Paleoartist Brings Human Evolution to Life

For Elisabeth Daynès, sculpting ancient humans and their ancestors is both an art and a science

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e8/5b/e85bd6ec-f4fd-420a-8cbe-903a0e309e58/0039201edit.jpg)

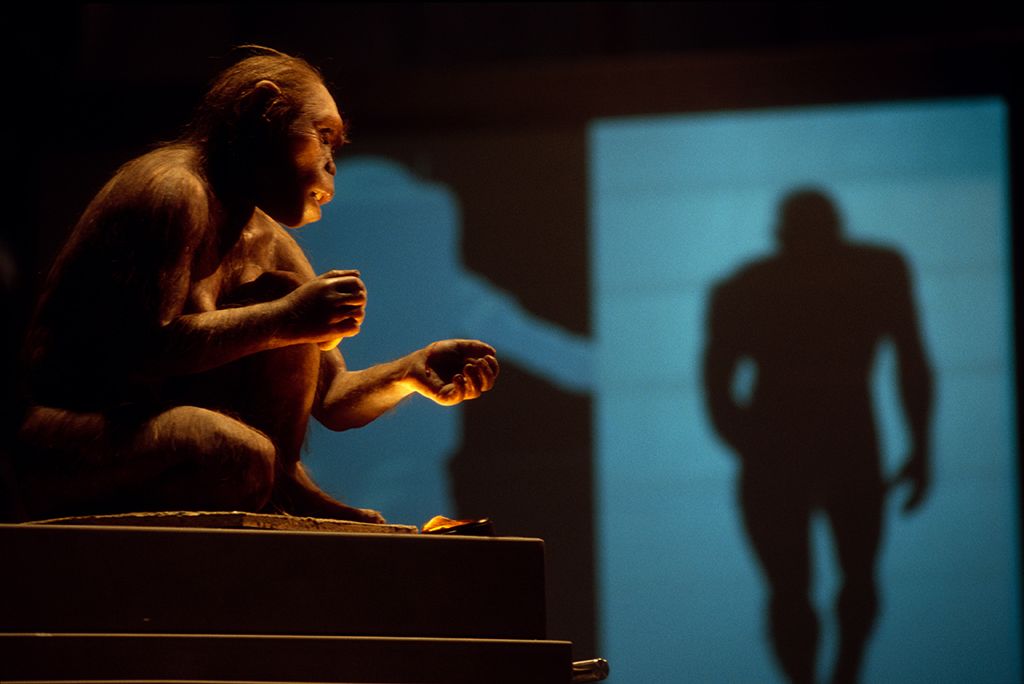

A smiling 3.2-million-year-old face greets visitors to the anthropology hall of the National Museum of Anthropology and History in Mexico City. This reconstruction of the famous Australopithecus afarensis specimen dubbed “Lucy” stands a mere 4 feet tall, is covered in dark hair, and displays a pleasant gaze.

She’s no ordinary mannequin: Her skin looks like it could get goose bumps, and her frozen pose and expression make you wonder if she’ll start walking and talking at any moment.

This hyper-realistic depiction of Lucy comes from the Atelier Daynès studio in Paris, home of French sculptor and painter Elisabeth Daynès. Her 20-year career is a study in human evolution—in addition to Lucy, she’s recreated Sahelanthropus tchadensis, as well as Paranthropus boisei, Homo erectus, and Homo floresiensis, just to name a few. Her works appear in museums across the globe, and in 2010, Daynès won the prestigious J. Lanzendorf PaleoArt Prize for her reconstructions.

Though she got her start in the make-up department of a theater company, Daynès had an early interest in depicting realistic facial anatomy and skin in theatrical masks. When she opened her Paris studio, she began developing relationships with scientific labs. This interest put her on the radar of the Thot Museum in Montignac, France, and in 1988, they tapped Daynès to reconstruct a mammoth and a group of people from the Magdalenian culture who lived around 11,000 years ago.

Through this initial project, Daynès found her calling. “I knew it straight away after [my] first contact with this field, when I understood how infinite [scientific] research and creativity could be,” she says.

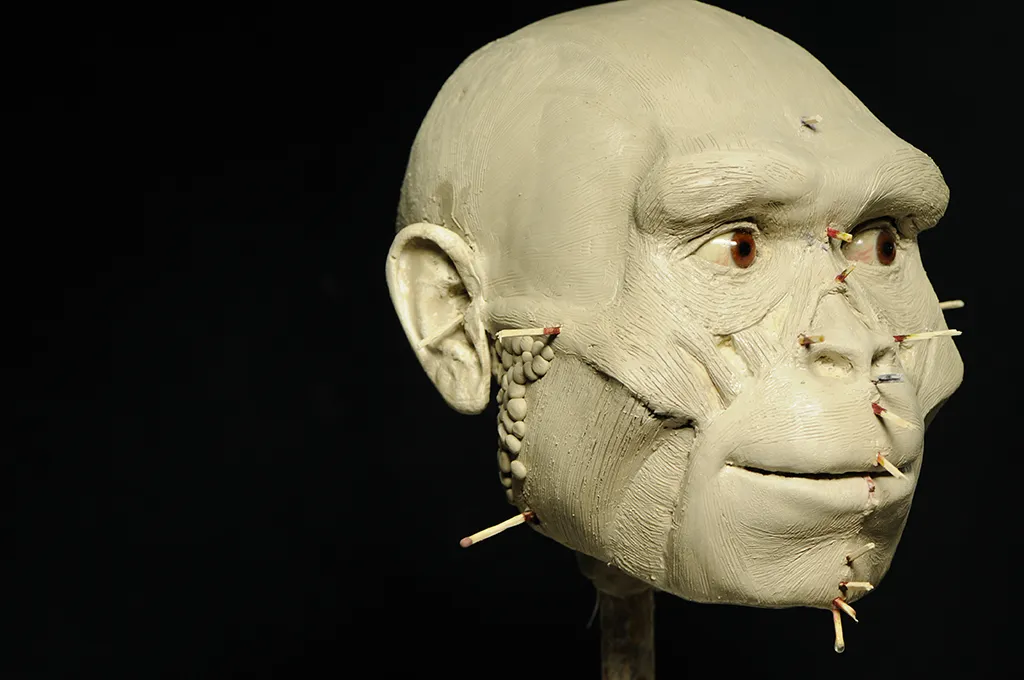

Although her sculpting techniques continue to evolve, she still follows the same basic steps. No matter the reconstruction, Daynès always starts with a close examination of the ancient human’s skull—a defining feature for many hominid fossil groups.

Computer modeling of 18 craniometric data points across a skull specimen gives her estimates of musculature and the shape of the nose, chin, and forehead. These points guide Daynès as she molds clay to form muscles, skin and facial features across a cast of the skull. Additional bones and teeth provide more clues to body shape and stature.

Next, Daynès makes a silicone cast of the sculpture, a skin-like canvas on which she’ll paint complexion, beauty spots and veins. For hair, she typically uses human hair in members of the Homo genus, mixing in yak hair for a thicker effect in older hominids. Dental and eye prosthetics complete the sculpture’s form.

For hair and eye color decisions, Daynès gets inspiration from the scientific literature: for example, genetic evidence suggests that Neanderthals had red hair. She also consults with scientific experts on the fossil group at each stage of the reconstruction process.

Her first collaboration with a scientist on a reconstruction came in 1998 when she teamed up with longtime friend Jean-Nöel Vignal, a paleoanthropologist and former head of the Police Forensic Research Institute in Paris, to reconstruct a Neanderthal from France’s La Ferrassie cave site. Vignal had developed the computer modeling programs used to estimate muscle and skin thickness.

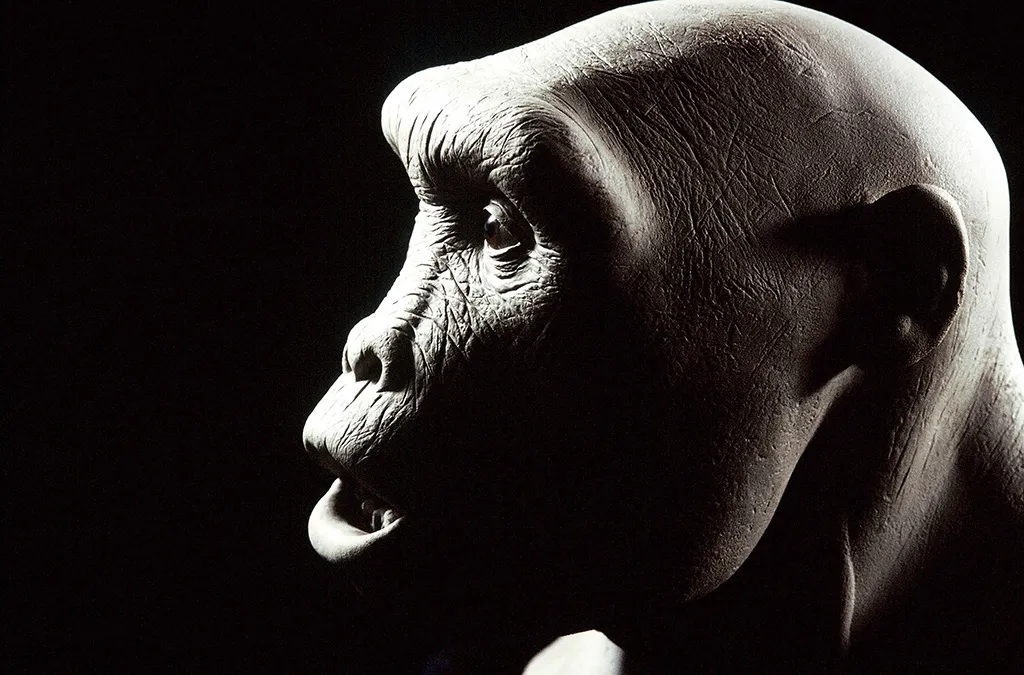

Forensic sleuthing, she says, is the perfect guide: She approaches a reconstruction like a investigator profiling a murder victim. The skull, other bone remains and flora and fauna found in the excavation all help develop a picture of the individual: her age, what she ate, what hominid group she belonged to, any medical conditions she may have suffered from, and where and when she lived. More complete remains yield more accurate reconstructions. “Lucy” proved an exceptionally difficult reconstruction, spanning eight months.

Daynès synthesizes all of the scientific data about that point in hominid evolution into one sculpture, presenting a hypothesis of what the individual looked like. But the full reconstruction “is both an artistic and scientific challenge,” she says. “Reaching an emotional impact and transmitting life requires important artistic work unlike a conventional reconstruction that would be realized in a forensic laboratory,” explains Daynès.

There’s no scientific method to predict what anger or wonder or love might have looked like on the face of Homo erectus, for example. So for facial expressions, Daynès goes with artistic intuition, based on the hominid family, exhibition design, and any inspiration conjured by the skull itself.

She also turns to the expressions of modern humans: “I cut out different looks from recent photos in magazines that hit me and that I think can apply to a specific individual.” For example, Daynès modeled a Neanderthal man looking powerlessly at his companion, wounded in a hunting accident, for the CosmoCaixa Museum of Barcelona, on a Life magazine photo of two American soldiers in Vietnam.

Through these expressions and the realistic feel of the sculptures, Daynès also tries to dispel stereotypes of ancient hominids being violent, brutish, stupid, or inhuman. “I am proud to know that they will shake up common preconceptions,” Daynès says. “When this happens, the satisfaction is great—this is the promise that visitors will wonder about their origins.”

Daynes has several upcoming exhibitions at museums around the world. At the Montreal Science Centre, four of Daynès’ reconstructions of Magdalenian painters is on view through September 2014. In Pori, Finland, the Satakunta Museum features Daynès’ reconstructions of Neanderthals in an exhibition focused on the world they inhabited. Two additional exhibitions will launch later this year in Bordeaux, France, and in Chile.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)