Building to a Different Drummer

Today’s timber frame revivalists are putting up everything from millionaire mansions to a replica of Thoreau’s cabin

Dressed in a canvas kilt, Ben Brungraber looks like what Henry David Thoreau might have had in mind when he wrote of a man marching to the beat of a different drummer. Brungraber is the senior engineer and resident eccentric at Bensonwood, a company employing practitioners of timber framing, an age-old technique of building with heavy timbers—beams and posts and braces—fastened together with precisely cut, interlocking mortise and tenon joints and big wooden pegs. He and 35 other volunteers, mostly Bensonwood employees, are building a replica of Thoreau's cabin, a timber frame structure, for the Thoreau Institute at Walden Woods, near Concord, Massachusetts.

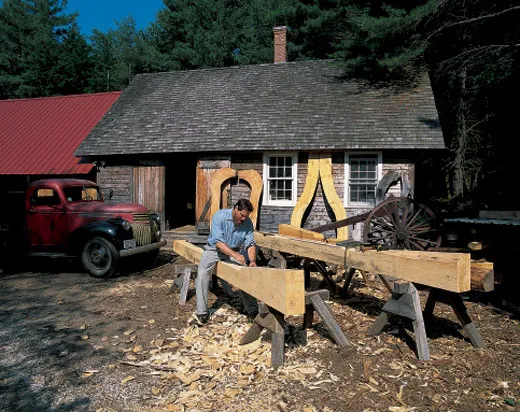

Timber frame revivalists range from high-tech to hands-on. At Bensonwood, a massive $400,000 German-made, automated timber-cutting tool dubbed "Das Machine" could have cut all the joinery for Thoreau's cabin in minutes with strokes of a few computer keys. At the other end of the spectrum are traditional purists like Jack Sobon, who uses only hand tools and hauls logs out of the forest using oxen.

Mortise and tenon joints have been found in 3,000-year-old Egyptian furniture and in ancient Chinese buildings. Part of a temple in Japan, rebuilt using timber framing techniques, is the world's oldest surviving wooden structure. By the tenth century A.D., cathedrals with complex timber frame roof systems were going up across Europe. Immigrants brought timber framing methods to the New World, but in the mid-1800s, timber framing in the United States began to wane. High-production sawmills made standardized lumber widely available, and railroads transported huge loads of 2 x 4s used in stud framing. But the aesthetics of the bright, open spaces of timber frame structures, a stark contrast to the humdrum, boxy look of many conventionally framed houses, have inspired a timber frame renaissance.