The Colorado River Delta Turned Green After a Historic Water Pulse

The experimental flow briefly restored the ancient waterway and may have created new habitat for birds

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b7/80/b780dfb5-82e5-4a1d-a922-c7a153649f43/pic_8.png)

For more than half a century, the mighty Colorado River has failed to regularly reach the sea. Its water has been dammed and diverted to feed vast farm fields and faraway cities, and the waterway that flowed for millions of years from the Rocky Mountains to the Gulf of California last swept through its vast delta 16 years ago.

Earlier this year, however, officials released an experimental pulse of 105,000 acre-feet of water from the Morelos Dam on the United States-Mexico border, and on May 15 the river once again flowed into the sea. The eight-week water release, though small, was enough to cause a 43 percent increase in green vegetation in the wetted zone and a 23 percent increase along the river’s borders, scientists reported this week at the American Geophysical Union's fall meeting in San Francisco.

“The pulse reversed a 13-year decline in vegetation,” said Pamela Nagler of the U.S. Geological Survey's Southwest Biological Science Center in Tucson, Arizona.

The water release was the outcome of a 2012 agreement between the United States and Mexico called Minute 319. It was intended to restore native vegetation and attract wildlife to the desiccated region. Since the release earlier this year, teams of researchers have monitored the area with ground- and satellite-based sensors.

Only a trickle of water reached the Gulf of California; most soaked into the ground within 37 miles of the Morelos Dam. But that water flowed into groundwater stores near the riverbed in the first seven days and dissipated over the next several weeks, gravity studies revealed.

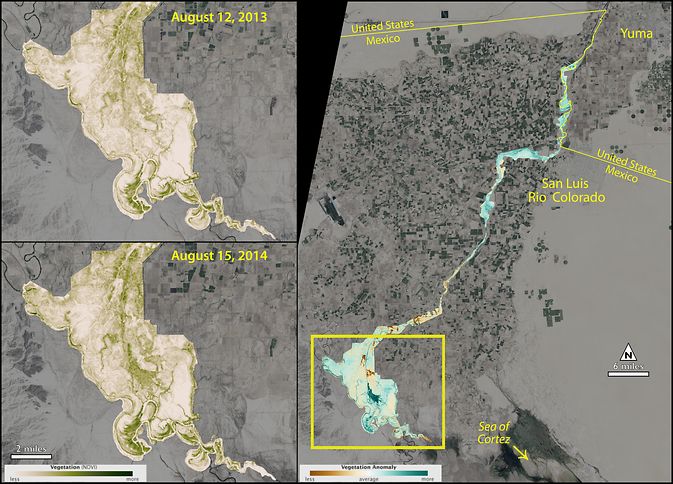

Comparisons of satellite imagery from August 2013 and August 2014 revealed the effects of the water flow—greening within the approximately 5,000 acres inundated by the pulse flow and also the larger riparian zone along the banks. The researchers detected an increase in vegetation even in areas downstream that did not receive much water. That greening was probably due to the movement of groundwater, Nagler says.

“The existing vegetation … has certainly benefitted from the flow,” says Karl Flessa, a geoscientist at the University of Arizona and co-chief scientist of the Minute 319 Science Team. “A lot of that vegetation is saltcedar,” a deciduous, non-native shrub. But some annuals may also have grown up as a result of the water inundation, he says.

Researchers will continue to monitor the effects on the delta through 2017. Areas where the flow let seeds for long-lived trees such as cottonwoods and willows germinate—and where those new plants survived the harsh summer—could see long-term benefits, says Flessa.

The impact of the water release on bird populations is still unknown, but Flessa says that both resident and migratory birds probably benefitted from the inundation. The delta is located along the Pacific Flyway, a major migratory route in the western United States, he noted, and “birds traveling north and south presumably will benefit from the increased quality of the habitat there.”

Even though the pulse flow appears to have benefitted the local ecology, similar releases of water cannot take place without further negotiations between the United States and Mexico. The river’s water is fully allocated to municipal and agricultural use, Flessa notes, but researchers hope that more environmental flows will take place in the future.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)