Before the Jetsons, Arthur Radebaugh Illustrated the Future

In the 1950s and ‘60s, the newspaper cartoonist dreamed up a madcap American utopia, filled with flying cars and fantastical skyscrapers

In the late 1950s and early ’60s, no one shaped Americans’ expectations of the future quite like Arthur Radebaugh, the illustrator of the popular newspaper comic “Closer Than We Think” as well as countless advertisements and magazine covers.

“We all dream of a better, brighter, more exciting future where the wonders of technology are there to serve and entertain us,” and Radebaugh “made that fabulous world of tomorrow seem practically at our fingertips,” says Todd Kimmell, the director of the Lost Highways Archives and Research Library, which is dedicated to American road culture.

An exhibition that Kimmell co-curated in 2003 traveled from Philadelphia to France to Detroit and won Radebaugh a new generation of fans. “The Da Vinci of retro-futurism,” a Wired magazine blog called him.

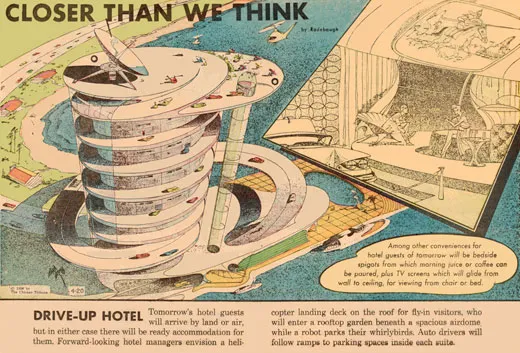

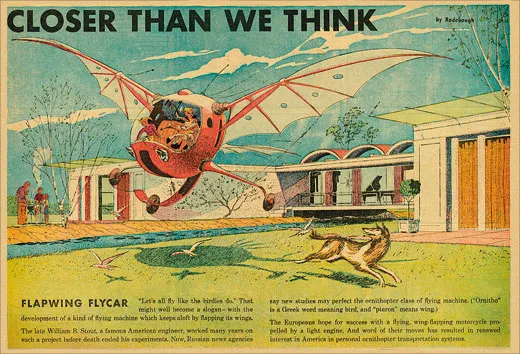

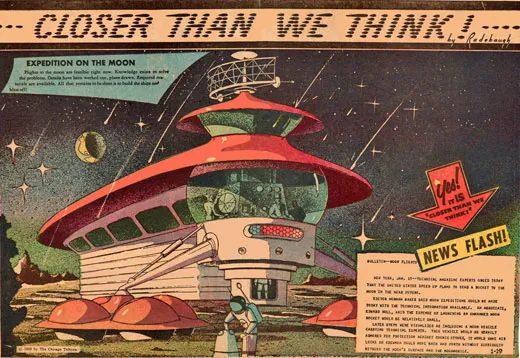

Radebaugh was a commercial illustrator in Detroit when he began experimenting with imagery—fantastical skyscrapers and futuristic, streamlined cars—that he later described as “halfway between science fiction and designs for modern living.” Radebaugh’s career took a downward turn in the mid-1950s, as photography began to usurp illustrations in the advertising world. But he found a new outlet for his visions when he began illustrating a syndicated Sunday comic strip, “Closer Than We Think,” which debuted on January 12, 1958—just months after the Soviet Union launched Sputnik—with a portrayal of a “Satellite Space Station.”

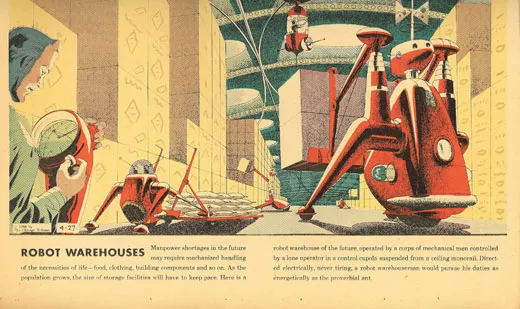

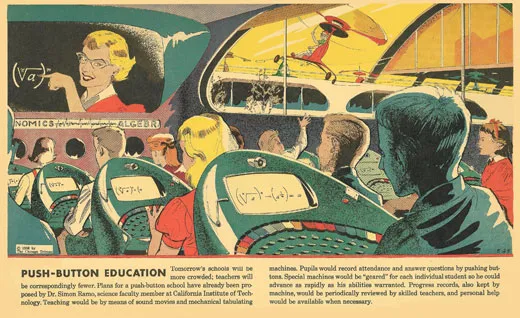

Week after week, he enthralled readers with depictions of daily life enhanced by futuristic technology: mailmen making their daily rounds via jet packs, schoolrooms with push-button desks, tireless robots working in warehouses. “Closer Than We Think” ran for five years in newspapers across the United States and Canada, reaching about 19 million readers at its peak.

When Radebaugh died in a veterans hospital in 1974, his work had been largely forgotten—eclipsed by the techno-utopian spectacles of “The Jetsons” and Walt Disney’s Tomorrowland. But more than two decades later, Kimmell acquired photos of Radebaugh’s portfolio that had been stashed in the collection of a retiring photographer and began reviving interest in his work.

“The future caught up with him several times,” says Kimmell, “yet he managed to change and readdress it in a different way.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)