Beatboxing, as Seen Through Scientific Images

To see how certain sound effects are humanly possible, a team of University of Southern California researchers took MRI scans of a beatboxer in action

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130130114015DougEFresh-web.jpg)

It is always interesting to watch a beatboxer perform. The artist, in the thrust of performing, can reach a compulsive fit as he musters up the rhythmic sounds of percussion instruments a cappella-style.

But what does beatboxing looking like from the inside?

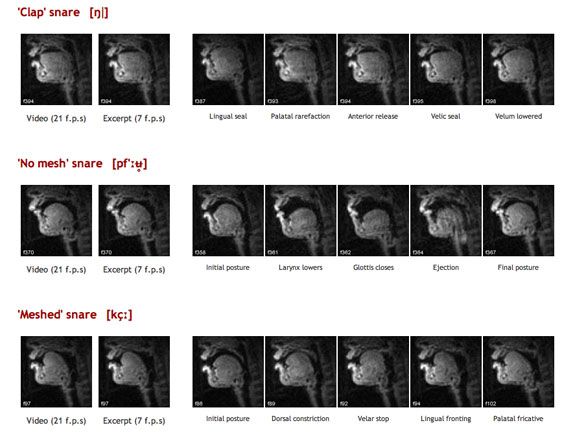

That is the question that University of Southern California researchers Michael Proctor, Shrikanth Narayanan and Krishna Nayak asked in a study (PDF), slated to be published in the February issue of the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. For the first time, they used real-time Magnetic Resonance Imaging to examine the so-called “paralinguistic mechanisms” that happen in a beatboxer’s vocal tract.

For the purposes of the experiment, a 27-year-old male hip hop artist from Los Angeles demonstrated his full repertoire of beatboxing effects—sounds imitating kick drums, rim shots, hi-hats and cymbals—while lying on his back in an MRI scanner. The researchers made a total of 40 recordings, each from 20 to 40 seconds in duration and capturing single sounds, free-style sequences of sounds, rapped or sung lyrics and spoken word. They paired the audio with video stringing together the MRI scans to analyze the airflow and the movements, from the upper trachea to the man’s lips, that happened with each utterance.

“We were astonished by the complex elegance of the vocal movements and the sounds being created in beatboxing, which in itself is an amazing artistic display,” Narayanan told Inside Science News Service, the first to report on the study. “This incredible vocal instrument and its many capabilities continue to amaze us, from the intricate choreography of the ‘dance of the tongue’ to the complex aerodynamics that work together to create a rich tapestry of sounds that encode not only meaning but also a wide range of emotions.”

It was a humbling experience, added Narayanan, to realize how much we have yet to learn about speech anatomy and the physical capabilities of humans when it comes to vocalization.

One of the larger goals of the study was to determine the extent to which beatbox artists use sounds already found in human languages. The researchers used the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) to describe the sound effects produced by their subject and then compared those effects to a comprehensive library of sounds, encompassing all human languages.

“We were very surprised to discover how closely the vocal percussion sounds resembled sounds attested in languages unknown to the beatboxer,” Michael Proctor told Wired. The hip hop artist who participated in the study spoke American English and Panamanian Spanish, and yet he unknowingly produced sounds common to other languages. The study states:

…he was able to produce a wide range of non-native consonantal sound effects, including clicks and ejectives. The effects /ŋ||/–/ŋ!/–/ŋ|/ used to emulate the sounds of specific types of snare drums and rim shots appear to be very similar to consonants attested in many African languages, including Xhosa (Bantu language family, spoken in Eastern Cape, South Africa), Khoekhoe (Khoe, Botswana) and !Xóõ (Tuu, Namibia). The ejectives /p’/ and /pf’/ used to emulate kick and snare drums shares the same major phonetic properties as the glottalic egressives used in languages as diverse as Nuxáalk (Salishan, British Columbia), Chechen (Caucasian, Chechnya), and Hausa (Chadic, Nigeria).

Going forward, the researchers would like to study a larger sample of beatboxers. They’d also like to get to the bottom of something that has been boggling audiences for decades: How do some beatboxers simultaneously layer certain instrumental sounds with hums and spoken words?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)