Bringing Extinct Birds Back to Life, One Cartoon at a Time

In his new book, Extinct Boids, artist Ralph Steadman introduces readers to a flock of birds that no longer live in the wild

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130102105010Double-banded-Argus-web.jpg)

Filmmaker Ceri Levy was working on a documentary called The Bird Effect, about how our feathered friends influence our lives, when he took on a side project, organizing an exhibition, “Ghosts of Gone Birds,” at the Rochelle School in London in November 2011.

“Its purpose was to highlight the risk of extinction that is faced by many bird species in the world today,” Levy noted. “The premise of the show was to get artists to represent an extinct species of birds, and to breathe life back into it.”

Levy sent a list of nearly 200 extinct bird species to famous artists, musicians, writers and poets, inviting them to create bird-centric pieces. A cut of the profits from the sale of the artwork would go to BirdLife International’s Preventing Extinctions Programme, which aims to protect 197 critically endangered bird species.

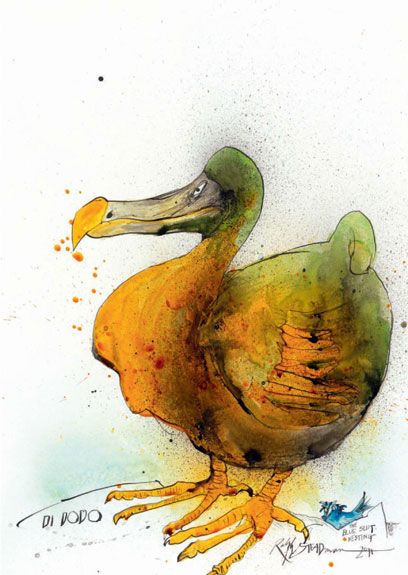

Acclaimed poet and novelist (also, environmental activist) Margaret Atwood knitted a Great auk—a large flightless seabird last seen off of Newfoundland in 1852. Sir Peter Blake, a British pop artist who famously designed the cover of the Beatles’ album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, submitted a collage, titled “Dead as a Dodo,” which consists of a long list of extinct and endangered birds. But the most prolific contributor by far was Ralph Steadman. The British cartoonist, who illustrated the 1967 edition of Alice in Wonderland and Hunter S. Thompson’s 1971 classic Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (and the labels on bottles of Flying Dog beer), painted more than 100 colorful and sometimes silly birds—or “boids,” as he called them in emails to Levy.

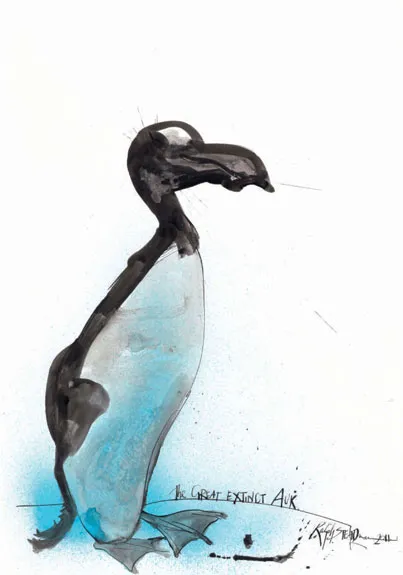

Steadman started by creating a beautiful Japanese egret in flight. Then, he painted a great auk and a rather plump North Island giant moa. A relative of the ostrich, the moa lived in New Zealand until hunting and habitat loss led to its disappearance by the 1640s. He quickly followed those up with a Choiseul crested pigeon. A regal-looking thing, the pigeon flaunts a big blue crest of feathers, like a fashionable headpiece; it was found in the Solomon Islands until the early 1900s, when it went extinct, quite dreadfully, on account of “predation by dogs and cats,” writes Levy.

At this point, the artist emailed Levy: “I may do a few more—they are rather fun to do!”

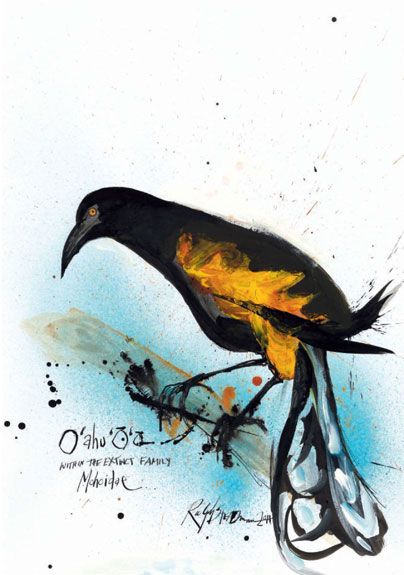

Steadman proceeded to paint a black mamo, a Jamaican red macaw, a Chatham rail and an imperial woodpecker. He added a red-moustached fruit dove, a Carolina parakeet, a Labrador duck, a white-winged sandpiper, a Canary Islands oystercatcher and a passenger pigeon to the mix, among others, all featured in his and Levy’s new book on the series, Extinct Boids.

Calling Steadman’s birds “boids” seems fitting, according to Levy. ”These are not scientific, textbook illustrations. These are Ralph’s take on the subject,” the filmmaker and curator writes. “He has stamped his persona upon them, and given them their own unique identities.” The cartoonist’s Mauritius owl looks dim-witted, and his Rodrigues solitaire is quite perturbed. His snail-eating coua is perched on the shell of its alarmed prey, almost as if it is gloating. And, his New Zealand little bittern is, how shall I say it…bitter.

“I was thinking that what is desirable is to get the spirit and personality of the BOID!!! Rather than some odd ‘accuracy’!!” Steadman wrote to Levy, in the process of painting the aviary. As a result, his ink-splattered portraits are downright playful.

Each one has a story, especially this drowsy-looking boid (above) called the double-banded argus. The focal point of the illustration is a speckled orange feather—the “only original feather,” as Steadman scrawls in the caption. In the book, Levy provides the backstory. Apparently, one feather, resembling the plumage of an argus pheasant but with a distinctly different pattern, exists to this day, leaving some to believe that a double-banded argus once lived. With just the feather to guide him, Steadman dreamed the bird into being.

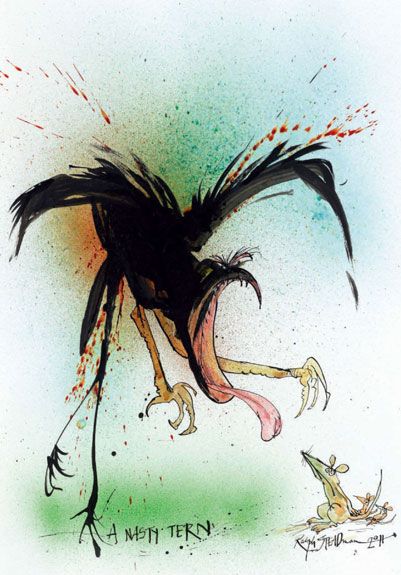

In fact, in addition to depicting numerous known species, the artist imagined a flock of fantastical, cleverly-named characters: the gob swallow, the nasty tern (“nasty by name and nasty by nature,” says Levy) and the white-winged gonner, to name a few.

Included in this wily bunch is Carcerem boidus, otherwise known as the jail bird.

“There’s always got to be one bad egg, and this is what came out of it,” says Levy, in response to the caged, black-and-white striped bird he imagined.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)