Cops Could Soon Use Breathalyzers to Test for Illegal Drugs

Swedish researchers are developing a system that tests for 12 different drugs on your breath, including cocaine, marijuana and amphetamines

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130426073141breathalyzer-small.jpg)

Your breath says a lot about you. Recent research has found that the chemicals present in each person’s breath can provide a unique “breathprint” that differs from person to person, while other scientists have worked on breathalyzer-like tests that can indicate the presence of a bacterial infection inside someone’s body.

In the decades since the 1960s, though, when the first electronic breathalyzer for blood alcohol content was developed, research has led to relatively little advancement in the use of chemical breath analysis for law enforcement purposes. Police have long been able to instantly test a person’s level of alcoholic intoxication by the side of a road, but testing for other drugs has required blood or saliva—substances that are more invasive acquire and that typically have to be sent to a crime lab for processing. Both factors make it difficult to figure out who’s under the influence at, say, the scene of a car accident right after it occurs.

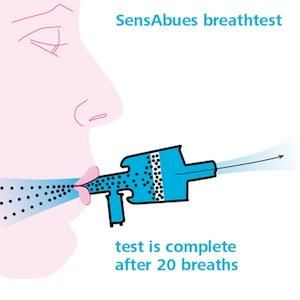

But new research suggests that the status quo might be changing in a hurry. A study published yesterday in the Journal of Breath Research reveals that scientists can now use breath analysis to test for the presence of 12 different drugs in the body, including cocaine, marijuana and amphetamines. Previous work has shown that such technology can reliably test for several of these drugs, and this new study is the first time the drugs alprazolam (commercially known as Xanax, useful for treating anxiety disorders) and benzoylecgonine (a topical pain killer) have been detected. Members of the research group, from Sweden’s Karolinska Institutet, have already created a commercially-available breath testing system, called SensAbues—and it’s easy to speculate that law enforcement across the U.S. (and around the world) would love to get their hands on such technology as soon as possible.

The research team, led by Olof Beck, conducted the new study by testing the breath of 46 individuals who were checked into a drug addiction emergency clinic, had taken drugs about 24 hours earlier and volunteered to participate in the study. Each participant exhaled about 20 deep breaths into the SensAbues filter (which takes 2-3 minutes), and the solid and liquid microparticles suspended in their breath were trapped on a disk for analysis.

These tiny quantities of microparticles reflect the substances in a person’s bloodstream, because small amounts of the molecules from our blood diffuse into the fluid that lines our lungs’ bronchioles and then into our breath. By isolating these particles and analyzing them with liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry, the research team was able to determine the drugs present in each person’s body with a decent level of accuracy.

They compared the results to blood and urine samples taken from each of the participants, as well as their own reports of what drugs they’d taken in the previous 24 hours, and on the whole, the tests performed pretty well—although some progress clearly still needs to be made. All 46 people had reported taking one of the 12 detectable illegal substances, and drugs were detected in the breath of 40 of them (87 percent). Most of the particular drugs detected matched with self-reports and blood tests, but 23 percent of the time, the breath tests also indicated the presence of a drug that hadn’t actually been taken. This level of accuracy was higher than previous studies the team has done, as they’ve slowly refined the system to cut down on false positives and improve the detection rate.

Currently, using the SensAbues system would only allow officials to collect a sample and send it elsewhere for analysis. But the researchers say that advances in the cost and portability of chemical analysis could eventually allow for the same sort of roadside breath testing for drugs that we currently have for alcohol.

Another scientific hurdle is data: Unlike for alcohol, we still don’t know what a given quantity of drug molecules detected on someone’s breath means in terms of how much of the drug is actually in their bloodstream (although an accurate detection of any illegal substance might be all law enforcement officials may be after). We also don’t know how long traces of these drugs remain on a person’s breath, and how quickly they degrade.

If scientists are able to make some progress in figuring this all out, though—and if they can make the testing procedure more accurate—roadside drug tests could become a routine part of law enforcement protocol.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)