Climate Change’s Latest Victim: Canada’s Outdoor Ice Rinks

A new project asks citizens to monitor their backyard rinks, helping to track how a warming climate is affecting Canada’s skating tradition

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130215094156rink-small.jpg)

Of all the harmful effects of climate change—bigger storms, more severe droughts and sea level rise, for starters—a group of Canadian scientists have focused on one that hits particularly close to home: melting outdoor ice rinks.

Traditionally, Canada has been home to thousands of tiny backyard skating rinks; a huge number of hockey legends, including Wayne Gretzky, learned the game growing up on these rinks, which can either be custom-made or simply frozen-over ponds. But a report published last year by McGill University scientists looked at temperature data over time and warned that the length of skating season was rapidly contracting, testing the viability of outdoor skating in the future.

Until now, though, there was no centralized database on skating conditions at these sorts of rinks across North America. RinkWatch, a new program developed by professors and students from Ontario’s Wilfrid Laurier University that launched last month, aims to fill this void, asking rink owners and users across Canada and the US to report their own rinks’ conditions remotely.

Since the researchers started RinkWatch as a side project, it has exceeded their expectations, growing from 50 rinks to more than 425 in a matter of weeks. Robert McLeman, a professor of geography and environmental studies, told CBC that ”We launched on Jan. 8, and the phones lit up and the website crashed several times.”

They see the project as a logical use of citizen science to track how climate change is affecting backyard rinks over time. For the citizen scientists, the concept is simple. Each rink owner or user creates an account with RinkWatch and enters in his or her rink’s location. Each day, when the user logs on, a straightforward question pops up: “Were you able to skate today?” There are two possible answers: yes and no.

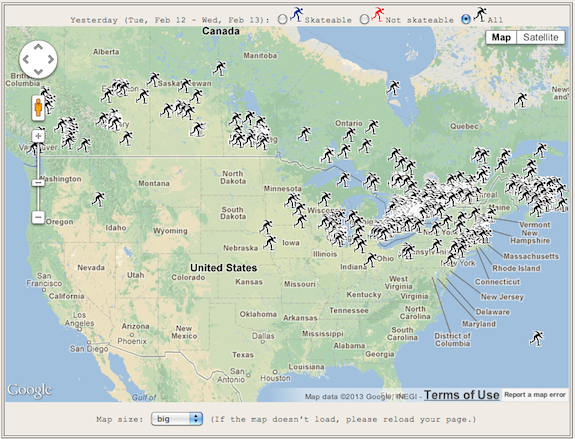

By enlisting skaters across the continent, the researchers hope to create a robust data set that will track how skating conditions are changing over time, rather than relying on anecdotal evidence. In the future, by looking for trends in when rinks first flood each spring and how many skateable weeks occur each winter, they might be able to use the length of the skating season as a marker to gauge how fast climate is changing. The project also includes a real-time map (accessible on its website) that indicates which areas of Canada and the U.S. are most hospitable to outdoor skating as of the previous day:

The McGill study that prompted the researchers to get involved is sure to strike fear into the heart of any outdoor hockey lover: Between 1950 and 2005, the estimated length of the outdoor skating season (based on temperature recordings) declined by 5 to 10 days in every region of Canada. After reading these results, McLeman and colleagues decided to start RinkWatch, focusing on the idea that the conditions of a backyard skating rink are a tangible—and personal—manifestation of climate change. “Everyone understands what’s going on in their backyard,” McLeman told CBC.

The scientists behind RinkWatch envision that their project will enable future studies to provide a more detailed look at how warming temperatures are affecting outdoor skating. Already, though, the project is bearing fruit: the team has published some data online, showing the percentage and number of rinks that were skatable across Canada during the month of January.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)