Berried Treasure

Why is horticulturalist Harry Jan Swartz so determined to grow an exotic strawberry beloved by Jane Austen?

There's something curious going on at the pick-your-own strawberry farm amid the bland expanse of tract homes and strip malls southwest of Miami. In row after row on the ten-acre property, the plants appear uniform, but in a far corner set off by a line of habanero chili vines, each strawberry plant has a slightly different color and growth pattern. This is a test plot where a stubborn University of Maryland horticulturist named Harry Jan Swartz is attempting to breed a strawberry unlike any tasted in the United States for more than a century. He's searching for what may be the most elusive prize in the highly competitive, secretive, $1.4 billion-a-year strawberry industry—marketable varieties with the flavor of Fragaria moschata, the musk strawberry, the most aromatic strawberry of all.

Native to the forests of central Europe, the musk strawberry is larger than fraises des bois, the tiny, fragrant, wild alpine strawberries beloved by backyard gardeners, and smaller than the common strawberry, the supermarket-friendly but often dull-tasting hybrid that dominates sales worldwide. The musk strawberry has mottled brownish red or rose-violet skin, and tender white flesh. Its hallmark is its peculiar floral, spicy aroma, different from and far more complex than the modern strawberry's, with hints of honey, musk and wine; a recent analysis by German flavor chemists detected notes of melon, raspberry, animal and cheese. Adored by some people, detested by others, the aroma is so powerful that a few ripe berries can perfume a room.

From the 16th to the mid-19th centuries, the musk strawberry—known as moschuserdbeere in Germany, hautbois in France and hautboy in England—was widely cultivated in Europe. In Jane Austen's Emma, guests at a garden party rave about it: "hautboy infinitely superior—no comparison—the others hardly eatable." But because growers in those days did not always understand the species' unusual pollination requirements, musk cultivations typically had such scanty yields they seemed virtually sterile. Thomas A. Knight, an eminent horticulturist and pioneering strawberry breeder, wrote in 1806: "If nature, in any instance, permits the existence of vegetable mules—but this I am not inclined to believe—these plants seem to be beings of that kind." Also, the berries are very soft, so they don't keep or travel well. By the early 20th century, musk varieties had mostly disappeared from commercial cultivation, replaced by firmer, higher yielding, self-pollinating modern strawberries.

But the legend of the musk strawberry persisted among a few scientists and fruit connoisseurs. Franklin D. Roosevelt, who became enamored of its musky flavor as a boy traveling in Germany, later asked his secretary of agriculture and vice president, Henry A. Wallace, to encourage government strawberry breeders to experiment with musk varieties at the Agriculture Department's breeding collection in Beltsville, Maryland. It was there, in the early 1980s, that the musk aroma captivated a young professor at the University of Maryland, in nearby College Park.

After years at the forefront of berry science, Swartz in 1998 launched an audacious private program to overcome the biological barriers that had thwarted breeders for centuries. "If I can grow a huge, firm fruit that's got the flavor of moschata," Swartz told me a few years ago, "then I can die in peace."

On this unusually chilly January dawn outside Miami, we're checking up on his dream at his test plot next to a weed-choked canal. Swartz, 55, is wearing a black polo shirt and chinos. He is shivering. He bends over and examines a plant, ruffling the leaves to expose the berries. He picks one, bites into it. "Ugh." He makes notes on a clipboard. He tries another, and wrinkles his nose. "That’s what I call a sick moschata." The fruit has some of the elements of musk flavor, he explains, but with other flavors missing or added, or out of balance, the overall effect is nastily deranged, like a symphony reduced to cacophony.

Before the day is done Swartz will have scoured the test patch to sample fruits from all 3,000 plants, which are seedlings grown from crosses made in his Maryland greenhouse. They belong to his third generation of crosses, all ultimately derived from wild strawberry hybrids devised by Canadian researchers.

Swartz keeps tasting, working his way down the seven rows of plants sticking out of the white-plastic covered ground. "Floor cleaner," he says of one. "Diesel." "Sweat socks." He is not discouraged—yet. For many years, until his knees gave out, Swartz was a marathon runner, and he's in this project for the long haul, working test fields from Miami to Montreal in his unlikely quest to discover a few perfect berries.

“You’ve got to kiss a lot of frogs in order to find a princess,” he says.

The modern cultivated strawberry is a relative newcomer, the result of chance crosses between two New World species, the Virginian and the Chilean, in European gardens starting about 1750. This "pineapple" strawberry, called F. x ananassa, inherited hardiness, sharp flavor and redness from the Virginian, and firmness and large fruit size from the Chilean. In the 19th century, the heyday of fruit connoisseurship, the best varieties of this new hybrid species (according to contemporary accounts) offered extraordinary richness and diversity of flavor, with examples evoking raspberry, apricot, cherry and currant.

Alas, no other fruit has been so radically transformed by industrial agriculture. Breeders over the decades have selected varieties for large size, high production, firmness, attractive color and resistance to pests and diseases; flavor has been secondary. Still, fresh strawberry consumption per capita has tripled in the past 30 years, to 5.3 pounds annually, and the United States is the world’s largest producer, with California dominating the market, accounting for 87 percent of the nation's crop.

What's missing most from commercial berries is fragrance, the original quality that gave the strawberry genus its name, Fragaria. To boost aroma, strawberry breeders, particularly in Europe, have long tried to cross alpine and musk varieties with cultivated ones, but with little success. Only in 1926 did scientists discover why the different species are not readily compatible: the wild and musk species have fewer sets of chromosomes than modern strawberries. As a result of this genetic mismatch, direct hybrids between these species typically produced few fruits, and these were often misshapen and had few seeds; the seeds in turn usually did not germinate, or produced short-lived plants.

Strawberry science took a big leap forward in Germany, starting in 1949, when Rudolf and Annelise Bauer treated young seedlings with colchicine, an alkaloid compound in meadow saffron, to increase the number of chromosomes in hybrids of alpine and common strawberries, producing new, genetically stable varieties. Over the years, some breeders have taken advantage of this method to create new hybrids, including a cultivar introduced last year in Japan that has large but soft pale pink fruit with a pronounced peach aroma. Such attempts have often run into dead ends, however, because the hybrids are not only soft but cannot be further crossed with high-performing modern varieties.

To be sure, there's still one place where the original musk strawberry survives in farm plantings, although on a very small scale: Tortona, between Genoa and Milan, where the Profumata di Tortona strawberry has been grown since the late 17th century. Cultivation peaked in the 1930s, and lingered into the 1960s, when the last field succumbed to urban development. Until a few years ago only a few very small plots existed in old-timers' gardens, but recently the municipal authorities, together with Slow Food, an organization devoted to preserving traditional foodways, started a program that has increased Profumata plantings to more than an acre, on nine farms. These pure musk berries are a luxurious delicacy, but they’re expensive to pick and very perishable—a prohibitive combination for commerce. In the United States, most growers would sooner raise wombats than fragile strawberries, no matter how highly flavored.

Swartz says he came to love strawberries as a child in the Buffalo, New York, gardens of his Polish-born grandparents. He majored in horticulture at Cornell, and after finishing his doctoral research in 1979 on apple dormancy, he started teaching at the University of Maryland and helped test experimental strawberry varieties with U.S. Department of Agriculture researchers Donald Scott, Gene Galletta and Arlen Draper—giants in the breeding of small fruits.

Swartz conducted trials for the 1981 release of Tristar, a small but highly flavored strawberry now revered by Northeastern foodies; it incorporates genes for extended fruiting from a wild berry of the Virginian species collected in Utah. But he chose to go his own way and concentrate on raspberries. Working with other breeders, and often using genes from exotic raspberry species, he has introduced eight raspberry varieties, of which several, such as Caroline and Josephine, proved quite successful.

Swartz, who is married to his college sweetheart, Claudia—she and their 23-year-old daughter, Lauren, have had raspberry varieties named after them—has been described by colleagues as a "workaholic," a "visionary" and a "lone wolf." For many years he participated in professional horticultural organizations, attending meetings and editing journals, but in 1996 he gave all that up to focus on fruit breeding. "I can't put up with a lot of academics," he says. To pursue opportunities as he saw fit, Swartz in 1995 formed a private company, Five Aces Breeding—so named, he says, because "we're trying to do the impossible."

Swartz is working on so many ventures that if he were younger, he says, he would be accused of having Attention Deficit Disorder. He's helping develop raspberries that lack anthocyanins and other phytochemicals, for medical researchers to use in clinical studies assessing the effectiveness of those compounds in fighting cancer. He's an owner of Ruby Mountain Nursery, which produces commercial strawberry plants in Colorado's San Luis Valley, possibly the highest—at an elevation of 7,600 feet—fruit-related business in the United States. He's got a long-term project to cross both raspberries and blackberries with cloudberry, a super-aromatic arctic relative of the raspberry. And he recently provided plants for a NASA contractor developing systems for growing strawberries on voyages to Mars.

His musk hybrid project relies on breakthroughs made by other scientists. In 1998, two Canadian researchers, J. Alan Sullivan and Bob Bors, allowed him to license their new strawberry hybrids, bred using colchicine, from a diverse range of wild species, including alpine and musk strawberries. (Sullivan and Bors, after years of experimentation, had created partially fertile musk hybrids with the requisite extra chromosomes.) Swartz's breeding strategies can be idiosyncratic. Like an athlete training at high altitude to boost his stamina, he deliberately chooses difficult growing environments (such as sultry Miami) for his test plots, so that successful varieties will be more likely to excel in more temperate commercial growing districts. His main challenge with the musk hybrids is to increase their size and firmness, so they can be picked and marketed economically. It's a trade-off. Strawberry plants produce limited amounts of photosynthates, which they use for high yield, firmness or sweetness. "You move one up, the others are going to move down," says Swartz, "and it's very rare that you can have all three qualities."

Walking the rows at his Miami test plot, Swartz shows me a puny, malformed fruit, which lacks seeds on one side. "That's what 99 percent of them used to look like a few generations ago," he says. "For years I'd be eating sterile, miserable things, nubbins with two or three seeds." The hormones produced by fertile seeds, he explained, are needed for proper development of the strawberry, which is actually a swollen receptacle, the end of the flower stalk. Still, he would grind up even the most unpromising fruits, take the few good seeds and grow them as parents for future generations.

Could he show me a large-fruited strawberry with full musk flavor? Through seven years of crossing the original Canadian hybrids with cultivated varieties, the musk genes have become increasingly diluted, and it has been hard to retain the sought-after aroma. Typically, only one in 1,000 seedlings offers it, and I've heard that he's nervous we might not find any that do.

But after an hour or so, he picks a medium-sized, conical berry and bites into it. "That's moschata!" From the same plant I choose a dead-ripe fruit. It has an almost mind-bogglingly powerful, primeval aroma. Swartz ties an orange ribbon around the plant, to mark it for use in future crosses, and beams like an alchemist who has found the philosopher's stone.

By late afternoon it's pleasantly balmy, but Swartz is wearing down. He says his knees ache. His fingers are stained winy red. "I'm starting to lose it, frankly," he says. "I've had too many strawberries." What would drive him to spend his own money and more than a decade tasting roughly 100,000 berries, many of them dreadful, with the prospects for reward uncertain? "It's just a stupid donkey attitude—I've got to do this or else there's no reason for me to do anything. I have the religion of moschata."

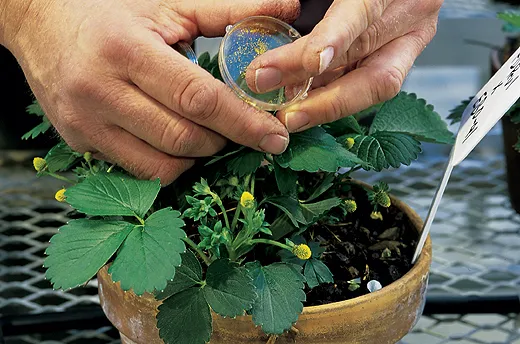

By the second morning of my Florida visit, Swartz has identified three musk hybrids with promising characteristics. From one plant, he clips runners and wraps them in moist paper towels; he'll take them back to his greenhouse in Maryland and propagate them into genetically identical offspring—clones. From another plant he plucks unopened flowers, pulls off the pollen-coated anthers and drops them into a bag, for direct use in pollinating other plants to make new crosses. "It's really cool," he says. "After seven years of hard work, I can actually eat this and show people—here's a large-sized fruit with this flavor."

This past spring, Swartz says he made further progress at a test plot in Virginia after he crossed a bland commercial strawberry with his hybrids and obtained more new plants with good moschata flavor. Swartz says he's about three or four years from developing a musk hybrid with commercially competitive yield, size and shelf life. Still, he may have a hard time bucking the American fruit marketing system's demand for varieties that appeal to the lowest common denominator of taste. But he has always been motivated less by financial gain than by curiosity, the promise of a bit of adventure—and a touch of obsession. "I really don't care if this works or not, it's just so much fun getting there," he says. "When it happens, it'll be, 'I've found the holy grail, now what do I do with it?'"

David Karp, a freelance writer and photographer specializing in fruit, is working on a book about fruit connoisseurship.