying to sidewalk-prep their eggs, although the only successful efforts used iron skillets. Two years earlier, a similar YouTube video posted by an anonymous employee in Death Valley National Park sparked a frenzy of visitors braving the 120-degree heat to crack eggs straight onto the rocks, without much luck.

Despite his doubts, Dufresne says he’d have a plan if he were going to try an authentic sidewalk-frying experiment. “If you told me we were going to embark on this journey, here’s what I would do—I would look for a real smooth, freshly rolled asphalt. I would look for a temperature as hot as possible, certainly an absolute minimum of 150 or 160 degrees because of the temperature drop, and I’d leave the eggs in the car while we drove there so they can temper and get nice and warm.”

But don’t expect it to end in a taste test. “We’re not worried about food safety because we’re probably not going to eat it,” he says. “I mean, we’re going to crack them onto the road, so I don’t think food safety is a paramount concern right now.”

While science continues to question whether a true egg-on-a-sidewalk dish will ever be achieved, diehard experimentalists show no signs of getting off the beaten path.