This Coral Restoration Technique Is ‘Electrifying’ a Balinese Village

The technique is also changing attitudes and inspiring locals to preserve their natural treasures

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d1/ee/d1eed223-f24c-4035-8a34-80d375af251b/coral_goddess_and_snapper.jpg)

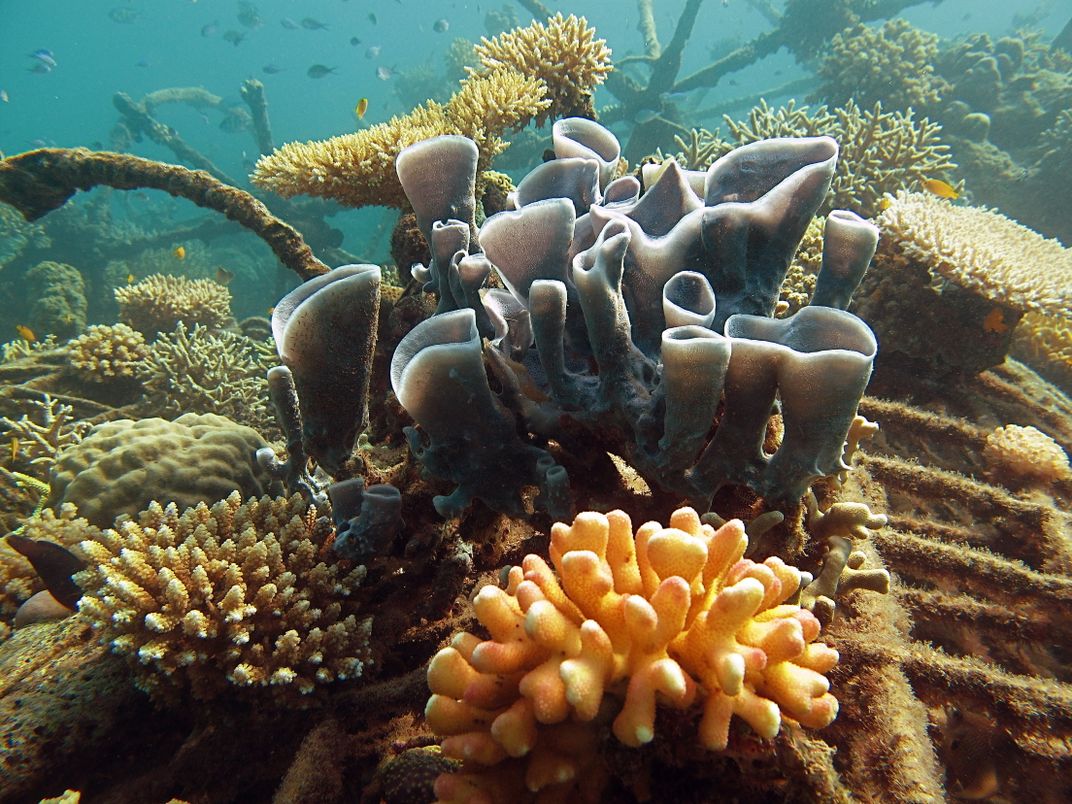

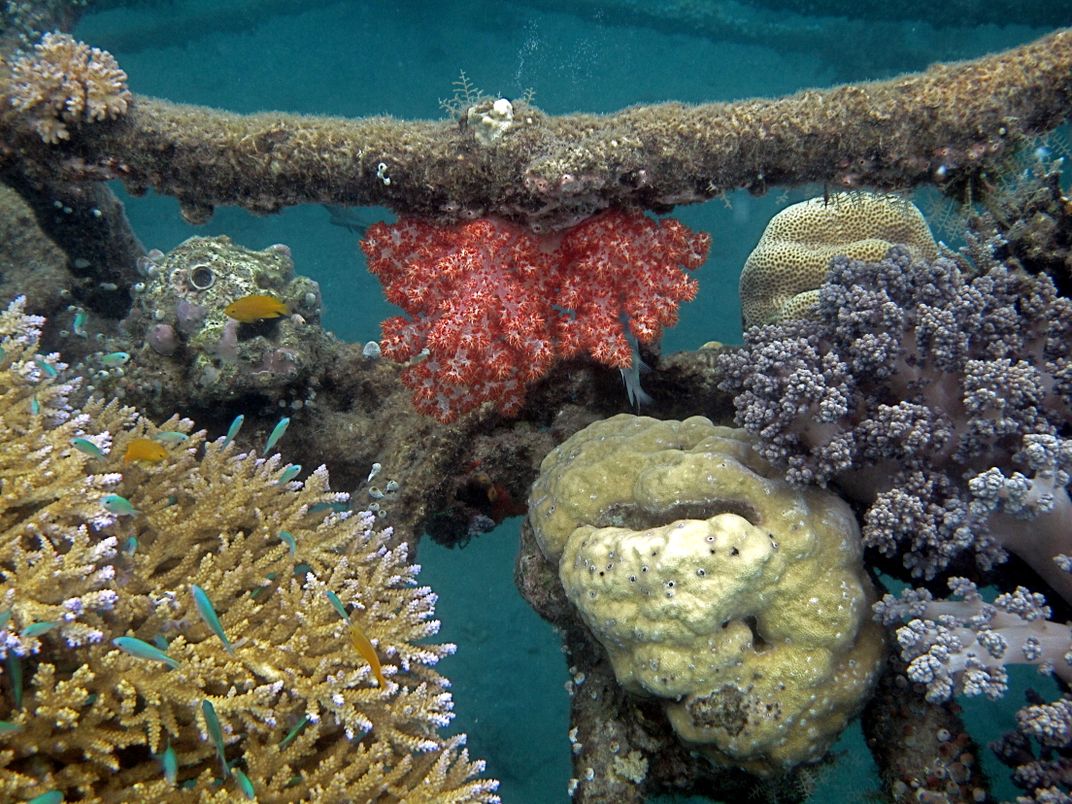

As you walk the beach in Pemuteran, a tiny fishing village on the northwest coast of Bali, Indonesia, be careful not to trip on the power cables snaking into the turquoise waves. At the other end of those cables are coral reefs that are thriving with a little help from a low-voltage electrical current.

These electrified reefs grow much faster, backers say. The process, known as Biorock, could help restore these vital ocean habitats at a critical time. Warming waters brought on by climate change threaten many of the world’s coral reefs, and huge swaths have bleached in the wake of the latest El Niño.

Skeptics note that there isn’t much research comparing Biorock to other restoration techniques. They agree, however, that what’s happening with the people of Pemuteran is as important as what’s going on with the coral.

Dynamite and cyanide fishing had devastated the reefs here. Their revival could not have succeeded without a change in attitude and the commitment of the people of Pemuteran to protect them.

Pemuteran is home to the world’s largest Biorock reef restoration project. It began in 2000, after a spike in destructive fishing methods had ravaged the reefs, collapsed fish stocks and ruined the nascent tourism industry. A local scuba shop owner heard about the process and invited the inventors, Tom Goreau and Wolf Hilbertz, to try it out in the bay in front of his place.

Herman was one of the workers who built the first structure. (Like many Indonesians, he goes by just one name.) He was skeptical.

“How (are we) growing the coral ourselves?” he wondered. “What we know is, this belongs to god, or nature. How can we make it?”

A coral reef is actually a collection of tiny individuals called polyps. Each polyp lays down a layer of calcium carbonate beneath itself as it grows and divides, forming the reef’s skeleton. Biorock saves the polyps the trouble. When electrical current runs through steel under seawater, calcium carbonate forms on the surface. (The current is low enough that it won’t hurt the polyps, reef fish or divers.)

Hilbertz, an architect, patented the Biorock process in the 1970s as a way to build underwater structures. Coral grows on these structures extremely well. Polyps attached to Biorock take the energy they would have devoted to building calcium carbonate skeletons and apply it toward growing, or warding off diseases.

Hilbertz's colleague Goreau is a marine scientist, and he put Biorock to work as a coral-restoration tool. The duo says that electrified reefs grow from two to six times faster than untreated reefs, and survive high temperatures and other stresses better.

Herman didn’t believe it would work. But, he says, he was “just a worker. Whatever the boss says, I do.”

So he and some other locals bought some heavy cables and a power supply. They welded some steel rebar into a mesh frame and carried it into the bay. They attached pieces of living coral broken off other reefs. They hooked it all up. And they waited.

Within days, minerals started to coat the metal bars. And the coral they attached to the frame started growing.

“I was surprised,” Herman says. “I said, damn! We did this!”

“We started taking care of it, like a garden,” he adds. “And we started to love it.”

Now, there are more than 70 Biorock reefs around Pemuteran, covering five acres of ocean floor.

But experts are cautious about Biorock’s potential. “It certainly does appear to work,” says Tom Moore, who leads coral restoration work in the U.S. Caribbean for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

However, he adds, “what we’ve been lacking, and what’s kept the scientific community from embracing it, is independent validation.” He notes that nearly all the studies about Biorock published in the scientific literature are authored by the inventors themselves.

And very little research compares growth rates or long-term fitness of Biorock reefs to those restored by other techniques. Moore’s group has focused on restoring endangered staghorn and elkhorn corals. A branch snipped off these types will grow its own branches, which themselves can be snipped and regrown.

He says they considered trying Biorock, but with the exponential expansion they were doing, “We were growing things plenty fast. Growing them a little faster wasn’t going to help us.”

Plus, the need for a constant power supply limits Biorock’s potential, he adds. But climate change is putting coral reefs in such dire straits that Biorock may get a closer look, Moore says.

The two endangered corals his group works on “are not the only two corals in the [Caribbean] system. They’re also not the only two corals listed under the Endangered Species Act. We’ve had the addition of a number of new corals in the last two years.” These slower-growing corals are harder to propagate.

“We’re actively looking for new techniques,” Moore adds. That includes Biorock. “I want to keep a very much open mind.”

But there’s one thing he’s sure about. “Regardless of my skepticism of whether Biorock is any better than any of the other techniques,” he says, “it’s engaging the community in restoration. It’s changing value sets. [That’s] absolutely critical.”

Pemuteran was one of Bali’s poorest villages. Many depend on the ocean for subsistence. The climate is too dry to grow rice, the national staple. Residents grow corn instead, but “only one time a year because we don’t get enough water,” says Komang Astika, a dive manager at Pemuteran’s Biorock Information Center, whose parents are farmers. “Of course it will not be enough,” he adds.

Chris Brown, a computer engineer, arrived in Pemuteran in 1992 in semi-retirement. He planned to, as he put it, trade in his pinstripe suit for a wetsuit and become a dive instructor.

There wasn’t much in Pemuteran back then. Brown says there were a couple good reefs offshore, “but also a lot of destruction going on, with dynamite fishing and using potassium cyanide to collect aquarium fish.” A splash of the poison will stun fish. But it kills many more, and it does long-lasting damage to the reef habitat.

When he spotted fishermen using dynamite or cyanide, he’d call the police. But that didn’t work too well at first, he says.

“In those days the police would come and hesitantly arrest the people, and the next day they’d be [released] because the local villagers would come and say, ‘that’s my family. You’ve got to release them or we’ll [protest].’”

But Brown spent years getting to know the people of Pemuteran. Over time, he says, they grew to trust him. He remembers a pivotal moment in the mid-1990s. The fisheries were collapsing, but the local fishermen didn’t understand why. Brown was sitting on the beach with some local fishermen, watching some underwater video Brown had just shot.

One scene showed a destroyed reef. It was “just coral rubble and a few tiny fish swimming around.” In the next scene, “there’s some really nice coral reefs and lots of fish. And I’m thinking, ‘Oh no, they’re going to go out and attack the areas of good coral because there’s good fish there.’”

That’s not what happened.

“One of the older guys actually said, ‘So, if there’s no coral, there’s no fish. If there’s good coral, there’s lots of fish.’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ And he said, ‘So we’d better protect the good coral because we need more fish.’

“Then I thought, ‘These people aren’t stupid, as many people were saying. They’re just educated differently.’”

It wasn’t long before the people of Pemuteran would call the police on destructive fishermen.

But sometimes, Brown still took the heat.

Once, when locals called the police on cyanide fishers from a neighboring village, Brown says, people from that village “came back later with a big boat full of people from the other village wielding knives and everything and yelling, ‘Bakar, bakar!’ which means ‘burn, burn.’ They wanted to burn down my dive shop.”

But the locals defended Brown. “They confronted these other [fishermen] and said, ‘It wasn't the foreigner who called the police. It was us, the fishermen from this village. We’re sick and tired of you guys coming in and destroying [the reefs].’”

That’s when local dive shop owner Yos Amerta started working with Biorock’s inventors. The turnaround was fast, dramatic and effective. As the coral grew, fish populations rebounded. And the electrified reefs drew curious tourists from around the world.

One survey found that “forty percent of tourists visiting Pemuteran were not only aware of village coral restoration efforts, but came to the area specifically to see the rejuvenated reefs,” according to the United Nations Development Program. The restoration work won UNDP’s Equator Prize in 2012, among other accolades.

Locals are working as dive leaders and boat drivers, and the new hotels and restaurants offer another market for the locals' catch.

“Little by little, the economy is rising,” says the Biorock Center’s Astika. "[People] can buy a motorbike, [children] can go to school. Now, some local people already have hotels.”

Herman, who helped build the first Biorock structure, now is one of those local hotel owners. He says the growing tourism industry has helped drive a change in attitudes among the people in Pemuteran.

“Because they earn money from the environment, they will love it,” he says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Baragona_headshot_s.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Baragona_headshot_s.jpg)