Bean Leaves Don’t Let the Bedbugs Bite by Using Tiny, Impaling Spikes

Researchers hope to design a new bedbug eradication method based upon a folk remedy of trapping the bloodsuckers as they creep

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Surprising-Science-Bean-Bug-631.jpg)

For thousands of years, humans have shared their beds with blood-sucking parasites. The ancient Greeks complained of bedbugs, as did the Romans. When the lights go off for those suffering from this parasitic infestation today, from under the mattress or behind the bedboard creeps up to 150,000 of the rice grain-sized insects (though average infestations are around 100 insects). While bedbugs are one of the few parasites that live closely with humans yet do not transmit a serious disease, they do cause nasty red rashes in some of their victims, not to mention the psychological terror of knowing that your body becomes a buffet for crawling bloodsuckers after dark.

By the 1940s this age-old parasite was mostly eradicated from homes and hotels in the developing world. But around 1995, the bedbug tides again turned. Infestations began flaring up with a vengeance. Pest managers and scientists aren’t sure what happened, exactly, but it may have been a combination of people traveling more and thus increasing their chances of encountering bedbugs in run down motels or infested apartments; of bedbugs bolstering their resistance to common pesticides; and of people simply letting their guard down against the now unfamiliar parasites.

Large cities such as New York have particularly suffered from this resurgence. Since 2000, the New York Times has run dozens of articles documenting the ongoing plague of bedbugs, with headlines such as Even Health Dept. Isn’t Safe from Bedbugs and Bringing Your Own Plastic Seat Cover to the Movies.

As many hapless New Yorkers have found, detecting stealthy bedbugs is only the first step of what usually turns into a long, desperate eradication battle. Most people have to combine both pesticides and non-chemical methods for purging their apartments. In addition to dousing the apartment and its contents in pesticides, this includes throwing away all furniture the bugs are living on (streetside mattresses in NYC with a “BEDBUGS!” warning scrawled across them are not an out-of-the-ordinary sight), physically removing the bodies of poisoned bugs, subjecting the home to extreme heat or cold, or even hiring a bedbug sniffing dog. Sometimes, after so many sleepless nights and days spent meticulously combing the cracks between the mattress and sheets or searching behind couch cushions, residents simply throw up their hands, move out and start their lives over.

Recognizing this ongoing problem, researchers are constantly trying to come up with new methods for quickly and efficiently killing the pests. The latest technique, described today in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface, takes a hint from mother nature and history. For years, people in Eastern Europe’s Balkan region have known that kidney bean leaves trap bedbugs, sort of like a natural fly paper. In the past, those suffering from infestations would scatter the leaves on the floor surrounding their bed, then collect the bedbug-laden greenery in the morning and destroy it. In 1943, a group of researchers studied this phenomenon and attributed it to microscopic plant hairs called trichomes that grow on the leaves’ surface to entangling bed bug legs. They wrote up their findings in “The action of bean leaves against the bedbug,” but World War II distracted from the paper and they wound up receiving little attention for their work.

Rediscovering this forgotten research gem, scientists from the University of California, Irvine, and the University of Kentucky set out to more precisely document how the beans create this natural bedbug trap and, potentially, how it could be used to improve bedbug purging efforts. “We were motivated to identify the essential features of the capture mechanics of bean leaves to guide the design and fabrication of biomimetic surfaces for bed bug trapping,” they write in their paper.

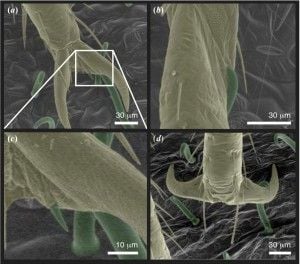

They used a scanning electron microscope and video to visualize how the trichomes on the leaves stop the bedbugs in their ravenous tracks. Rather than a Velcro-like entanglement as the 1943 authors had suggested, it seems that the leaves stick into the insects’ feet like giant thorns, physically impaling the pests.

Knowing this, the researchers wondered if they could improve upon the method as a way to treat bedbug infestations, because leaves themselves dry out and can’t be scaled up to larger sizes. “This physical entrapment is a source of inspiration in the development of new and sustainable methods to control the burgeoning numbers of bed bugs,” they write.

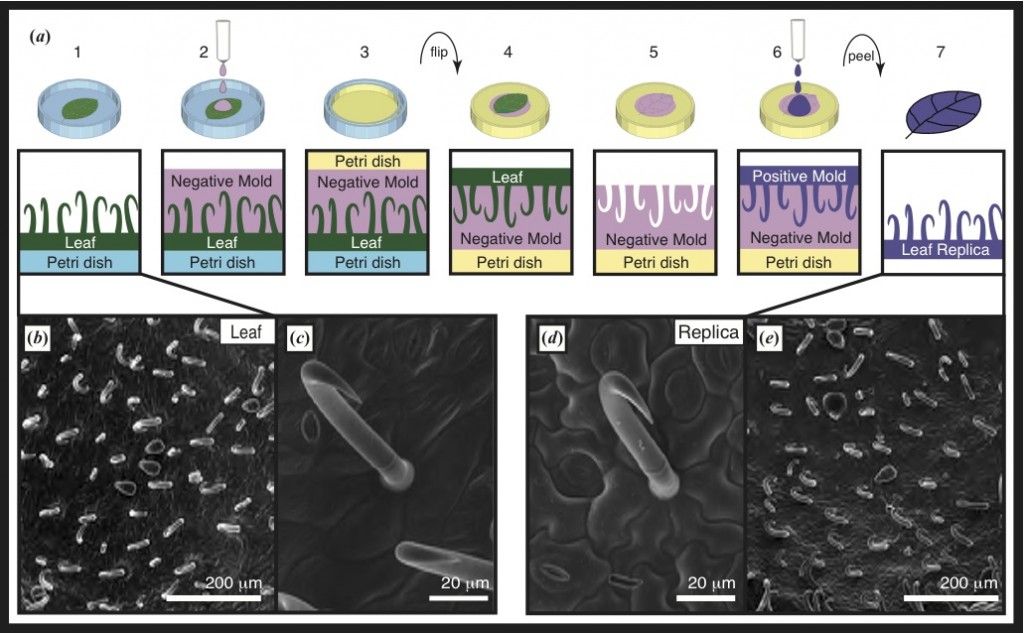

They used fresh bean leaves as a template for micro-fabricating produced surfaces that precisely mimicked the leaves. To do this, they created a negative molding of the leaves, then poured in polymers sharing a similar material composition of the living plant’s cell walls.

The team then allowed bedbugs to walk across their synthetic leaves to test their effectiveness compared to the real deal. The fabricated leaves did snag the bugs, but they didn’t hinder the insects’ movements quite as effectively as the living plants. But the researchers are not deterred by these initial results. They plan to continue working on the problem and improving their product by more precisely incorporating the mechanical properties of the living trichomes. The optimistically conclude:

With bed bug populations skyrocketing throughout the world, and resistance to pesticides widespread, bioinspired microfabrication techniques have the potential to harness the bed bug-entrapping power of natural leaf surfaces using purely physical means.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)