One spring day in 2005, a yellow school bus carrying six passengers turned onto a freshly paved driveway seven miles southeast of downtown Des Moines, Iowa. Passing beneath a tunnel of cottonwood trees listing in the wind, it rumbled past a life-size sculpture of an elephant before pulling up beside a new building. Two glass towers loomed over the 13,000-square-foot laboratory, framed on three sides by a glittering blue lake. Sunlight glanced off the western tower, scrunching the faces pressed to the windows of the bus. Only three of them were human.

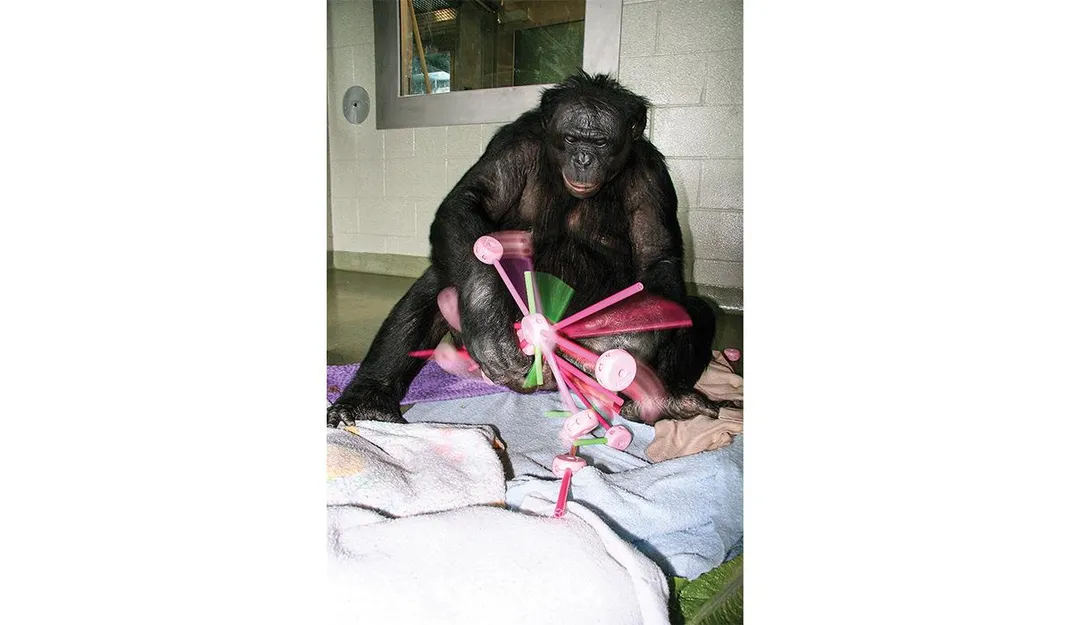

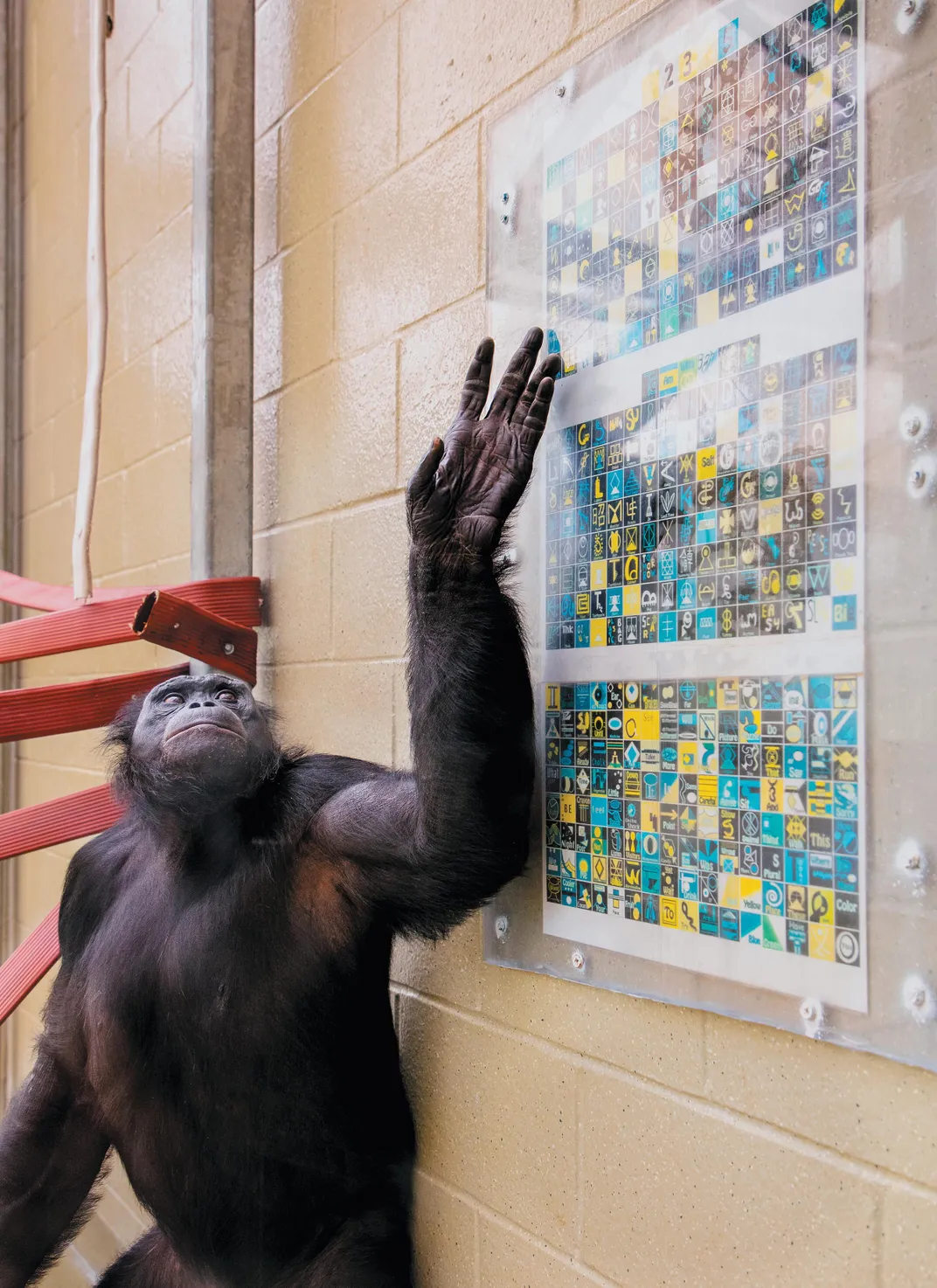

When the back door swung open, out climbed Sue Savage-Rumbaugh, her sister and collaborator Liz Pugh, a man named William Fields, and three bonobo apes, who were joining a group of five bonobos who had recently arrived at the facility. The $10 million, 18-room compound, known then as the Great Ape Trust, bore little resemblance to a traditional research center. Instead of in conventional cages, the apes, who ranged in age from 4 to 35, lived in rooms, linked by elevated walkways and hydraulic doors they could open themselves. There was a music room with drums and a keyboard, chalk for drawing, an indoor waterfall, and a sun-washed greenhouse stocked with bananas and sugar cane. Every feature of the facility was designed to encourage the apes’ agency: They could help prepare food in a specialized kitchen, press the buttons of a vending machine for snacks, and select DVDs to watch on a television. A monitor connected to a camera outside allowed the bonobos to screen human visitors who rang the doorbell; pressing a button, they granted or denied visitors access to a viewing area secured by laminated glass. But the center’s signature feature was the keyboard of pictorial symbols accessible on computerized touchscreens and packets placed in every room and even printed on researchers’ T-shirts. It consisted of more than 300 “lexigrams” corresponding to English words—a lingua franca that Savage-Rumbaugh had developed over many years to enable the bonobos to communicate with human beings.

Before Savage-Rumbaugh began her research, the bonobo, an endangered cousin of the chimpanzee, was little known outside the Congo River Basin. Savage-Rumbaugh’s seven books and close to 170 articles about their cognitive abilities played a significant role in introducing them to the wider world. Her relationship with a bonobo named Kanzi, in particular, had made the pair something of a legend. Kanzi’s aptitude for understanding spoken English and for communicating with humans using the lexigrams had shown that our hominid kin were far more sophisticated than most people had dared to imagine.

By the time Kanzi arrived at the Great Ape Trust that day in 2005, his name had appeared in the Encyclopedia Britannica. In 2011, Time magazine named Savage-Rumbaugh one of the world’s 100 most influential people on the basis of her work with Kanzi and his family. None other than Frans de Waal, the world’s pre-eminent primatologist, lauded her unique experiment. Her research had “punched holes in the wall separating” humans from apes, he wrote—a wall built upon the longstanding scientific consensus that language was humanity’s unique and distinguishing gift.

In November 2013, eight years after she opened the Trust, and having made plans for a phased retirement, Savage-Rumbaugh returned to Des Moines from a medical absence to care for Teco, Kanzi’s 3-year-old nephew, who had injured his leg. The atmosphere was unusually tense. After a strained email exchange that continued for several days, the chair of the facility’s board finally told her that she could no longer stay at the Trust. Still concerned about Teco, Savage-Rumbaugh refused to leave, but, the next day, she complied once the young bonobo was in the hands of another caretaker. “When you depart, please leave your access card and any keys with whomever is on duty right now,” the chairman wrote to her.

Bewildered, Savage-Rumbaugh retreated to the cottage she rented next door. Then she contacted a lawyer. What followed was a prolonged—and ongoing—custody battle unique in the history of animal research and in the movement for animal rights. At its heart is a question that continues to divide primatologists: What constitutes legitimate research into the inner lives of apes?

I learned about the bonobos by accident. I was an MFA student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, in Iowa City, writing a novel that featured a scientist who studied birdsong. One afternoon my teacher, the novelist Benjamin Hale, called me into his office. If I was interested in language and animals, he said, there was a place in nearby Des Moines that I needed to see. He had visited several years earlier, while researching his novel The Evolution of Bruno Littlemore, about a chimpanzee who learns to speak. He told me that the place was run by a brilliant but polarizing psychologist named Sue Savage-Rumbaugh, and he gave me her contact information.

I emailed Savage-Rumbaugh. By then I’d read about the numerous awards she had received, and about the fiery debates her research had sparked in fields as far-flung as linguistics and philosophy. So I was surprised when she replied to say that her 30-year experiment had ended. Kanzi and his relatives were still living at the center, she told me. She could hear them from her cottage next door.

We arranged to meet for lunch. Because I didn’t have a car, we settled on a diner in Iowa City, two hours from Savage-Rumbaugh’s home in Des Moines. When I arrived, Savage-Rumbaugh was already seated at a booth in the back corner, wearing a stained button-down shirt, purple pants and a safari hat. Half of her right forefinger was missing: bitten off, she later said, by a frightened chimp she’d met in graduate school.

“I hope you don’t mind,” she said in a silvery voice, indicating her Caesar salad. She was 69 but looked younger, her warm green eyes peering out cautiously from underneath a mop of straight white hair.

I asked Savage-Rumbaugh what made her experiment different from other studies of ape intelligence. “Experimental psychologists typically assume that there is a major difference between ourselves and apes that is not attributable to environmental factors,” she said. “The difference in my work is that I never made that assumption.”

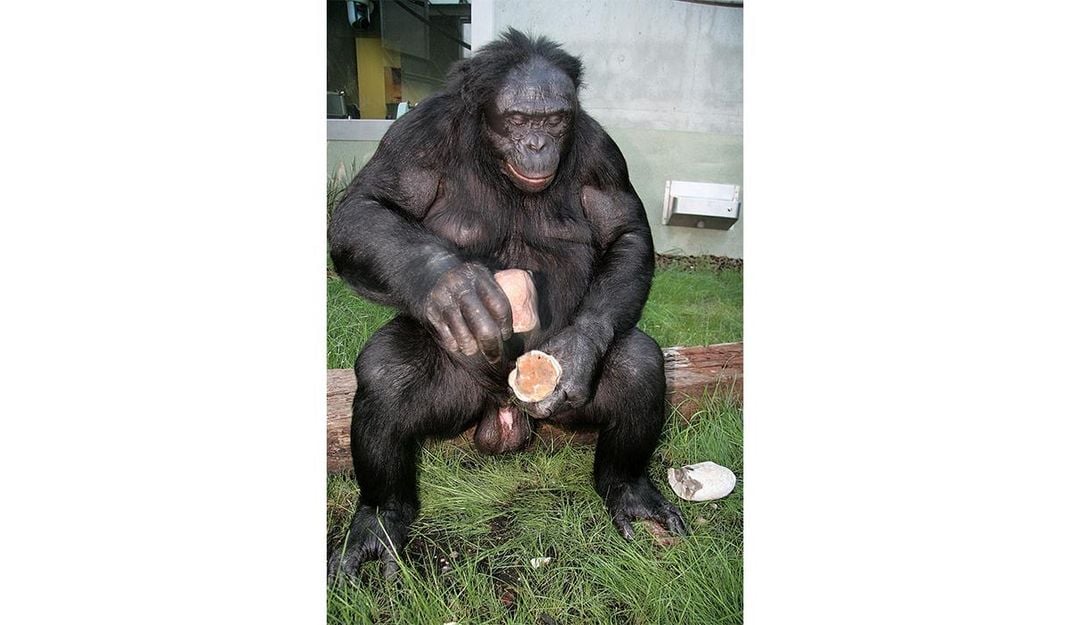

Like renowned field primatologists Dian Fossey and Jane Goodall, Savage-Rumbaugh interacted with the apes that she studied, but she’d done so in the confines of a lab, where scientists typically maintain an emotional distance from their animal subjects. And unlike Fossey and Goodall, Savage-Rumbaugh had gone so far as to integrate into the group, co-rearing a family of bonobos over the course of several decades and engaging them in human ways of life. In 2015, her findings—that the apes in her care could recognize their own shadows, learn to enter into contractual agreements, signal intent, assume duties and responsibilities, distinguish between the concepts of good and bad, and deceive—were used in a historic lawsuit that helped curtail biomedical testing on great apes in the United States. The findings also raised a fascinating, provocative and deeply troubling question: Can an animal develop a human mind?

“It’s a question you don’t ask,” Savage-Rumbaugh said. “A lot of people, a lot of scientists, don’t want that kind of study done. Because if the answer were yes...” Her eyes sparkled. “Then, oh my god—who are we?”

* * *

She never planned to study bonobos. The oldest of seven children born to a homemaker and a real estate developer in Springfield, Missouri, Sue Savage became fascinated by how children acquire language while she was teaching her siblings to read. At Southwest Missouri University, she studied Freudian psychology and its counterpoint, behaviorism, B.F. Skinner’s theory that behavior is determined by one’s environment rather than by internal states such as thinking and feeling. She won a fellowship to study toward a doctorate at Harvard with Skinner himself, but turned it down to work with apes at the University of Oklahoma’s Institute for Primate Studies, where the field of “ape language” was enjoying its heyday. She wrote her doctoral dissertation on nonverbal communication between mother and infant chimpanzees. At a symposium in 1974, she delivered a paper critiquing colleagues’ attempts to teach American Sign Language to chimps. By focusing on what the apes signed, she argued, researchers were neglecting what they were already “saying” through their gestures and vocalizations, a view that earned her the nickname “the Unbeliever.”

Six months later, her phone rang. It was Duane Rumbaugh, the psychologist who had invited her to speak at the symposium. A position had opened up at Georgia State University, he said, with connections to the Yerkes Primate Research Center, in Atlanta, the oldest institute in the United States for the study of nonhuman primates. The center was acquiring several chimplike hominids called bonobos from the forests of the Congo River Basin, in what was then Zaire. Was Savage-Rumbaugh interested?

She didn’t have to think twice. Very little had appeared about bonobos in the scientific literature, but some researchers regarded them as a close living model of early humans. In their gait and facial structure, they resembled Australopithecus, a group of apes that went extinct about two million years ago and are believed to be among the ancestors of humankind. In time, research on free-living bonobos would reveal that they have a matriarchal social structure and that—unlike chimps and humans—they almost never kill one another. Savage-Rumbaugh accepted the position and packed her bags for Atlanta.

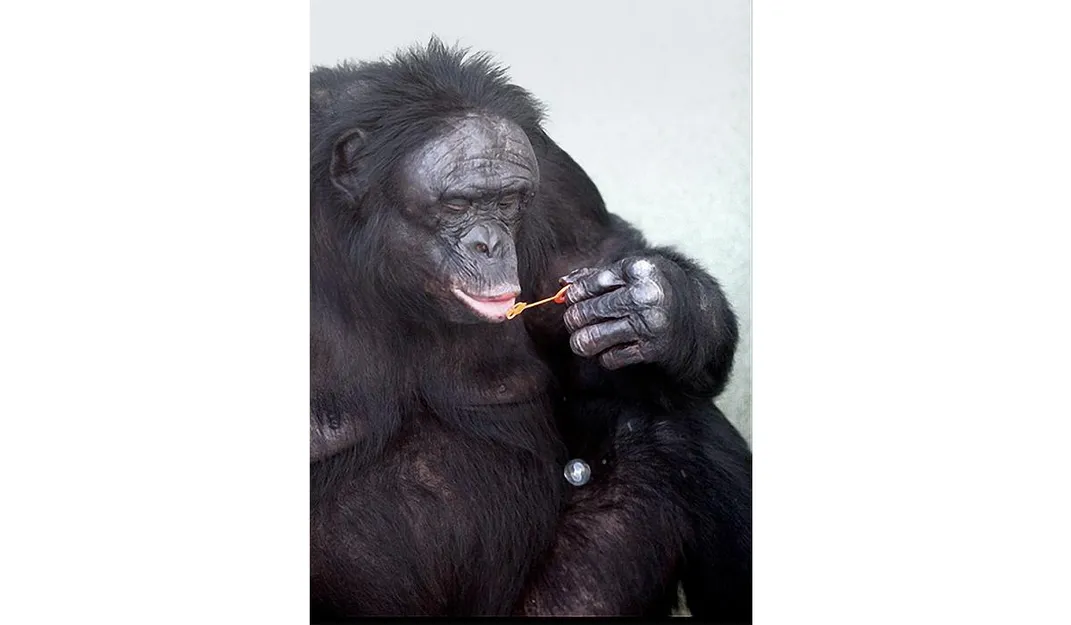

Sure enough, the bonobos were eerily humanlike. They often rose up to walk on two legs, and responded to subtle changes in human caretakers’ facial expressions. While the chimpanzees used their feeding pails as props in aggressive displays, the bonobos found a variety of nonviolent uses for them: a toilet, a container for drinking water, a hat. On one occasion, Savage-Rumbaugh observed Kanzi’s father carry his pail to the corner of his cage from which he could see the shrieking chimps. He turned it over and sat there with his elbows on his knees, watching them.

In the spring of 1981, the Rumbaughs, now married, negotiated the transfer of 6-month-old Kanzi and his adoptive mother, Matata, away from planned biomedical studies at Yerkes to live at the nearby Language Research Center, a facility they had established in collaboration with Georgia State University to explore the apes’ cognitive abilities. There, Savage-Rumbaugh introduced Matata to an early version of the lexigram keyboard, which had helped enable some developmentally challenged children to communicate. While Kanzi frolicked around the lab, Savage-Rumbaugh would sit beside his mother, hold up an object such as a sweet potato or a banana, and touch the corresponding symbol on a keyboard, indicating that Matata should press it herself. The training went nowhere. After two years, researchers temporarily called Matata back to Yerkes for breeding. By then Savage-Rumbaugh had despaired of collecting any publishable data on Matata, but she suspected she’d have more luck with the infant.

Matata’s absence consumed Kanzi. “For three days, the only thing he wanted to do was to look for Matata,” Savage-Rumbaugh recalled. “We looked—was she under this bush, was she under there? After looking in the forest, he looked every place in the lab that she could possibly hide.” Exhausted, little Kanzi wandered over to a keyboard. Extending a finger, he pressed the key for “apple,” then the key for “chase.” Then he looked at Savage-Rumbaugh, picked up an apple lying on the floor, and ran away from her with a grin on his face. “I was hesitant to believe what I was seeing,” Savage-Rumbaugh told me. Kanzi had evidently absorbed what his mother had not. He used the keyboard to communicate with researchers on more than 120 occasions that first day.

Savage-Rumbaugh rapidly adjusted her framework to encourage this capacity in Kanzi. She expanded the lexigram keyboard to 256 symbols, adding novel words for places, things and activities that seemed to interest him, such as “lookout point,” “hide” and “surprise.” Rather than engage him in structured training sessions, she began using the lexigrams with him continually throughout the day, labeling objects and places all over the 55-acre property and recording what he “said” while out exploring. Seventeen months later, the young bonobo had acquired a vocabulary of 50 words. One study in 1986 showed that more than 80 percent of his multi-word statements were spontaneous, suggesting that he was not “aping” the gestures of humans but was using the symbols to express internal states of mind.

By Kanzi’s fifth birthday, he had made the front page of the New York Times. Most startling to the parade of scientists who came to Georgia to evaluate him was his comprehension of some spoken English. Kanzi not only correctly matched spoken English words to their corresponding lexigrams—even while placed in a separate room from the person speaking, hearing the words through headphones—but he also appeared to grasp some basic grammar. Pointing to “chase,” then “hide,” and then to the name of a human being or bonobo, he would initiate those activities with his interlocutor in that order.

In a landmark study in the mid-1990s, Savage-Rumbaugh exposed Kanzi to 660 novel English sentences including “Put on the monster mask and scare Linda” and “Go get the ball that’s outside [as opposed to the ball sitting beside you].” In 72 percent of the trials, Kanzi completed the request, outcompeting a 2½-year-old child. Yet his most memorable behavior emerged outside the context of replicable trials. Sampling kale for the first time, he called it “slow lettuce.” When his mother once bit him in frustration, he looked mournfully at Savage-Rumbaugh and pressed, “Matata bite.” When Savage-Rumbaugh added symbols for the words “good” and “bad” to the keyboard, he seized on these abstract concepts, often pointing to “bad” before grabbing something from a caregiver—a kind of prank. Once, when Savage-Rumbaugh’s sister Liz Pugh, who worked at the Language Research Center as a caregiver, was napping, Kanzi snatched the balled-up blanket she’d been using as a pillow. When Pugh jolted awake, Kanzi pressed the symbols for “bad surprise.”

* * *

To some scientists, Kanzi’s intellectual feats demonstrated clearly that language was not unique to human beings. But others were unimpressed. “In my mind this kind of research is more analogous to the bears in the Moscow circus who are trained to ride unicycles,” said the Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker. To him, the fact that Kanzi had learned to produce elements of human communication didn’t imply that he had the capacity for language. Thomas Sebeok, a prominent linguist who organized a conference in 1980 that helped squelch public funding for animal language research, had a similar take. “It has nothing to do with language, and nothing to do with words,” he said, when asked to comment on Savage-Rumbaugh’s work. “It has to do with communication.”

The controversy masked an uncomfortable truth: No one agreed on what the difference between language and communication actually was. The distinction goes back to Aristotle. While animals could exchange information about what they felt, he wrote, only humans could articulate what was just and unjust, and this made their vocalizations “speech.” In the 1600s, the philosopher René Descartes echoed this idea: While animals jabbered nonsensically, he wrote, God had gifted human beings with souls, and with souls language and consciousness. In the modern era, the influential linguist Noam Chomsky theorized that human beings possess a unique “language organ” in the brain. While human languages might sound and look different from one another, Chomsky wrote in the 1960s, all of them are united by universal rules that no other animal communication system shares. According to Chomsky’s early work, this set of rules distinguishes the sounds and gestures we make when we talk from the dances of bees, the twittering of birds and the spectral keening of whales. It’s the magic ingredient that makes our languages uniquely capable of reflecting reality.

Today, many contemporary experts trace speech not to a pattern common to all human languages, but rather to what the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein called a “form of life”—the combination of vocalizations and rituals that overlap to produce a shared culture. That Kanzi began to use the lexigrams to communicate without previous direct training suggested that he was building a novel “form of life” with the researchers studying him. Their interactions, which grew more complex with time, implied to many researchers that language was not a biological endowment but a dynamic social instrument, accessible by brains that weren’t human.

Kanzi’s aptitudes raised a tantalizing question: Had sustained exposure to human culture since infancy physically transformed his brain, or had it tapped into a capacity free-living bonobos were already exercising among themselves, unbeknownst to us? To explore this possibility, in 1994 Savage-Rumbaugh spent several months studying bonobos in the Luo Scientific Reserve in the Democratic Republic of Congo. “I almost didn’t come back,” she told me. “If it hadn’t been for my attachment to Duane and Kanzi and Panbanisha [Kanzi’s younger sister], I would have happily stayed.”

Back in Georgia, the bonobos were growing more sophisticated. Panbanisha was starting to exhibit capabilities that equaled Kanzi’s, confirming that he wasn’t simply an ape savant. Savage-Rumbaugh spent most of her time in their quarters. She increasingly communicated with them via high-pitched vocalizations and gestures in addition to the lexigram keyboards, and when the bonobo females needed help with a newborn, she slept alongside them. The bonobos’ behavior changed. They began making more declarative statements—comments and remarks—contradicting previous research suggesting that captive great apes were capable only of mimicry or of making requests. By the early 2000s, Savage-Rumbaugh published images of geometric figures drawn in chalk by Panbanisha, each corresponding roughly to a lexigram.

Even more startlingly, however, the bonobos were exhibiting the ability to lie. “A common strategy was to send me out of the room on an errand,” Savage-Rumbaugh wrote in the book Machiavellian Intelligence, a collection of academic papers about the role of social experience in the evolution of human intellect, “then while I was gone she [Matata] would grab hold of something that was in someone else’s hands and scream as though she were being attacked. When I rushed back in, she would look at me with a pleading expression on her face and make threatening sounds at the other party. She acted as though they had taken something from her or hurt her, and solicited my support in attacking them. Had they not been able to explain that they did nothing to her in my absence, I would have tended to side with Matata and support her as she always managed to appear to have been grievously wronged.” Deception in primates had been reported before, but this was something new. Matata was doing more than lying to Savage-Rumbaugh. She was attempting to manipulate her into a false belief that a colleague had done something “wrong.”

* * *

In the early 2000s, Duane Rumbaugh got a call from a man named Ted Townsend, an Iowa meat processing magnate and wildlife enthusiast who had read about the bonobos and wanted to visit the Language Research Center. Savage-Rumbaugh, who was director of the center’s bonobo project, agreed to host him. When he arrived, Kanzi looked at him and gestured at the woods, indicating that he wanted to play a game of chase. They did, and then Kanzi went to the keyboard and asked for grape juice. Townsend tossed him a bottle, at which point Kanzi touched the symbol for “thank you.”

“My world changed,” Townsend told the Des Moines Register in 2011. “I realized that a nonhuman life form experienced a concept. That was not supposed to be possible.”

Townsend had a proposal for Savage-Rumbaugh. How would she feel about a state-of-the-art sanctuary designed specifically for her research? He would recruit top architects to execute her vision. They would build it on a 230-acre property outside Des Moines, on the grounds of a former quarry.

It was a windfall. Funding was precarious at the Language Research Center, where Savage-Rumbaugh had to reapply for grants every few years. She wanted to study bonobos across generations, and Townsend was promising long-term support for her work. In addition, her marriage had ended. So she abandoned her tenured professorship at Georgia State University and accepted Townsend’s offer.

That was how Savage-Rumbaugh came to live in Des Moines with eight bonobos, her sister Liz Pugh, and William Fields, a custodian and student in anthropology at the Georgia State lab who had developed a close bond with the apes and would later author 14 papers and one book with Savage-Rumbaugh. As she had at the Language Research Center, Savage-Rumbaugh slept at the sanctuary from time to time. In 2010, she moved in with the bonobos full time, helping Panbanisha soothe her infants when they woke in the night and writing her papers on a laptop as they dozed.

It was in this unique environment, where Savage-Rumbaugh worked until 2013, that the foundations of her experiment began to shift. “It developed spontaneously as we tried to live together during the past two decades,” she wrote of what she called a hybrid “Pan/Homo” culture shared by the apes and their human caretakers. (“Pan” referred to the ape genus comprised of bonobos and chimps, while “Homo” referred to the genus including modern Homo sapiens as well as extinct human species such as Neanderthals.) While outsiders perceived the apes’ vocalizations as inarticulate peeps, the human members of this “culture” began to hear them as words. Acoustic analyses of the bonobos’ vocalizations suggested that the people weren’t hearing things: The vocalizations varied systematically depending on which lexigram the bonobo was pressing. In effect, the apes were manipulating their vocalizations into a form of speech.

The bonobos grew impatient with the tests. “Each visitor wants a practical demonstration of the apes’ language,” Savage-Rumbaugh wrote in the book Kanzi’s Primal Language, authored with Fields and the Swedish bioethicist Pär Segerdahl, “and therefore we often have to treat the apes, in their own home, as if they were trained circus performers.” In the book Segerdahl recounts how, when he failed to heed a staff member’s request that he lower his voice in the presence of the apes, Panbanisha pressed the lexigram for “quiet.” That same day, Panbanisha’s young son Nathan poked his arm through a tube in the glass wall separating the visitors’ area from the apes’ quarters, and Segerdahl reached out and touched his hand. After the bonobo fled to his mother, Segerdahl writes, Panbanisha charged up to the glass where he was sitting, keyboard in hand, and held her finger over the symbol for “monster.” “It was a bit like being struck by the mystery of your own life,” Segerdahl told me in an email about the encounter. “Panbanisha made me realize that she was alive, as mysteriously alive as my own human aliveness.”

Even for insiders, however, the “Pan/Homo” world wasn’t always copacetic. One afternoon, Kanzi entered the viewing area and saw an unfamiliar woman on the other side of the sound-permeable glass window. The stranger, a scientist, was arguing with Savage-Rumbaugh about how best to archive video footage.

Kanzi, evidently upset, banged on the glass. Noticing this, Fields, who had been working in his office nearby, came over to ask him what was wrong.

“He wanted me to go over there and stop her [the visiting scientist] from doing this,” Fields told the public radio program “Radiolab” in 2010. Kanzi used his lexigram keyboard to say that it was Fields’ responsibility to “take care of things, and if I didn’t do it, he was going to bite me.”

“I said, ‘Kanzi, I really can’t go argue, I can’t interfere.’ I defaulted to the way things would happen in the human world.”

The following day, when Savage-Rumbaugh was leaving the bonobos’ enclosure, Kanzi made good on his promise. He slipped past her, ran down the hall to Fields’ office, and sank his teeth into his hand.

Fields didn’t interact with Kanzi for eight months, until finally another staff member approached Fields and said, “Kanzi wants to tell you he’s sorry.”

Kanzi was outside at the time. Fields recalled leaving the building, keyboard in hand, and approaching the mesh enclosure where Kanzi was sitting. “As soon as I got down there he threw his body up against the wire, and he screamed and screamed a very submissive scream. It was clear he was sorry, and he was trying to make up with me. I asked him on the keyboard if he was sorry, and he told me yes.”

* * *

Waking up day after day to light slanting onto the bonobos, asleep in their nests of carpets, Savage-Rumbaugh faced an uncomfortable truth. No matter how she looked at it, the apes’ autonomy at the Iowa facility was a sham. A fence prevented them from traveling beyond their makeshift outdoor “forest.” The button she had installed so they could screen incoming visitors was ultimately for show; human employees could override it. She could leave when she wanted—to shop, to travel, to spend a night in the cottage she rented next door. But when evening fell, the apes were ushered into their quarters and locked in. Outside was a planet dominated by a species that viewed them as curiosities—close enough to human beings to act as our biological proxies in medical research, but not close enough to warrant meaningful rights. And she was complicit.

“They’re always going to be discriminated against every moment of their lives, and I allowed them to be born in a situation which created that,” Savage-Rumbaugh said in a 2018 interview archived at Cornell University. “And then they grew up to know that I created that. How can one cope with that? There’s no coping. There’s no intellectual way to make it right.”

She contacted officials in Congo, hoping to return the apes to a sanctuary not far from where Matata had been captured. But Matata had spent most of her adult life in human custody. Her children and grandchildren, including Kanzi and Panbanisha, born in confinement, had never set foot in a rainforest. The plan never came together.

In an audacious paper in the Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, Savage-Rumbaugh published a withering critique of prevailing standards for the thousands of apes kept in zoos worldwide. “We wish to create good feelings in ourselves by giving objects, trees, and space to our captive apes,” she wrote, “but we continue to take from them all things that promote a sense of self-worth, self-identity, self-continuity across time, and self-imposed morality.”

To bolster her case, Savage-Rumbaugh cited a list of conditions that were important to a captive ape’s welfare, including the ability to explore new places and spend time alone. But her boldest act was to describe how she’d constructed the list: by interviewing the bonobos in her care, three of whom she listed as the paper’s co-authors: Kanzi Wamba, Panbanisha Wamba and Nyota Wamba (“Wamba” is the name of a village in the Luo Scientific Reserve where bonobos were first studied). The choice was “not a literary technique,” Savage-Rumbaugh wrote, “but a recognition of their direct verbal input to the article.”

The paper did not go over well. To many primatologists, the implication that the bonobos could contribute intellectually to an academic article strained credulity. “That paper damaged her credibility,” Robert Seyfarth, an esteemed primatologist and emeritus professor at the University of Pennsylvania, told me. Barbara King, an emerita professor of anthropology at the College of William and Mary, who has interacted with Kanzi and has written books such as How Animals Grieve and Personalities on the Plate: The Lives & Minds of Animals We Eat, echoed Seyfarth. “I’m not skeptical that these bonobos are sentient. Of course they are, and incredibly intelligent and attuned to their own needs, and able to communicate with us in fascinating ways. But I don’t think the methods in that paper have much validity.” She added: “I think we need to acknowledge that they are keenly intelligent animals without forcing them to be what they are not—capable of discussing these issues.”

The bonobos, meanwhile, occasionally used the keyboards to indicate to Savage-Rumbaugh that they had been harmed by a staff member. When this had happened before, the staff member would defend him- or herself, and Savage-Rumbaugh would try to de-escalate the conflict. Gradually, however, the staff felt that Savage-Rumbaugh’s allegiances began to shift. She no longer seized on the conflict as evidence of the bonobos’ capacity for Machiavellian behavior.

“She started accusing us of things we wouldn’t ever do,” a former caretaker told me. In one such instance, the caretaker said Savage-Rumbaugh blamed her for cutting Kanzi across the chest after misinterpreting a conversation she’d had with Kanzi using the lexigrams; in fact, he’d evidently hurt himself on a fence the caretaker had faultily repaired.

When I asked the caretaker (who asked to remain anonymous) how the bonobos behaved during confrontations, she said: “They’d always try to calm Sue down, to groom her or distract her or sit down with them. I think they just wanted everybody to get along.”

* * *

In 2008, torrential rains engulfed Des Moines, flooding the sanctuary. In the wake of that disaster and the global financial crisis, Townsend announced he would reduce his $3 million annual contribution to the facility by $1 million a year, withdrawing fully by 2012. Staff salaries evaporated. Savage-Rumbaugh used her retirement savings to keep the lights on, while steadily alienating the few remaining employees. In 2012, she fired a longtime caretaker. The staff responded by releasing a public letter to the facility’s board, alleging that Savage-Rumbaugh was mentally unfit to care for the apes. Because of her negligence, they claimed, the bonobos had on several occasions been put in harm’s way: They spent a night locked outdoors without access to water, had burned themselves with hot water carelessly left in a mug, and had been exposed to unvaccinated visitors. Once, the staff alleged, Savage-Rumbaugh’s carelessness had nearly resulted in the escape of Panbanisha’s son, Nyota, from the facility. The staff also informed the board that biologically related bonobos had copulated, unnoticed, leading to an unplanned pregnancy that resulted in a miscarriage. Savage-Rumbaugh denied the allegations. An internal investigation cleared her of wrongdoing (whether the alleged mishaps actually occurred was never made public), and a subsequent inspection by the U.S. Department of Agriculture gave the facility itself a clean bill of health.

Then one day in spring 2013, Savage-Rumbaugh collapsed in her bedroom at the facility. “She was just exhausted, I think,” Steve Boers, who succeeded Savage-Rumbaugh as executive director, told me. “Just fell down from exhaustion and depression. I think she felt like she was on her own there, and everyone was against her.”

Having sustained a concussion from the fall, Savage-Rumbaugh flew to New Jersey to discuss a succession plan with Duane Rumbaugh, with whom she remained close. On Rumbaugh’s suggestion, she contacted one of her former students, Jared Taglialatela, a biologist at Kennesaw State University, to ask if he would be willing to take over as director of research. The bonobos liked Taglialatela. He and Savage-Rumbaugh had written a dozen papers and book chapters together, including one describing the bonobos’ spontaneous drawings of lexigrams.

Savage-Rumbaugh says she believed Taglialatela would continue her “research trajectory” when he took up his post. Written agreements from 2013 formalizing the Great Ape Trust’s co-ownership of the bonobos with several other entities described what the ownership, custody and care of the apes entailed, including engaging them with “language and tools” and exposing them to other “human cultural modes.” In addition to providing the apes with the life that some of them had known for 30 years, the protocol had a scientific rationale: It was intended to reveal whether the apes would teach these behaviors to their offspring, thereby exhibiting an aptitude for cultural transmission thought unique to humankind.

This is why Savage-Rumbaugh says she was blindsided when she returned to the lab in November 2013, after a six-month absence, to find herself ordered off the premises. (Some board members feared that her return in an active capacity would jeopardize several potential new research hires, including Taglialatela.)

Savage-Rumbaugh left the building. Not long afterward, her sister, Liz, who continued to work with the bonobos for a time, reported that things were changing at the facility. Derek Wildman, a professor of molecular physiology at the University of Illinois who had mapped Kanzi’s genome, returned to find what he later described in court as a “ghost town.” From his perspective, the new leadership team was more interested in “standard psychological experiments” than in the interactive, cultural and familial approach pioneered by Savage-Rumbaugh. Laurent Dubreuil, a professor of comparative literature and cognitive science at Cornell, who had visited the bonobos in Iowa on two occasions during Savage-Rumbaugh’s tenure and returned in 2014, testified that the apes’ access to the keyboards had been reduced. He said that Boers, the new executive director, explained to him that the staff was aiming to “put the bonobo back in the bonobo.”

In 2015, Savage-Rumbaugh sued for breach of contract. Jane Goodall submitted a letter in support of Savage-Rumbaugh’s continued involvement with the apes. Even the Democratic Republic of Congo, which technically owned Matata according to the 2013 agreements, wrote on Savage-Rumbaugh’s behalf: “If for any reason [Savage-Rumbaugh] continues to be banned from access, the DRC will need to assert its ownership interest and take charge of the bonobos,” the country’s minister of scientific research wrote to the court.

Taglialatela took the witness stand at a federal courthouse in Des Moines in May 2015. He testified that while he found Savage-Rumbaugh’s discoveries “profound,” he had come to view her experiment as unethical. He compared his former mentor to Harry Harlow, a psychologist notorious for studying maternal deprivation in monkeys; in one experiment, Harlow separated infant monkeys from their mothers and used a wire rack outfitted with a nipple to feed them. “We found out it is devastating to the emotional and neurological development of an organism when we do that type of thing,” Taglialatela said. “That was his work, and it was really important that we all learned that. But if a person came to you and said, ‘Hey, could we do that again,’ you would probably say no, right?” He paused. “I disagree with the idea of taking a bonobo even for part of the day, rearing it with humans, for any reason, because I think that the detriment to the individual animal is not justified by the benefit you get from the science.”

The judge deliberated for five months. During that time, a New York court denied a case to extend legal “personhood” to great apes filed in part on the strength of an affidavit written by Savage-Rumbaugh on bonobos’ capacities. Then, in November 2015, came the decision in Savage-Rumbaugh’s case: “Perhaps the bonobos would be happier and their behavior productively different with Dr. Savage-Rumbaugh and her direct contact, familial association with them than they are in the current environment in which staff and researchers do not assume a quasi-parental role,” the judge wrote. “The Court is not in a position to decide what kind of relationship with humans is best for the bonobos or to advance the research on their human-like abilities.”

He denied Savage-Rumbaugh’s motion to resume her research. While the 2013 agreements described Savage-Rumbaugh’s methods, they did not, owing to the precise language used in the contracts, oblige Taglialatela to continue those methods. As for a larger dispute over who owned several of the bonobos, including Kanzi, the court had no jurisdiction in the matter. For that, Savage-Rumbaugh would need to take her case to state court.

In an email to me, Frans de Waal, the primatologist, described the case as emblematic of a deeper conundrum in the study of animal minds: “Work with Kanzi has always lived somewhere between rigorous science and social closeness and family life,” he wrote. “Some scientists would like us to test animals as if they are little machines of which we only need to probe the responses, whereas others argue that apes reveal their full mental capacities only in the sort of environment that we also provide for our children, with intellectual encouragement among loving adults. There is some real tension between these two views, because loving adults customarily overestimate what their charges are capable of and throw in their own interpretations, which is why children need to be tested by neutral psychologists and not the parents. For Kanzi, too, we need this middle ground between him feeling at ease with those around him and being tested in the most objective way. The conflict around Kanzi’s custody is a fight between both sides in this debate.”

* * *

I finally got the chance to meet Kanzi last July. A storm was gathering. From downtown Des Moines, I drove my rental car past vinyl-sided houses and a presbytery, until I reached a sign printed with a blown-up image of Kanzi’s face. As I drove past it, down the tree-lined driveway, a faded elephant’s trunk poked out of the foliage. It was the statue Ted Townsend had installed years ago, claimed now by the woods.

Four years had passed since the trial. Savage-Rumbaugh’s efforts to bring her case to state court hadn’t come together and, discouraged, she had moved to Missouri to care for her dying mother. She hadn’t been allowed back into the facility in more than five years, but her lawyer and a former colleague had both visited a few years earlier. They told me separately that when Kanzi appeared in the viewing area, he approached a keyboard and touched the key for “Sue.”

As the first drops of rain pricked my windshield, a high, clear voice like a screeching tire rose from the complex up ahead. My stomach dropped. It was a bonobo. The apes must have been outside, then, in the snarled greenery between the building and the lake. I looked for motion in the grass but saw nothing.

Taglialatela emerged as I was getting out of my car. Wearing sneakers and cargo pants, he seemed friendly if a little nervous as he shook my hand, his brown eyes darting between mine. We could chat for a while, he said, and then he would show me around. They had just acquired a new bonobo, Clara, from the Cincinnati Zoo, to help balance the gender dynamics among the apes. She seemed to be acclimating well.

He opened the heavy metal door leading into the facility. We entered the lobby, a low-ceilinged space hung with painted portraits of the bonobos. A couch in one corner faced an empty room encircled by laminated glass. Inside was a small ledge positioned beneath a blank touchscreen I recognized from a segment on “The Oprah Winfrey Show.” In that footage, Kanzi sits on the ledge beside Savage-Rumbaugh, pressing lexigram symbols on the screen to communicate.

I asked Taglialatela if it was true that under his leadership the facility had transitioned away from Savage-Rumbaugh’s interactive approach to studying ape cognition.

He nodded. “That kind of getting up close nowadays is considered, like—” He made a slicing motion across his throat. “Being in the same space with them is potentially dangerous. It’s risky to them, it’s risky to the person doing it, and I can’t think of a scientific value that would justify that risk.”

I glanced over his shoulder at the door separating the lobby from the corridor leading to the ape wing. A decorative sign beside it read: “We are all faced with a series of great opportunities brilliantly disguised as impossible situations.”

Taglialatela explained that the facility, recently rebranded as the Ape Initiative, draws some funding from behavioral and cognitive research performed by outside scientists. One element of Taglialatela’s own research explores whether Kanzi, trained in the lexigrams, can act as a Rosetta stone, helping researchers decode the vocalizations of bonobos in the wild. “We present him with a task where we play him a sound—a prerecorded bonobo vocalization—to see if he’ll label it with a lexigram,” Taglialatela explained. “When we play him an ‘alarm’ vocalization, we give him three lexigrams to choose from—one being ‘scare,’ and two other random items—to see if he can tell us what kind of information is encoded in the calls of other bonobos.” So far, he said, the results are promising.

He pointed at a lexigram keyboard nailed to the wall of the greenhouse. “The bonobos have constant access to permanently mounted lexigram keyboards in virtually all of their enclosures,” he said. Rather than study the “Pan/Homo” cultural implications of the bonobos’ lexigram use, Taglialatela keeps the keyboards available to enable the apes to request food and activities that fall within the bounds of what he describes as species-appropriate behaviors. He said that the quality of the care the apes receive has improved since he came on board. Kanzi, once overweight, has lost 75 pounds, for example, and since 2014 the staff has worn masks and gloves when interacting with the apes to reduce the risk of transmitting infections.

Kanzi and the other bonobos were outside, rooting around in a tube the staff had installed to mimic a termite mound. Taglialatela left to confiscate the tube to encourage them to join us. While he was gone, I pulled a chair up to the transparent wall of the testing room.

Through the greenhouse was the lake, darkened by rain. Just beyond it was the length of road where one of Taglialatela’s graduate students told me she used to see Savage-Rumbaugh’s red pickup truck during the summer after the trial. She would drive the truck a little way down the road and park, and then climb on top of it. From the building, the staff could just make out her binoculars, the shock of white hair.

Suddenly Kanzi charged into the testing room. I recognized him from videos and news features, but he was older now—balding at the crown, more lean. If he noticed me, he didn’t let on. He hoisted himself up onto the ledge.

Taglialatela handed me a laminated keyboard containing 133 lexigrams, including symbols for “Kanzi,” “Sue,” “Jared,” “keyboard,” and “hurt.” I pressed it up against the glass.

Kanzi had his back to me. From an adjoining room, a staff member was engaging him in a match-to-sample task to demonstrate his vocabulary, speaking a word and waiting to see if he would touch the corresponding symbol on the computer screen. Each time he did, a major chord echoed through the lobby.

Kanzi finished the task—performed, I realized, for my benefit. The screen went blank. As he climbed down from the ledge, his gaze flickered across mine.

Heart pounding, I called out, “Hi Kanzi.” I held up the lexigrams and touched the symbol for “keyboard.”

Kanzi turned away from me and knuckled into the greenhouse, but not before pausing to punch the glass in front of my face.

My cheeks burned. What had I expected? That Kanzi would say something to vindicate either Taglialatela or Savage-Rumbaugh? That, by speaking with me, he would solve the mystery of how “human” he was?

I didn’t feel very human at all in that instant. A wave of queasiness came over me. Kanzi had been going about his life, and my hunger to interact with him had disrupted that. He had no reason to “talk” to me.

The new bonobo, Clara, darted into the greenhouse, and she and Kanzi played for a while. Then Kanzi gestured to Taglialatela, walked on two legs to the keyboard nailed to the wall of the greenhouse, and touched the symbol for “chase.” Taglialatela obliged, pantomiming to him through the glass.

“A lot of people looked at what Dr. Savage-Rumbaugh was doing with Kanzi and say, Oh my god, it’s terrible to think she can’t be here every day,” Taglialatela said. “And I’m like, when we got here, she had been gone for seven or eight months. And a lot of the things that were done with Kanzi, in my opinion, were not appropriate. I mean, they’re bonobos, and they were not being treated as such. I’m not trying to denigrate them. I’m trying to elevate them. This is an animal welfare mission in my mind.”

* * *

One afternoon last summer, I drove to Savage-Rumbaugh’s cabin in Missouri—a one-story structure perched on the edge of a lake and shaded by hickory trees.

Savage-Rumbaugh appeared at the door in a denim button-down shirt and pink jeans, her socked feet tucked into slippers. She led me into the makeshift office she’d set up in the center of the house. In lieu of walls, she had dragged a bookcase between her desk and the stone fireplace that opened out into the living room. The shelves were overflowing. “It was in this house that I decided to go back to school and make a career of psychology,” she said. “I have a clear memory of standing in front of that fireplace and thinking that if I could just publish one article in my lifetime, it would be worth the effort and the money and that I would have made a contribution to science and not let my mind go to waste.”

She was not feeling hopeful these days, she said. Energized by a conference at MIT where she’d presented on interspecies communication, she had recently sent a proposal to collaborate with Taglialatela, but he hadn’t accepted it. She hadn’t seen the bonobos in five years. Meanwhile, the rainforests in the Congo River Basin that are home to most of the remaining 20,000 wild bonobos are being torched by palm oil companies to clear the ground for plantations. Demand for the product, which is used in half of all packaged food items in American supermarkets, from pizza dough to ramen noodles, is skyrocketing. Bonobos, already threatened by poachers and loggers, are suffocating in the fires.

I glanced at a roll of heavy-duty paper tilted against Savage-Rumbaugh’s desk: a copy of the lexigrams. Following my gaze, she pulled it out and unscrolled it on the shag rug, placing three stone coasters around the edges. The lexigram symbol for “Sue” hovered in the upper left-hand corner: a green keyhole with two squiggles shooting out from either side.

“My mother never understood why I did what I did with apes,” she said. “She thought it was strange. Then something happened in the last few weeks before she passed away. She was having so much trouble understanding me, so I stopped speaking to her. Instead, I started writing and painting to get my messages across. It was like a door opened, and all that I actually was flowed into her understanding, and she smiled. And some heavy load lifted.”

In losing spoken language, and falling back on a nonverbal way of communicating, had Savage-Rumbaugh’s mother become any less human? I was reminded of something Savage-Rumbaugh had once said to me about our species’ signature desire: “Our relationship to nonhuman apes is a complex thing,” she’d said. “We define humanness mostly by what other beings, typically apes, are not. So we’ve always thought apes were not this, not this, not this. We are special. And it’s kind of a need humans have—to feel like we are special.” She went on, “Science has challenged that. With Darwinian theory, this idea that we were special because God created us specially had to be put aside. And so language became, in a way, the replacement for religion. We’re special because we have this ability to speak, and we can create these imagined worlds. So linguists and other scientists put these protective boundaries around language, because we as a species feel this need to be unique. And I’m not opposed to that. I just happened to find out it wasn’t true.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c1/aa/c1aa5998-6f69-4118-8ecc-5f37b6f041dd/bonobo_opene_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bf/70/bf705b24-38e0-4861-b06b-bea3f57f4700/opener_kanzi.jpg)