Can the Siberian Tiger Make a Comeback?

In Russia’s Far East, an orphaned female tiger is the test case in an experimental effort to save one of the most endangered animals on earth

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7a/8f/7a8f68e2-ecb7-4769-ae6c-041b404ca8aa/feb15_d01_tigers.jpg)

From its origins in Russia’s remote Primorsky Province, the Krounovka River wends northeast, passing through ridges red with willow trees and barren stretches of grassland, before finally joining a larger river known as the Razdolnaya. By modern standards, the river valley is all but unpopulated, save the odd logging outpost, but in the winter months the region fills with amateur sportsmen who come to stalk the abundant sika deer and the freshwater trout.

On a frigid afternoon in February 2012, a pair of hunters working the Krounovka were halted by an unusual sight: a 4-month-old Amur tiger cub, lying on her side in a drift of snow. A typical Amur, hearing the sound of human footsteps, will either roar in an attempt to scare off the interlopers or melt away entirely. This cat was different. Her eyes were glazed and distant, her breathing shallow. The hunters tossed a blanket over her head and carted her into a nearby town, to the home of Andrey Oryol, a local wildlife inspector.

Oryol immediately recognized the severity of the situation. The cat, who was eventually given the name Zolushka—Cinderella, in English—had clearly not eaten in days, and the tip of her tail was black with frostbite. Oryol made an enclosure for her in his wood-lined banya, or steam bath, and fed her a steady diet of meat, eggs and warm milk. After a few days, her vitals had stabilized; after two weeks, she was back up on all four paws, pacing restlessly. Heartened, Oryol reached out to Dale Miquelle, an American scientist based in Primorsky, and asked him to come at once.

“My first thought was that the mother had probably been poached, and that the poachers couldn’t find or had no use for the cubs,” Miquelle recalled recently. “Mothers are a lot more vulnerable to poaching than other tigers, because they’ll try to stand their ground—a mother doesn’t want to abandon her cubs, and she might not have time to get them together to escape. So she ends up getting shot.”

Among tiger specialists, a close-knit group, Miquelle, the director of the Russia Program of the Wildlife Conservation Society, an American nonprofit, is a gruff, laconic presence—an action man and not a classroom man, who, by his own admission, is much better suited to fieldwork than to interpersonal politics. There are only a few scientists alive with his skill for tracking and catching live tigers, and when a big cat is found anywhere in Russia’s Far East, Miquelle and his team are usually the first summoned to lend a hand.

Miquelle arrived at Oryol’s house shortly after lunch, along with Sasha Rybin, a WCS colleague. Oryol showed them into the banya. Immediately, Zolushka began to snarl. Adolescent tigers, despite their relatively small stature—Zolushka was about the size of a golden retriever—are dangerous animals, with sharp claws and teeth and a frightening growl that’s almost like an adult’s. “It can really knock you back,” Miquelle told me. He used a stick to distract her while Rybin jabbed her with a dart containing Zoletil, a tranquilizer. Once she had collapsed, they lifted her out of her enclosure and placed her on a nearby table, where a pair of local veterinarians performed surgery to amputate the necrotic tip of her tail. Bandaged and sedated, Zolushka was moved to the Center for the Rehabilitation and Reintroduction of Tigers and other Rare Animals, 50 miles to the south in Alekseevka.

Opened months earlier by a coalition that included the Russian Geographical Society and the government-funded group Inspection Tiger, the Alekseevka Center spilled over eight acres thick with brush and vegetation. There was sheeting on all the fences, so that captive tigers wouldn’t be able to see outside, and a series of chutes so that prey could be introduced surreptitiously, a system designed in consultation with Patrick Thomas, an expert from the Bronx Zoo. Meanwhile, a battery of cameras allowed scientists to observe the animals from a control center without disturbing them. “There were two main goals,” Miquelle recalled. “Don’t let the animal get acclimated to humans. And teach her to hunt.”

The practice of rehabilitating wild predators to prepare them for release back into the wild is not unheard of. It has been accomplished successfully, for example, with bears, the lynx in North America and, once, in India with Bengal tigers. But it is new enough to remain controversial, and for WCS and the other organizations involved with the Alekseevka Center, the release of Amur tigers represented a tremendous risk. A few years earlier, a wild cat that had been captured and collared by WCS staff killed a fisherman outside the coastal community of Terney, in Primorsky; Miquelle, who lives in the village, told me that the incident turned the town against him and his employees. If one of the rehabilitated cubs became a so-called “conflict tiger,” Miquelle told me, “it could easily set back tiger conservation in the region a hundred years.”

But the upsides of reintroduction were enormous: If left-for-dead orphaned cubs could be rehabilitated to the point of mating with wild tigers, they would not only provide a boost in the local population but, in the aggregate, perhaps reclaim regions that hadn’t seen healthy tiger communities in decades. Beyond that, the hope was to establish a model that scientists in other countries could perhaps one day duplicate.

Zolushka was the first tiger to arrive at Alekseevka—the test case. In the early months, she was fed primarily meat, dumped into the enclosure through one of the slots in the fencing. In the summer of 2012, a pair of young scientists from Moscow, Petr Sonin and Katerina Blidchenko, traveled to Vladivostok to help inaugurate the next phase in Zolushka’s rehabilitation. Sonin and Blidchenko presented Zolushka initially with rabbits—fast, but ultimately defenseless. The next step was wild boar, a thickset animal with formidable tusks and the low-slung center of gravity of a tank. The boar seemed at first to confuse Zolushka. She could catch up to it easily enough, but the kill itself was harder to accomplish. A rabbit was downed with a single snap of the jaws; a boar fought back. “It was like a kid trying to figure out a puzzle,” says Miquelle, who was a periodic visitor to the center in those weeks. “She got it, but it took a little time.”

Three boars in, and Zolushka was driving the animals to the ground with grace and skill. She did the same with much larger sika deer, which were pushed through a chute and into the enclosure. She was healthy, she was growing fast, and she could kill as ably as many wild tigers.

In May 2013, a little more than a year after she arrived at the Alekseevka Center, the decision was made: It was time for Zolushka to be set free.

***

The Amur tiger—also known as the Siberian—is, along with the Bengal, the biggest in the tiger family. Amurs are ocher and russet, with a pink nose, amber eyes and thick black stripes that band their bodies in patterns as unique as any fingerprint. An adult male Amur can measure as long as 11 feet and weigh 450 pounds; the average female is closer to 260. On the kill, an Amur will load its powerful back haunches and slam forward like the hammer of a revolver. To watch a tiger bring down a deer is to see its weight and bulk vanish.

The Amur probably traces its lineage to an ur-species of Panthera tigris, which enters the fossil record about two million years ago. Over the ensuing millennia, nine distinct subspecies of tigers emerged, including the Bengal and the Amur. Each was an apex predator—the pinnacle of its region’s food chain. Unlike the bear, a formidable predator who feasts on both flora and fauna, the tiger is purely carnivorous, with a preference for ungulates such as deer and wild pigs; it will starve before consuming a plant.

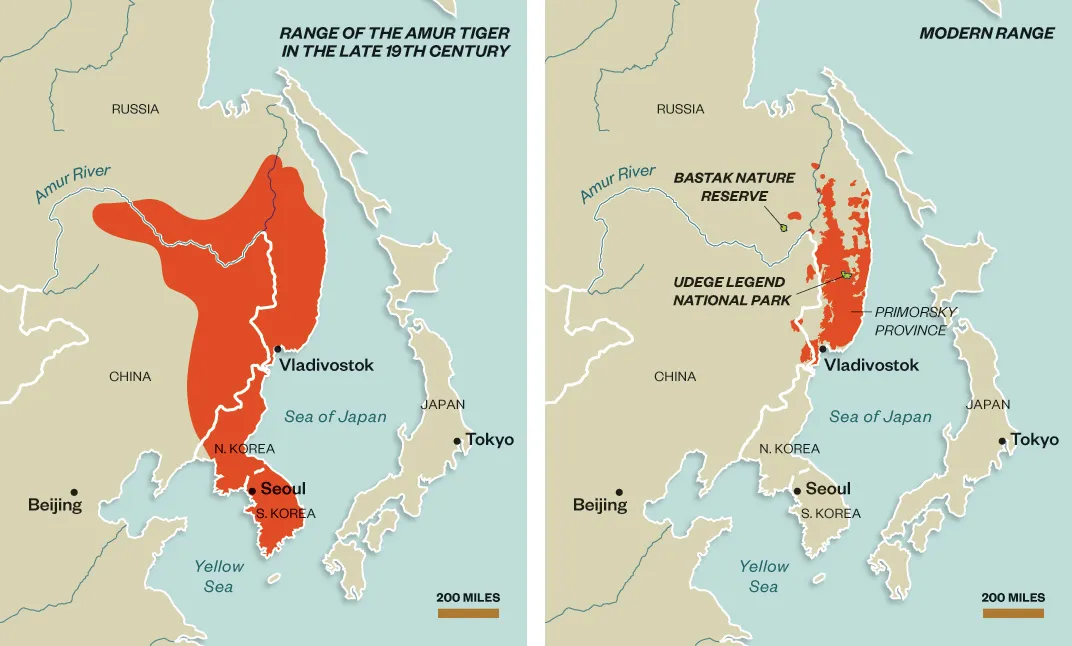

In the not-so-distant past, tigers roamed the shorelines of Bali, the jungles of Indonesia and the lowlands of China. But deforestation, poaching and the ever-widening footprint of man have all taken their toll, and today it is estimated that 93 percent of the ranges once occupied by tigers have been eradicated. There are few wild tigers remaining in China and none in Bali, nor in Korea, where medieval portraits showed a sinuous creature with a noble bearing and a nakedly hungry, open-mouthed leer—an indication of the mixture of dread and admiration humans have long felt for the beast. At the turn of the 20th century, it was estimated that there were 100,000 tigers roaming the wild. Now, according to the World Wildlife Fund, the number is probably much closer to 3,200.

In a way, the area comprised of Primorsky and neighboring Khabarovsk Province can be said to be the tiger’s last fully wild range. As opposed to India, where tiger preserves are hemmed in on all sides by the thrum of civilization, the Far East is empty and conspicuously frontier-like—a bastion of hunters, loggers, fishermen and miners. Just two million people live in Primorsky Province, on a landmass of nearly 64,000 square miles (about the size of Wisconsin), and much of the population is centered in and around Vladivostok—literally “the ruler of the east”—a grim port city that serves as the eastern terminus of the Trans-Siberian Railway and the home base of WCS Russia.

This past autumn, I flew to Vladivostok to meet with Dale Miquelle, who had agreed to show me around his ward, which extends from the southern lip of Primorsky to the easternmost reaches of Siberia, where the mixed coniferous and deciduous forest, the natural habitat of the Amur, comes to an end. (“I go as far as tigers go,” Miquelle is fond of saying.)

At 7 on a dark morning in late October, a forest green Toyota HiLux squealed to a stop in front of my hotel, and Miquelle piled out. As animals go, Miquelle is more bear than tiger—broad-shouldered, shambling, with meaty paws and unruly black-and-white hair. Now 60, Miquelle was raised outside of Boston and studied at Yale (he was originally an English major), before moving on to the University of Minnesota for his master’s degree and the University of Idaho, where he received his doctorate in biology in 1985. His specialty was moose. In 1992, shortly after the Soviet Union was dissolved, Miquelle was part of a small delegation of Americans dispatched to the Far East to work with Russian scientists to study the habitats of the dwindling Amur population. The other Americans went home several months later; Miquelle has never left.

Miquelle describes his work at WCS Russia as both research and conservation—“with the research making the conservation possible,” he says. He oversees what is generally agreed to be the longest-running field research project on the Amur in history. Using GPS collars and other tracking techniques, he has established an unrivaled library of data on his subject, from the size of the territory a male Amur might mark for his own (averaging nearly 500 square miles) to its preferred prey (red deer and wild boar top the list). That information has allowed Miquelle to advise the government on what areas need to be better protected, and to help establish new reserves in Russia and China. “The effectiveness of conservation grows proportionally in relation to how much you know about the animal,” Miquelle told me. “You can’t go at it blind, you know?”

That morning he had an itinerary ready for me: a ten-hour drive north to an old mining village called Roshchino, where we would catch a ferry across the Iman River and drive another hour to Udege Legend National Park. There we would trek up into the hills to set up camera traps, invaluable tools for monitoring wild animals: Placed correctly, the combined infrared and photographic lenses stir to life at the first sign of motion or heat and provide imagery and data that might otherwise take months of backbreaking work to obtain. A few cats had been seen in Udege Legend, Miquelle told me, and he wanted to get a grip on their numbers.

At the outskirts of Vladivostok, crumbling old housing complexes gave way to tall copses of Korean pine, and soon we were barreling across the surface of a great, gray plain. To pass the time, Miquelle talked to me about history. In the 1940s, he explained, it was believed that there were as few as 20 Amur tigers left in the Far East. But communism, which had been ruinous for many Russian people, was actually good for Russia’s big cats. During the Soviet era, the borders were tightened, and it became difficult for poachers to get the animals into China, the primary market for tiger pelts and parts. After the Soviet Union collapsed, the borders opened again, and perhaps more calamitously, inflation set in. “You had families whose entire savings was now worth zilch,” said Miquelle, whose wife, Marina, is a native of Primorsky. “People had to rely on their resources, and here, tigers were one of the resources. There was a massive spike in tiger poaching.”

By the mid-1990s, it seemed possible that the Amur tiger would soon be extinct. Back then, Miquelle worked for the Hornocker Wildlife Institute, an organization founded by the scientist Maurice Hornocker that later merged with the WCS. Although Russian field men had already done good work counting and studying the remaining population of Amur tigers, they were limited to working in the winter, when tiger prints were visible in the snow. The Hornocker Wildlife Institute brought radio collars, transmitters and the telemetry experience necessary to track big cats remotely.

It was a depressing time: Almost every tiger the group collared seemed to be poached. Sometimes the poachers would cut the collar off the animal with a hunting knife; sometimes they’d blast it with a rifle, to halt the transmission of the radio signal. A 1996 census of the Far East’s Amur population, using traditional snow-tracking methods and the expertise of area hunters and rangers, concluded that there were somewhere between 330 and 371 tigers in the region, and maybe 100 cubs. In 2005, Miquelle and his team led a second census, which put the count at between 331 and 393 adults and 97 to 109 cubs. Miquelle believes the numbers may have dipped slightly in the few years afterwards, but he is confident that heightened conservation efforts, a more energetic defense of protected lands and improved law enforcement have now stabilized the population. A census planned for this winter should help clarify the numbers.

But stabilization is different from growth, which is what makes the Zolushka experiment so intriguing. For conservationists in Russia, it is not just the cauterizing of a wound but a way forward—the nursing back to healthy life of a sick body.

***

Near Vladivostok, the air had been clear and mild, but as we made our way north the temperatures dropped and the skies filled with snow. Logging trucks and military convoys shuddered past us, their loads lashed down with heavy black cord.

We reached Roshchino around 5, in the midst of what was shaping up to be a full-blown storm. The streets were dark and silent, the trees stooped with snow. The Udege Legend chief inspector was waiting for us at his office. Miquelle, who speaks Russian fluently, if unadroitly, with a heavy American accent, announced plans to proceed immediately to the park. Impossible, the inspector said: The weather was too bad. But if we wanted, we could stay with the local accountant, who had two spare beds in his office.

“Turn-down service is at 6,” Miquelle deadpanned, in English. “And I hear the tapas restaurant upstairs is superb.”

That night, over a bottle of flavored vodka, Miquelle booted up Google Earth on his laptop and traced his finger across the screen. Beginning in late 2012, five new orphaned cubs were brought to the Alekseevka Center for rehabilitation: three males and two females. Last spring, they were outfitted with GPS collars and reintroduced into the wild. One of the tigers, Kuzya—known as “Putin’s tiger,” because the Russian president was said to have personally sprung the cat from his enclosure—has become famous for swimming across the Amur River into China, where, according to Chinese state media, he gobbled five chickens out of a rural henhouse. The colored lines on the Google Earth display represented the tracks of the five orphans.

Two of the male cats proved to be wanderers, ranging hundreds of miles from their drop site across mountain ridges and soggy marshland. The third male and the females staked out an area and remained near it, making shorter trips within the taiga to hunt for prey. Miquelle brought up a second map, which displayed data from the collar worn by Zolushka.

In the weeks leading up to her release, the team at the center had considered a range of options for the reintroduction site, but settled on Bastak Zapovednik, in Russia’s remote Jewish Autonomous Region, some 300 miles to the north. “The thinking was that Bastak had plenty of boar and red deer,” Miquelle told me. “But most importantly, this was an area where there were once tigers, and now there weren’t. It was an opportunity to actually recolonize tiger habitat. That’s totally unheard of.”

Removing Zolushka from the Alekseevka Center turned out to be much more difficult than getting her in. As a cub, she’d been drugged and carried through the gates; now, as an adult, she had grown comfortable with her surroundings, and at the sound of humans approaching, she’d wade toward the middle of the pen and flatten herself in the undergrowth. It would have been suicidal for the WCS staff to chase after her on foot, so Sasha Rybin, the same fieldworker who had tranquilized Zolushka a year earlier, climbed up into an observation tower and shot her with a Zoletil dart.

Zoletil sedates an animal and slows its breathing without halting it altogether, and one of the uncomfortable realities of tranquilizing big predators is that their eyes remain mostly open. Zolushka, now weighing more than 200 pounds, was rolled onto a stretcher and carried to a nearby truck.

Fourteen hours later, the vehicle arrived at the release site. The door on Zolushka’s crate was lifted remotely. She sniffed around uneasily and then, her truncated tail extended, she leapt down and waded into the brush. From his home in Terney, Miquelle watched the GPS data for evidence that Zolushka had passed a vital test: her first kill in the wild. At the Alekseevka Center, her prey had been fenced in as certainly as Zolushka herself; here, it could run for miles, and tigers tire easily. Zolushka would have to be patient and cunning. Otherwise, she’d die.

Five days after her release, Zolushka’s GPS signal went stationary—often an indication that a tiger has brought down prey and is feasting on the carcass. Rangers waited until Zolushka had moved on, and then trekked to the site, where they found the remains of a sizable badger. In the ensuing months Zolushka killed deer and boar; initially, she was disinclined to wander, but soon she was making regular forays far afield, at one point walking a few dozen miles north, to the adjoining province of Khabarovsk.

Then, in August, utter calamity: Zolushka’s GPS collar malfunctioned, leaving no surefire way for scientists to track her remotely. “I was really freaked out,” Miquelle told me. “She’d survived the summer, but winter is critical. A cat has to be able to eat and stay warm.” If it can’t, it will often approach villages to search for easier pickings, like cattle or domestic dogs. Humans are put in danger, and the cat, now a “conflict tiger,” is often killed.

I looked at the screen. The last bit of data from Zolushka’s GPS unit had been registered more than 12 months earlier. After that, there was nothing.

***

In the morning it was still snowing. The fire that heated the accountant’s office had gone out in the night, and we got ready in the cold, pulling waterproof gaiters over our boots. Miquelle favors camouflage in the field, and today he dressed head to toe in olive greens and earthy browns, pulling a black and white wool cap low over his wide forehead. Three miles out on the ferry road and we started to see cars in the undergrowth, the drivers standing helplessly alongside them, staring back at us without emotion. They were stuck, but in Primorsky, help is rarely given to strangers and even more rarely asked for.

Alex, the inspector who had been recruited to get us to Udege Legend, accelerated past them. He tut-tutted under his breath, as if to say, How could you be so stupid to get stuck out here, in the middle of nowhere? The desolation was complete. You saw a hill in the far distance, and you thought to yourself that over that hill, there would be some sign of civilization, something to indicate that human beings inhabit this land, but you crested the hill only to find more emptiness, more of the same trees, more of the same snow.

Battling poaching in the Far East has always been a difficult proposition: People are poor and often desperate, and the sheer size of the area makes law enforcement difficult. WCS has teamed up with other organizations to educate locals about the importance and fragility of the Amur population. But Miquelle remains under no illusions that he will get through to everyone.

“We talk about tragedy in terms of tigers, but you’ve got to think about tragedy in terms of people. Sometimes, poachers are poaching because they’re starving, and they need food for their families.” In the Far East, a dead tiger can go for thousands of dollars. “You’re never going to be able to beat out poaching unless the economy drastically changes,” Miquelle says. “There will always be that temptation.”

Yet there has been progress on cracking down on poaching, including the widespread adoption by parks across the Far East of the SMART-based protocol—a computer program, now in use in dozens of countries, that collects and collates data from patrols and poaching busts and allows managers to better evaluate the effectiveness of their teams. It has helped that the Russian government, under Vladimir Putin, has turned its attention to the plight of the Amur. In 2010 Putin presided over an international tiger summit, in St. Petersburg, where 13 countries pledged to double the world’s tiger population by 2022. And in 2013, the Russian president spearheaded the enactment of a strict anti-

poaching law that raised the penalty for possession of tiger parts from a minor administrative fine to a criminal offense punishable by a lengthy spell in prison.

But as old threats are addressed, new ones arise. Miquelle is particularly concerned about the arrival of canine distemper disease in tigers, a development that scientists still do not fully understand. “With conservation, you win battles, but not the war,” Miquelle told me. “You don’t get to say, ‘I’ve succeeded, time to go home.’ You’re in it for life, and all you can do is do your best, and hand it over to the next generation.”

At the Udege Legend ranger station, we were joined by a squad of inspectors and two WCS team members: David Cockerill, an American volunteer from Maryland, who was spending the winter in Primorsky; and Kolya Rybin, Sasha’s older brother. We piled into two trucks and made our way into the surrounding hills. The Udege Legend staff estimated that there were somewhere close to ten tigers in the area, but they’d never had access to the camera traps that would help confirm their suspicions, so Miquelle had arranged to lend them 20 units and designed a program for the cameras’ use. As we climbed, the road narrowed, and the snow grew deeper, until we were 500 feet over the valley floor. Pressing my hand to the window glass, I found that I could barely make out the Iman River, a shard of metal in the fields below.

We drew to a halt in the shadow of a high ridge. Tigers often frequent the bottom of cliff faces, where there is shelter from the driving winds, and where an animal can leave a scent mark that will hold for weeks. Later, the same cat will circle back to see if another tiger has marked it. It was a good place for a trap, Miquelle said.

A pair of cameras would be set about ten feet apart, the idea being that one would catch the left side of the tiger, and the other the right, to collect as much visual data as possible. With Miquelle directing, the rangers sliced away the undergrowth and Rybin strapped up the cameras. To test the first lens, a ranger named Sasha crouched down and passed in front of the camera. A red light blinked; motion had been detected. The rangers cheered.

We installed two more sets of traps and turned around to head home. The sunset was the most beautiful I have ever seen: purple and indigo and resinous red. The adjacent ridges seemed to be on fire. I’d initially been surprised that the Amur tiger, with its orange pelt, could adequately camouflage itself in the snows of the Far East. Now it didn’t seem so hard to believe. I thought of something that Miquelle had said about the first time he encountered a wild Amur. “I was just struck by this feeling that this animal truly belonged, if that’s the right word. It was perfectly in sync with its surroundings.”

***

In September 2013, a month after Zolushka’s collar had stopped transmitting GPS data, the monitoring team was able to use the collar’s radio signal to roughly pin down her location: She was still within the reserve, somewhere near the Bastak River.

Last winter, Miquelle traveled to Bastak to find out what had happened to her. Working off the radio signal data, he and a pair of Russian scientists were able to find a set of recent tracks, which met at several points with boar prints. Curiously, there was a set of larger prints, too, with distinctive digital pads: another tiger.

Camera trap images soon proved what Miquelle and others had previously dared only to hope: The second tiger was a healthy male. One evening, Miquelle invited me to his house in Terney to look at some of the images. When he first moved into the village, Miquelle’s neighbor was a woman named Marina. A cantankerous goat that Miquelle had been saving to serve as tiger bait ate Marina’s rose garden. Marina and Miquelle fell in love, and knocked down the wall that separated their apartments. Today their house is a sanctuary for broken animals: a honey buzzard with damaged wings who sleeps on a perch in the coat room; a three-legged dog that Marina ran over with her truck and subsequently nursed back to health.

Miquelle and I sat in the living room, in front of his laptop, and he opened a folder labeled “Zolushka.” Inside were dozens of photographs—Zolushka in the banya; Zolushka on the operating table, her tail a bloody stump; Zolushka hopping out of her crate and into the Bastak Reserve. In later pictures, captured on the camera traps, she was strong, self-assured, completely at home in the wilderness. Finally, we came to the male: a thickset cat who had been given the name Zavetny.

Zavetny and Zolushka now seemed to be sharing a range, at one point apparently feasting together on the same kill. And on several occasions rangers have found “hump tracks”—evidence that Zavetny and Zolushka, who is now of breeding age, have mated.

Whether or not they have produced cubs isn’t yet known. But Miquelle is hopeful that one day very soon, he’ll receive a photo from a camera trap showing Zolushka with a line of cubs trailing behind.

It would be a milestone: the first rehabilitated tiger in history to mate and give birth in the wild. Miquelle smiled. “Wouldn’t it be amazing?” he asked.