Is China Ground Zero for a Future Pandemic?

Hundreds there have already died of a new bird flu, putting world health authorities on high alert

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0a/cc/0acc0a96-9b38-483a-b55f-bfe0bb414415/cong_birdflu_highres_2017_08_29_11.jpg)

Yin Shuqiang, a corn farmer in hardscrabble Sichuan province, sits on a rough-hewn wooden bench, surrounded by concrete walls. The only splash of color in his house is a crimson array of paper calligraphy banners around the family altar. It displays a wooden Buddhist deity and a framed black-and-white photograph of his late wife, Long Yanju.

Yin, who is 50 and wearing a neat gray polo shirt, is thumbing through a thick sheaf of medical records, pointing out all the ways physicians and traditional healers failed his wife. She was stricken by vomiting and fatigue this past March, but it took more than a week to determine she’d been infected by H7N9, an influenza virus that had jumped across the species barrier from birds to humans. By the time doctors figured out what was wrong with her, it was too late.

Long’s case is part of an ominous outbreak that began in China and could, according to experts in Asia and the United States, evolve into a pandemic. H7N9 first spread from birds to humans in 2013. Since then, there have been five waves of the virus. The fifth wave began in October 2016. By September 2017, it had infected 764 people—far more than any of the four preceding waves. Health officials recently confirmed that there have been 1,589 total cases of H7N9, with 616 of them fatal. “Anytime you have a virus with a 40 percent mortality rate,” says Tim Uyeki, the chief medical officer for the influenza division at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “that’s very, very serious.”

So far, the only verified means by which patients have acquired the virus is through direct exposure to infected animals. But if H7N9 were to mutate further and develop the ability to pass readily from person to person, it could spread rapidly and kill millions of people worldwide. The potential for disaster has normally cautious medical researchers expressing concern, even suggesting that H7N9 might rival the fierce influenza virus that caused the 1918 pandemic, which killed between 50 million and 100 million people.

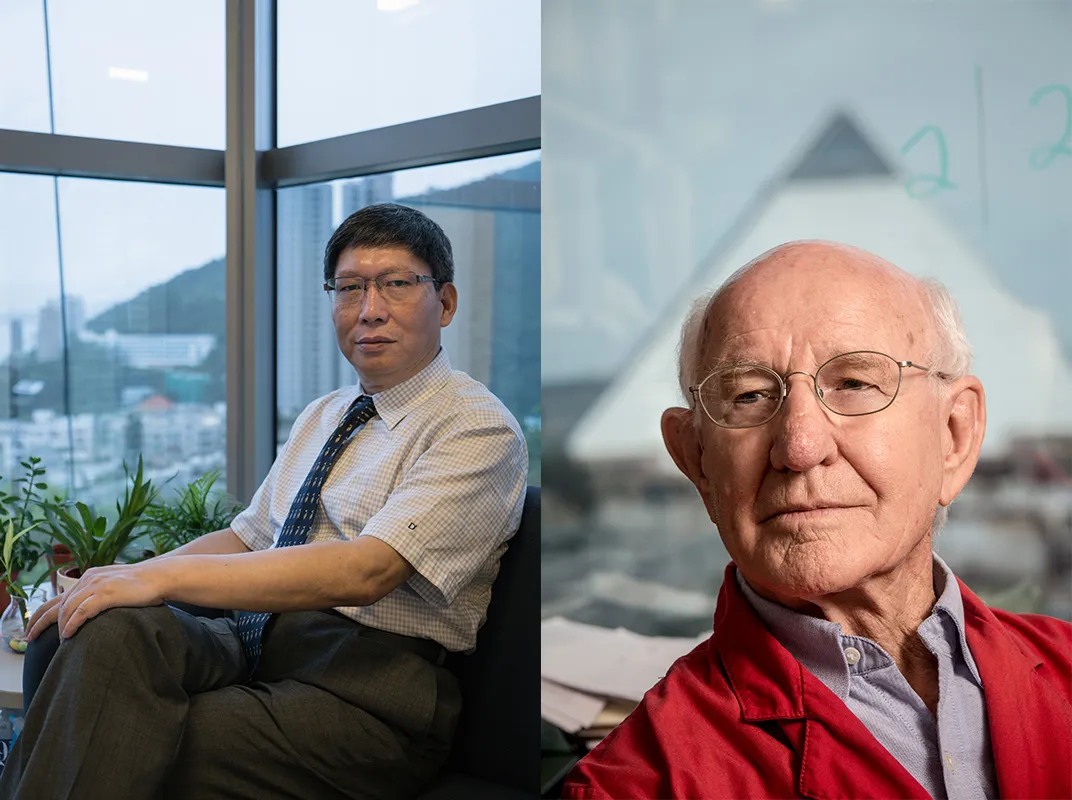

Guan Yi, a virus expert and noted flu hunter at the University of Hong Kong School of Public Health, has predicted that H7N9 “could be the biggest threat to public health in 100 years.” Specialists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned this past June that out of all the novel influenza strains they’d recently evaluated, H7N9 has the highest potential “to emerge as a pandemic virus and cause substantial human illness.”

Yin says he’d heard about H7N9 on TV, but when his wife started to vomit, they didn’t make the connection. Instead of seeking Western-style medicine, they did what many rural Chinese people do when they’re under the weather: They went to the local herbalist and sought inexpensive, traditional treatments for what they hoped was a simple illness. As a small-scale farmer with four children, Yin takes temporary construction jobs (as many rural Chinese do) to boost his income to about $550 a month. He had always been terrified that someone in his family might develop a serious health problem. “That’s a farmer’s worst nightmare,” he explains. “Hospital costs are unbelievable. Entire family savings could be wiped out.”

When the herbs didn’t work, Long’s family hired a car and drove her 20 miles to the Ziyang Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine. There she was diagnosed with gastrointestinal ulcers and received various treatments, including a medication often prescribed for colic and a traditional Chinese medicine (jingfang qingre) used to reduce fever. She didn’t improve. Two days later, Long went into intensive care. The next day, Yin was shocked when doctors told him his wife was, in fact, infected with H7N9.

The diagnosis was especially surprising, given that Long hadn’t done anything different than usual in the period leading up to her illness. She’d looked after her 73-year-old mother, who lived nearby, and worked in the cornfields. And just a few days before she became ill, Long had walked about an hour to the local market, approached a vendor selling live poultry and returned home with five chickens.

**********

Officially, the live-bird markets in Beijing have been shuttered for years. In reality, guerrilla vendors run furtive slaughterhouses throughout this national capital of wide avenues, gleaming architecture and more than 20 million residents—despite warnings that their businesses could be spreading deadly new strains of the flu.

In one such market, a man in sweatstained shorts had stacked dozens of cages—jammed with chickens, pigeons, quail—on the pavement outside his grim hovel.

I picked out two plump brown chickens. He slit their throats, tossed the flapping birds into a greasy four-foot-tall ceramic pot, and waited for the blood-spurting commotion to die down. A few minutes later he dunked the chickens in boiling water. To de-feather them, he turned to a sort of ramshackle washing machine with its rotating drum studded with rubber protuberances. Soon, feathers and sludge splashed onto a pavement slick with who knows what.

I asked the vendor to discard the feet. This made him wary. Chicken feet are a Chinese delicacy and few locals would refuse them. “Don’t take my picture, don’t use my name,” he said, well aware that he was breaking the law. “There was another place selling live chickens over there, but he had to shut down two days ago.”

Many Chinese people, even city dwellers, insist that freshly slaughtered poultry is tastier and more healthful than refrigerated or frozen meat. This is one of the major reasons China has been such a hot spot for new influenza viruses: Nowhere else on earth do so many people have such close contact with so many birds.

At least two flu pandemics in the past century—in 1957 and 1968—originated in the Middle Kingdom and were triggered by avian viruses that evolved to become easily transmissible between humans. Although health authorities have increasingly tried to ban the practice, millions of live birds are still kept, sold and slaughtered in crowded markets each year. In a study published in January, researchers in China concluded that these markets were a “main source of H7N9 transmission by way of human-poultry contact and avian-related environmental exposures.”

China Syndrome: The True Story of the 21st Century's First Great Epidemic

Deftly tracking a mysterious viral killer from the bedside of one of the first victims to China’s overwhelmed hospital wards—from cutting-edge labs where researchers struggle to identify the virus to the war rooms at the World Health Organization headquarters in Geneva—China Syndrome takes readers on a gripping ride that blows through the Chinese government’s effort to cover up the disease . . . and sounds a clarion call warning of a catastrophe to come: a great viral storm.

In Chongzhou, a city near the Sichuan provincial capital of Chengdu, the New Era Poultry Market was reportedly closed for two months at the end of last year. “Neighborhood public security authorities put up posters explaining why bird flu is a threat, and asking residents to co-operate and not to sell poultry secretly,” said a Chongzhou teacher, who asked to be identified only as David. “People pretty much listened and obeyed, because everyone’s worried about their own health.”

When I visited New Era Poultry in late June, it was back in business. Above the live-poultry section hung a massive red banner: “Designated Slaughter Zone.” One vendor said he sold some 200 live birds daily. “Would you like me to kill one for you, so you can have a fresh meal?” he asked.

Half a dozen forlorn ducks, legs tied, lay on a tiled and blood-spattered floor, alongside dozens of caged chickens. Stalls overflowed with graphic evidence of the morning’s brisk trade: boiled bird carcasses, bloodied cleavers, clumps of feathers, poultry organs. Open vats bubbled with a dark oleaginous resin used to remove feathers. Poultry cages were draped with the pelts of freshly skinned rabbits. (“Rabbit meat wholesale,” a sign said.)

These areas—often poorly ventilated, with multiple species jammed together—create ideal conditions for spreading disease through shared water utensils or airborne droplets of blood and other secretions. “That provides opportunities for viruses to spread in closely packed quarters, allowing ‘amplification’ of the viruses,” says Benjamin John Cowling, a specialist in medical statistics at the University of Hong Kong School of Public Health. “The risk to humans becomes so much higher.”

Shutting live-bird markets can help contain a bird flu outbreak. Back in 1997, the H5N1 virus traveled from mainland China to Hong Kong, where it started killing chickens and later spread to 18 people, leaving six dead. Hong Kong authorities shut down the city’s live-poultry markets and scrambled to cull 1.6 million chickens, a draconian measure that may have helped avert a major epidemic.

In mainland China, though, the demand for live poultry remains incredibly high. And unlike the Hong Kong epidemic, which visibly affected its avian hosts, the birds carrying H7N9 initially appeared healthy themselves. For that reason, shuttering markets has been a particularly hard sell.

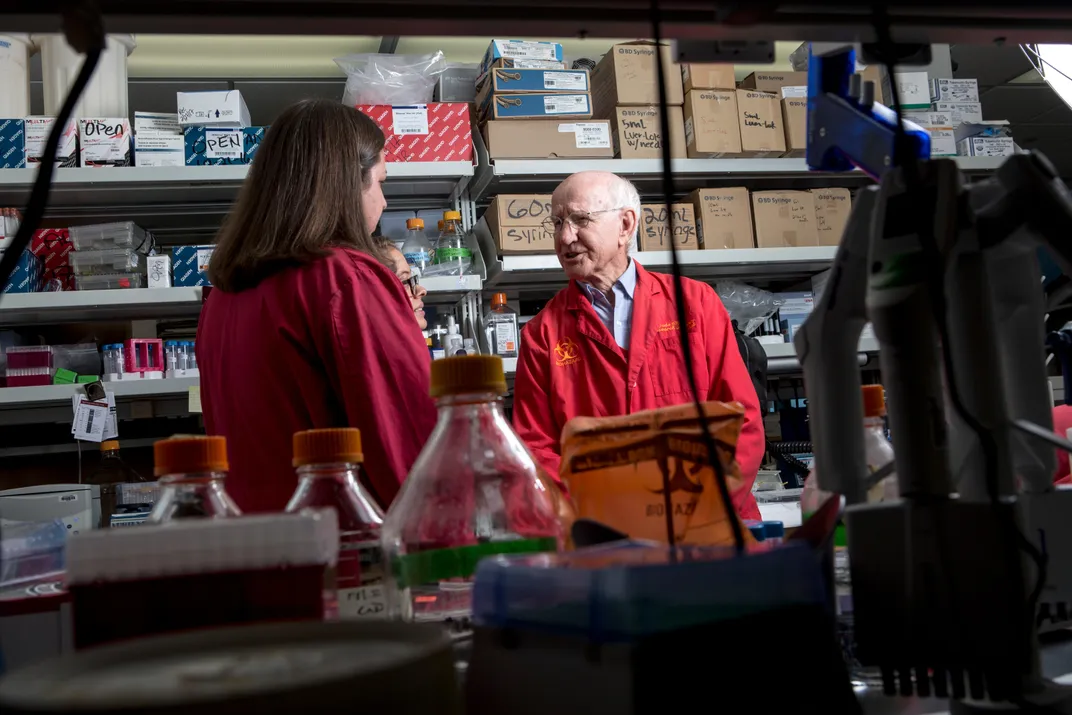

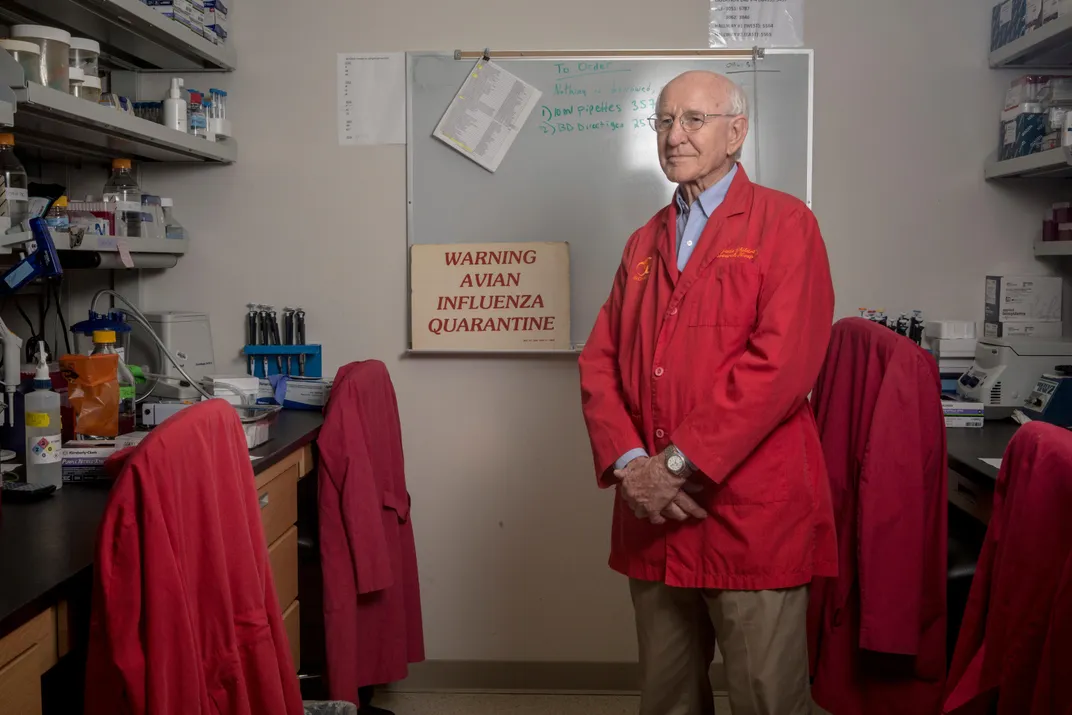

China’s Ministry of Agriculture typically hesitates to “mess with the industry of raising and selling chickens,” says Robert Webster, a world-renowned virologist based at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis. He has been working with Chinese authorities since 1972, when he was part of a Western public health delegation invited to Beijing. He and a colleague were eager to collect blood samples from Chinese farm animals. At a state-run pig farm, Webster recalls, he was allowed to get a blood sample from one pig. “Then we said, ‘Could we have more pigs?’ And the Chinese officials replied, ‘All pigs are the same.’ And that was it,” he concludes with a laugh. “It was a one-pig trip.”

The experience taught Webster something about the two sides of Chinese bureaucracy. “The public health side of China gave us absolute co-operation,” he says. “But the agricultural side was more reluctant.” He says the Chinese habit of keeping poultry alive until just before cooking “made some sense before the days of refrigeration. And now it’s in their culture. If you forcibly close down government live-poultry markets, the transactions will simply go underground.”

Tiny porcelain and wood figurines of chickens, geese and pigs dot a crowded windowsill in Guan Yi’s office at the School of Public Health, framing an idyllic view of green, rolling hills. Famed for his work with animal viruses, Guan is square-jawed and intense. Some call him driven. In another incarnation, he might have been a chain-smoking private investigator. In real life he’s a blunt-spoken virus hunter.

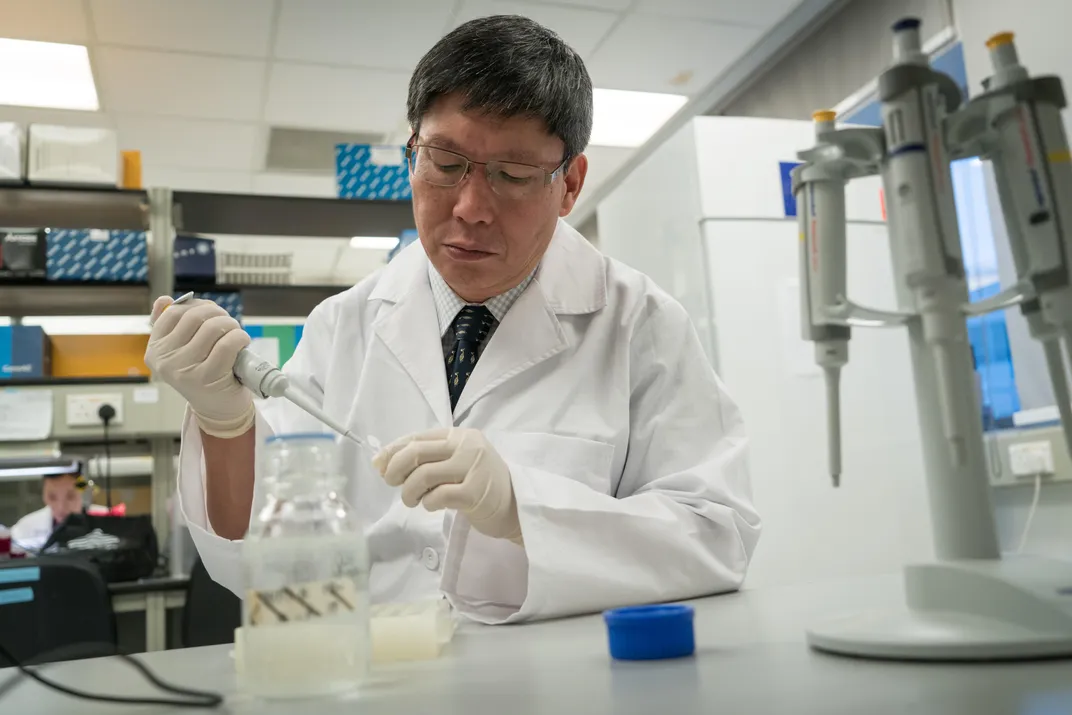

Working out of his Hong Kong base as well as three mainland Chinese labs, including one at Shantou University Medical College, Guan receives tips about unusual flu trends in China from grassroots contacts. He has trained several dozen mainland Chinese researchers to collect samples—mostly fecal swabs from poultry in markets and farms—and undertake virus extraction and analysis.

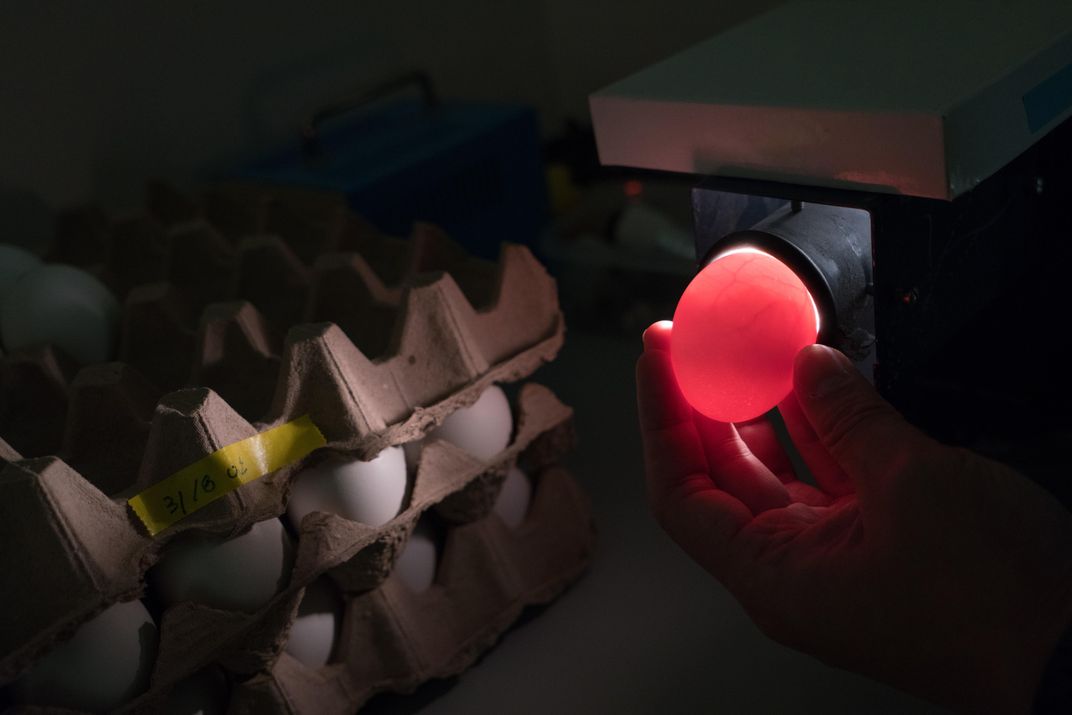

At a lab in Hong Kong, a colleague of Guan’s sits before rows of chicken eggs, painstakingly injecting droplets of virus-containing liquid into living embryos. Later the amniotic fluid will be analyzed. Another colleague shows off an important tool for their work: a sophisticated Illumina next-generation sequencing machine, which, he says, “can sequence genes at least 40 times faster” than the previous method.

Guan is concerned that H7N9 may be undergoing mutations that could make it spread easily between people. He’s alarmed that the most recent version of H7N9 has infected and killed so many more people than other avian flu viruses. “We don’t know why,” he frets.

Then there was that moment last winter when colleagues analyzing H7N9 were startled to discover that some of the viruses—previously non-pathogenic to birds—now were killing them. This virus mutation was so new that scientists discovered it in the lab before poultry vendors reported unusually widespread bird deaths.

Flu viruses can mutate anywhere. In 2015, an H5N2 flu strain broke out in the United States and spread throughout the country, requiring the slaughter of 48 million poultry. But China is uniquely positioned to create a novel flu virus that kills people. On Chinese farms, people, poultry and other livestock often live in close proximity. Pigs can be infected by both bird flu and human flu viruses, becoming potent “mixing vessels” that allow genetic material from each to combine and possibly form new and deadly strains. The public’s taste for freshly killed meat, and the conditions at live markets, create ample opportunity for humans to come in contact with these new mutations. In an effort to contain these infections and keep the poultry industry alive, Chinese officials have developed flu vaccines specifically for birds. The program first rolled out on a large scale in 2005 and has gotten mixed reviews ever since. Birds often spread new viruses without showing signs of illness themselves, and as Guan notes, “You can’t vaccinate every chicken in every area where bird flu is likely to emerge.” In July, after H7N9 was found to be lethal to chickens, Chinese authorities rolled out H7N9 poultry vaccines; it’s still too early to assess their impact.

Meanwhile, there is no human vaccine yet available that can guarantee protection against the most recent variant of H7N9. Guan’s team is helping pave the way for one. They’ve been looking deeply into the virus’ genesis and infection sources, predicting possible transmission routes around the globe. They’re sharing this information with like-minded researchers in China and abroad, and offering seasonal vaccine recommendations to international entities such as the World Health Organization and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Such data could prove life-saving—not just in China but worldwide—in the event of a full-on pandemic.

**********

When Long Yanju’s illness was diagnosed in April, she became one of 24 confirmed cases of H7N9 in Sichuan province that month. Hospitals there weren’t well equipped to recognize signs of the virus: This wave marked the first time H7N9 had traveled from the densely populated eastern coast westward to rural Sichuan. “With the spread across wider geographical areas, and into rural areas,” says Uyeki, the CDC influenza specialist, “it’s likely patients are being hospitalized where hospitals aren’t so well resourced as in the cities, and clinicians have less experience managing such patients.”

Yin is now alleging that the hospital committed malpractice for not properly diagnosing or treating his wife until it was too late. He initially asked for $37,000 in damages from the hospital. Officials there responded with a counterdemand that Yin pay an additional $15,000 in medical bills. “In late September I agreed to accept less than $23,000. I’d run out of money,” he says. “But when I went to collect, the hospital refused to pay and offered much less. It’s not enough.” A county mediation committee is trying to help both sides reach an agreement. (Hospital representatives declined to comment for this article.)

Whatever the outcome of Yin’s legal battle, it seems clear that shortcomings in the Chinese health care system are playing a role in the H7N9 epidemic. Along with rural people’s tendency to avoid Western-style medicine as too expensive, it’s routine for hospitals in China to demand payment upfront, before any tests or treatment takes place. Families are known to trundle ailing relatives on stretchers (or sometimes on stretched blankets) from clinic to clinic, trying to find someplace they can afford. “Everybody feels the same way as I do,” Yin says. “If the illness doesn’t kill you, the medical bills will.”

And any delay in receiving treatment for H7N9 is dangerous, physicians say. Although nearly 40 percent of people known to be infected with H7N9 have died so far, the odds of surviving may be much higher if medication such as the antiviral oseltamivir, known as Tamiflu, could be administered within 24 to 48 hours. “Chinese with H7N9 usually take two days to see a doctor, another four days to check into a hospital, and then on Day 5 or 6 they get Tamiflu,” says Chin-Kei Lee, the medical officer for emerging infectious diseases at the WHO China office. “Often people die within 14 days. So especially in rural areas, it’s hard to get treated in time—even if doctors do everything right.”

Though health authorities worldwide acknowledge that China is often an influenza epicenter, most Chinese people themselves don’t receive an annual flu shot. The logistics of administering mass vaccinations to a nation of more than one billion are daunting. While nearly half of Americans receive seasonal flu vaccinations, only about 2 percent of Chinese do. “Not enough,” admits Lee. “We always want to do better than yesterday.”

Earlier this year, Lee was one of 25 experts who gathered in Beijing under the umbrella of the United Nations to discuss the H7N9 threat. The meeting reviewed some of the measures in place at live-bird markets—such as mandatory weekly disinfection and bans on keeping poultry overnight—and concluded that they were insufficient.

Despite such shortcomings, Western experts say Chinese officials have come a long way since their wobbly handling of the 2002 outbreak of SARS, the severe respiratory disease caused by a previously unknown coronavirus; Chinese apparatchiks initially tried to cover up the epidemic, creating a worldwide scandal. But after the first H7N9 outbreak in 2013, Webster observes, Chinese authorities did “exactly what should have been done. You need to get the word out as fast as possible, with transparency and urgency, so the world can respond.”

Global cooperation is crucial. Along China’s southwestern underbelly lies a string of less developed countries such as Laos, Vietnam and Myanmar. (The last of these is of particular concern, since it imports large amounts of Chinese poultry.) Some of China’s border regions are themselves relatively impoverished, raising the possibility of persistent and recurring outbreaks on both sides of the rugged frontier.

“We need to be sure the whole world is prepared. There’s more than one country involved—and our response is only as strong as our weakest link,” warns Lee. China’s live-bird markets might seem exotic from a Western perspective.

But right now, one of those stalls could be brewing an even more deadly version of H7N9, one that could pass quickly through crowds of people in London and New York. As Lee says, “Viruses don’t need visas or passports. They just travel.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.