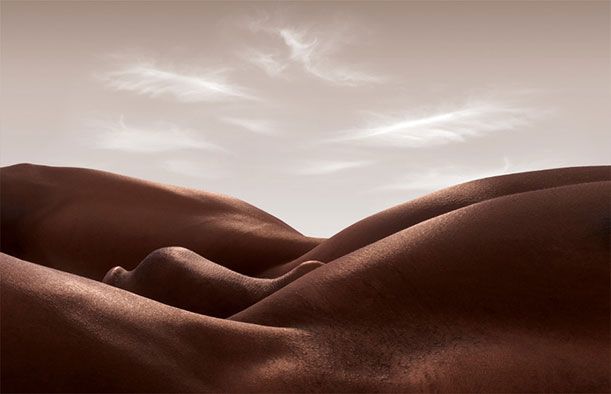

Carl Warner’s Mountains Are Made of Elbows and Knees

The British photographer creates convincing landscapes—deserts and rocky scenes—by piecing together photos of nude models

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130829095016Valley-of-the-reclining-woman-web.jpg)

Two and a half years ago, Carl Warner was building whimsical “foodscapes.” The British still life photographer has a knack for making coconuts look like haystacks; ribeye beef joints, like rock outcrops; and potatoes and soda bread, boulders. He even sculpted a London Skyline with a Parliament of green beans and a rhubarb-spoked London Eye.

Warner, however, has since moved on from food to another medium: the human body. “I’ve always been fascinated by the form and structure of the human body, so this was an experiment to see if I could create landscapes that would be as equally deceiving as the Foodscape work,” says the photographer.

Each landscape in the new series appears to include several bodies, and yet actually is created from photographs of a single person. “The scenes can simply be one shot of a part of their body or multiple shots that are composited together to make a more intricate scene,” Warner explains. “Once I have posed, lit and photographed the subject, I then take the image in to post production in order to grade and finesse it. I simply add a sky to the scene to give the image a sense of scale.”

The texture of his models’ skin and the shapes that they can make—a bent knee or elbow, an arched back and a flexed abdomen, for instance—give Warner the elements he needs to piece together a barren desert or rocky Moab-like setting. He sketches out a composition before each photo shoot, but inevitably, during the shoot, he sees other poses, which he incorporates into a new drawing. He shoots these unexpected elements to fit his new vision, often using both tungsten and flash lighting equipment to highlight the contours. “I try to re-create the feeling of natural sunlight in the studio, which enhances the sense of realism within the landscape,” says Warner.

In Photoshop, Warner pieces together the models’ limbs and contortions into finished landscapes. The photographer gives each scene a clever name: Valley of the Reclining Woman, Pectoral Dunes, Elbow Point and, my personal favorite, The Cave of Abdo-men.

Of course, the work comes with its challenges. “With the Foodscape work, I have a great palette of shapes, forms, textures and colors because of the variety of ingredients, but the human body has only the variety of skin types and ages,” says Warner. “There are probably only a certain amount of shapes and poses I can get from a body, and so the work may well be limited by the kind of landscape I can create in terms of structure and form. They are already limited in as much as they can only resemble desert or rocky terrain without vegetation.”

There is a sensual, almost carnal quality, no doubt, to the “bodyscapes.” Warner admits that the desert orgy scene from the film Zabriskie Point was a big inspiration for the series, though, he says, “I don’t consider these images to be about erotica.” Rather, there’s something almost geological about his work, where the folds and wrinkles mirror creases and gnarls in rock and sloping legs conjure images of weathered hills—organic representations of features devoid of life.

“These images are a different kind of portrait where the bodies we live in are being portrayed as a place we can visit,” says Warner. “I think that there is a sense of spiritual contemplation and peace about looking at ourselves in this way.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)