Caught in the Act: Scientists Find A T. Rex Tooth Stuck in a Hadrosaur Tail

The ancient attack proves once and for all that the T. Rex was a hunter, not just a scavenger

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130715020149DePalma-press-1-copy.jpg)

Recently, scientists have uncovered some pretty cool fossil finds from ancient times—a 23-million-year old lizard covered in amber, bony fish remnants that served as a microraptor’s final meal, and an entirely new dinosaur species discovered on the island of Madagascar.

Today’s discovery, though, might be the most remarkable of all: A group led by paleontologists David Burnham and Robert DePalma has discovered a Tyrannosaurus rex tooth crown wedged into the tail vertebrae of the plant-eating hadrosaur. What’s more, there’s fresh bone growth surrounding the tooth—indicating that the T. rex attacked the hadrosaur, took a bite and lost a tooth, but that the hadrosaur escaped to live another day.

The hadrosaur vertebrae fragment was excavated in South Dakota, from sediments of the Hell Creek Formation, a series of rock layers dating to between 100 and 56 million years old that are extremely rich in dinosaur fossils. The specimen (which dates to the Late Cretaceous epoch, between 100 and 66 million years ago) was discovered in 2010, but evidence of the embedded T. rex tooth was only revealed today, in a paper the researchers published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

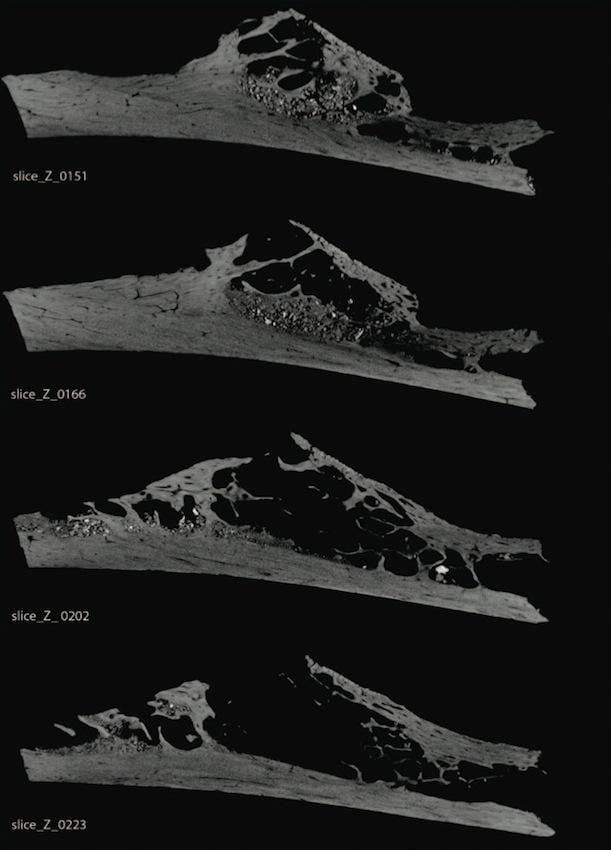

The specimen only consists of two vertebrae from a hadrosaur—a family of herbivorous creatures often called “duck-billed dinosaurs”—and likely comes from the species Edmontosaurus annectens in particular, based on the width, length and curvature of the two spinal bones. Upon close inspection, the researchers were able to find out a wealth of information from the small fragments of bone. Using manual examination and CT scanning, the team found that along with T. rex tooth, there was wounding at the site where it penetrated the vertebrae.

Additionally, bone had grown over the wound, fusing the two vertebrae together, and showing that the creature lived well past the moment of attack. It’s unclear exactly how long it would have taken for the bone growth to occur afterward, but they estimate a period of several years would have been necessary, based on scaled-up calculations of bone growth in modern reptiles.

Apart from the fact that it’s simply cool to see a prehistoric dinosaur attack preserved millions of years later in a fossil, the discovery also definitively answers a question about T. rex that paleontologists had been pondering for some time: Whether they actively hunted their prey, or merely scavenged dead corpses for meat.

Previously, other scientists had found T. rex stomach contents that included partially digested hadrosaur bones (PDF). Some paleontologists, though, argued that these bones merely showed that the T. rex ate its prey, but revealed nothing about whether it engaged in hunting or scavenging behavior beforehand. Despite the fact that calculations show T. rex had the strongest bite of any known animal—suggesting that it evolved for active hunting purposes—some hypothesized that the T. rex would have been too slow to be an effective hunter and that it would have been able to acquire enough calories simply by scavenging.

This new find, the researchers say, settles the issue once and for all. It may have also scavenged on the side, but the specimen shows that it hunted as well.

The T. rex clearly bit into a live hadrosaur, and the fact that the tooth was left in the hadrosaur’s tail makes the predatory behavior even more obvious—it’s easy to imagine the T. rex catching just the tail end of its prey as it ran away. And in this case, the T. rex’s lost meal is science’s gain.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)