A Book’s Vocabulary Is Different If It Was Written During Hard Economic Times

Books published just after recessions have higher levels of literary misery, a new study finds

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ec/d0/ecd06532-1d64-4965-b19e-2c67ef80932c/books.jpg)

If, in the distant future, archaeologists find no trace of evidence of our civilization apart from a library of 20th century novels, they might be able to figure out something surprising about recent history: the boom times and recessions of our economic system.

A study by a team of British researchers published yesterday in the journal PLOS ONE found a strong correlation between what they call a book's "literary misery index" (the frequency of words such as "anger," disgust," "fear," and "sadness") and the economic misery index (a measure of unemployement and inflation) of either the U.S. or Britain for the ten years that preceded its publication.

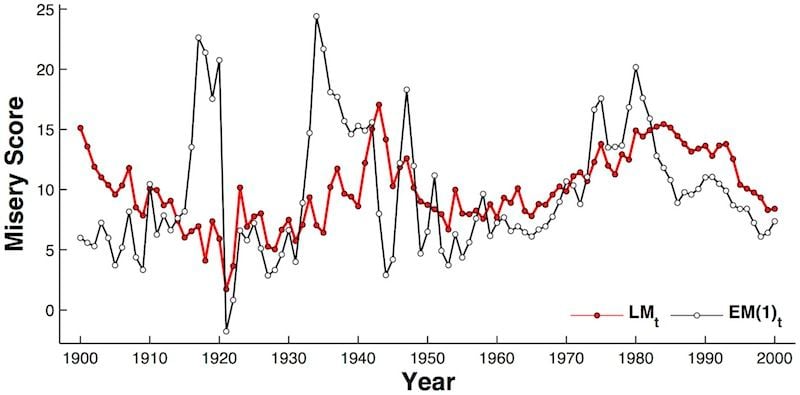

The graph of the average amount of misery in English-language books over the course of the 20th century, in other words, closely tracked the peaks and valleys in the number of Americans and Brits out of work. "It looked like Western economic history, but just shifted forward by a decade,"said Alex Bentley, lead author of the study and an anthropologist University of Bristol, in a press statement.

The researchers created the graph of literary misery by examining the frequency of words of roughly five million digitized books published in English during the 20th century in the U.S., Britain and other parts of the world. Available via Google's Ngram Viewer, the variety and distribution of every word used in these books was already catalogued, so the researchers simply had to run an algorithm that compared the frequency of sad words with that of happy ones.

Their analysis showed that, in the U.S., literary misery peaked in the early 1940s, just after the Great Depression. It dipped during the 50s, following the economic boom driven by the country's entry into World War II, and then slowly rose again during the 70s and 80s, after years of economic stagnation, rising unemployment and relatively high inflation rates.

There are a few possible reasons for the ten-year lag. The most obvious is that writing books takes time—for most authors, years—so a book begun in the depths of the Great Depression of the 1930s might not be published until the next decade.

Alternately, it's possible that the lag is a quirk of the way literature is shaped by authors' childhood experiences. "Perhaps this 'decade effect' reflects the gap between childhood when strong memories are formed, and early adulthood, when authors may begin writing books," Bentley said. "Consider for example, the dramatic increase of literary misery in the 1980s, which follows the 'stagflation' of the 1970s. Children from this generation who became authors would have begun writing in the 1980s.

To check whether the correlation between literary and economic misery in the English canon was a coincidence, the researchers also performed the same analysis on a catalogue of some 650,000 German books. When compared to German economic conditions, they found the same trend.

Of course, this correlation, whether in the U.S., Great Britain or Germany, might not come as a huge shock—obviously, the circumstances that surround an author influence his or her word choices. But the fact that the signal of economic times could be consistently spotted through the noise of all of an author's personal circumstances is still somewhat surprising, and shows what a profound effect economics have on our creative mindsets. As Bentley put it, "global economics is part of the shared emotional experience of the 20th century."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)