Because of Climate Change, Canada’s Rocky Mountain Forests Are on the Move

Using century-old surveying photos, scientists have mapped 100 years of change in the Canadian Rockies to document the climate-altered landscape

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/90/1b/901b4a6b-8a41-44a2-807c-a8d2a7c76db8/main-canadian-rockies-mountains-trees-800x600.jpg)

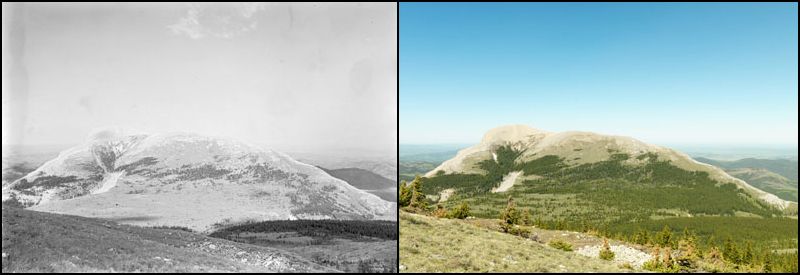

On an overcast day in 1927, surveyors Morrison Parsons Bridgland and Arthur Oliver Wheeler trekked up from the Owen Creek drainage in what is now Banff National Park to take a series of photos of the mountains along the North Saskatchewan River. They aimed to make the first accurate topographical maps of the region but in the process created something much bigger than they could have imagined.

Outwardly, the black-and-white photographs Bridgland and Wheeler took look like timeless shots of the Canadian Rockies. But new research using these old images is allowing a group of scientists with the Mountain Legacy Project to quantify a century of change in the landscape. Across the Canadian Rockies, forests are on the march.

The most recent results, published in the journal Scientific Reports, found tree lines extending higher and thicker than at the turn of the 20th century. These changes are helping scientists understand how ecosystems will continue to shift in a warming world.

Onward and Upward

In the late 1990s, scientists rediscovered Bridgland and Wheeler’s glass plate survey images at Library and Archives Canada in Ottawa. The 140,000-plus high-resolution negatives were taken in the late 1800s and early 1900s to precisely map the Canadian Rockies. A century later, they offer a unique time capsule to understanding ecological change.

“[We] kind of immediately recognized what a gold mine this was for science and for ecology, because you have this systematic coverage, during a period of time that we have really few data points,” said Andrew Trant, lead author on the new paper and an ecologist at the University of Waterloo.

On a sunny summer day 89 years after Bridgland and Wheeler lugged their surveying equipment into the mountains along the North Saskatchewan, scientists returned—except this time they reached the 2,590-meter ridgeline by helicopter and brought a modern, high-resolution digital camera. Stepping in the surveyors’ exact footprints, they carefully aligned and shot new photos that precisely replicated originals.

Using this technique, known as repeat photography, scientists trekked to summits and vantage points across the Canadian Rockies. They’ve now replicated 8,000 of these images, and comparisons with their counterparts taken a century ago are showing an evolving landscape. Notably, they’re showing a steady upward creep in tree line and forest density.

Tree lines—the upper limit in elevation or altitude beyond which trees cannot grow because of weather conditions—serve as visual boundaries of climate. Since tree lines evolve with shifts in weather patterns, they are useful in identifying how species are vulnerable to climate change.

“Tree lines have long been considered the canary in the coal mine for climate change,” said Melanie Harsch, a research affiliate at NOAA Fisheries who was not involved with the new work. “It is clear from the number of sites where trees have shifted from a shrub form to tree form, and tree density has increased, that climate change is impacting the Canadian Rockies.”

In addition to higher trees, the forests were also denser and contained fewer stunted, windswept trees known as krummholz.

The new results agree with previous research documenting how a changing climate will dramatically redistribute the world’s forests. Previous studies have found that climate change will induce forest-thinning droughts in the tropics. Models also predict heat waves at the poles will increase the zone of subalpine forests. Other field studies have found a piecemeal response around the world, with half of the sites surveyed showing advances in tree line.

“Going into it, we sort of expected something similar, where we find some areas that would have been responding and some areas not,” Trant said. “And what we saw was a fairly uniform response.”

The scientists think the difference might stem from fact that this study, although covering a vast area of the Canadian Rockies, isn’t a global analysis that covers diverse ecosystems. However, the difference might also be due to the usage of a longer timeline than other studies.

Although rising tree lines can be good for some forest species, it comes at a price for others. The encroachment of subalpine ecosystems threatens species that have lived in formerly alpine habitats for thousands of years, including trees such as whitebark pine, flowers such as moss campion, and birds such as Clark’s nutcracker.

“There are a lot of species, big charismatic species that we know and love, that depend on the alpine,” Trant said. “Grizzly bears do a lot of their denning in the alpine area, and caribou spend time there in the winter.”

With tens of thousands of images yet to reproduce, the Mountain Legacy Project hopes to continue documenting change across the Rockies in the years to come. Scientists are also using the data set to assess changes due to glacial recession, fire, and human activity. The possible projects that can be done with the images, Trant said, “are endless.”

This story was original published on Eos.org.