Cosmic Portraits Created From Hubble Space Telescope Images

Sergio Albiac generates images of people by collecting their head shots and replacing pixels with snippets from pictures of stars and galaxies

© Sergio Albiac

In less than 60 days, artist Sergio Albiac has created more than 11,000 portraits. This kind of productivity, no doubt, seems unfathomable—until you consider his artistic method.

Albiac is a practitioner of generative art, a discipline in which artists employ non-human assistants—often computers—to make aesthetic decisions. “An artist has the potential to create infinite artworks but only some of them will see the light due to the constraint of time,” says the artist on his website. “What if we use technology to outsource the creation of art so more of these potential artworks are finally created?”

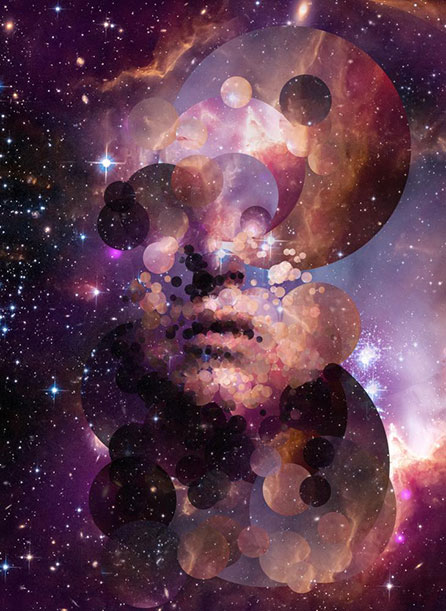

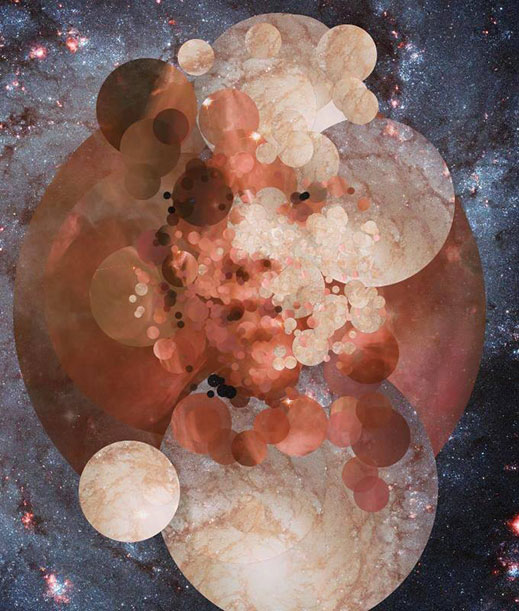

For his latest project, “Stardust Portraits,” Albiac, a computer science engineer with a background in art and art history, wrote software that can take a photographic portrait submitted by the public and recreate it as a cosmic mosaic of Hubble space telescope images.

“Starting with the photo as reference, the software randomnly chooses two Hubble images from a predetermined set,” says Albiac, who is based in Barcelona. He hand-selected about 50 images from the Hubble site for his color palette. ”Then, it uses a technique that I call ‘generative collage,’” he adds. “It finds random sections of the Hubble photo that ‘resemble’ areas of the original photo.” Ultimately, the software replaces every single pixel of the original portrait with a tidbit of stars and galaxies from the Hubble images.

The orbs in each portrait, whether an aesthetic choice or fundamental to the software’s code, nonetheless reflect an important theme of this project—how we are all made up of smaller pieces through the “creation of new atomic nuclei from pre-existing matter that takes place at cosmic scale,” Albiac explains on his site. “We humans are believed to be novel combinations of cosmic stardust,” he says. In fact, “It could be argued that the whole universe is the biggest running generative art installation today.”

As an artist, Albiac is interested in the “controlled chance” of what he calls his “truly contemporary medium.” He has control over the technique in that he personally designs the software, and yet there is this element of random, in the way that the program, using algorithms, generates the collages. Albiac thinks the interplay between control and randomness and computer and human interaction is poetic. He is also intrigued by how generative art can allow artists to be much more prolific, and, as long as the software survives, create work long after they die.

In the past, Albiac has created generative portraits of famous poets and composers from excerpts of their manuscripts and sheet music. He calls them “self portraits.” He also produced a series where visages appear in clever arrangements of newsprint.

“Creativity is infinite,” says Albiac. For “Stardust Portraits,” the artist chose to piece portraits together using images collected from the Hubble telescope because the images seemed to align with this theme. “New ideas are the result of combinations and processing of existing ideas, as new matter is a cosmic combination of existing matter. Everything is connected, recycled, reformulated, forever,” he says.

The project relies on the generosity of strangers submitting photographs of themselves. To participate, Albiac asks that you upload a head shot (in jpg format) to a Google Drive cloud storage and share it with [email protected], specifying a “can edit” access level. In about three days time, Albiac promises to send you three “stardust” portraits generated from the original photo.

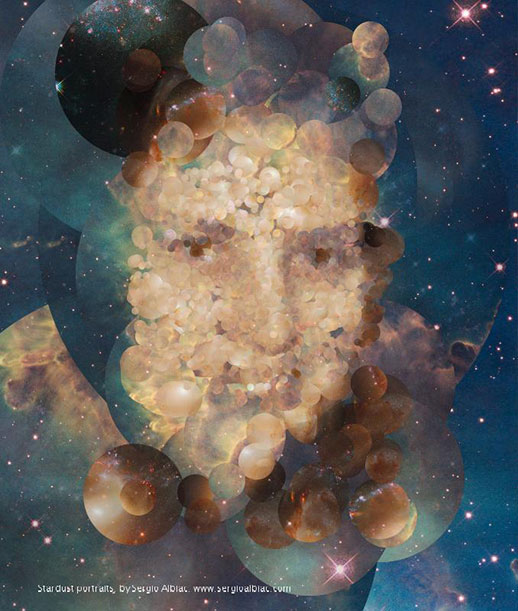

Curious as to what Albiac’s software would generate, I submitted my own photo to the project. Within days, I received this “stardust” portrait, above. The resemblance is striking. Though it contains not one pixel of my original portrait, Albiac’s version is recognizable; I am looking into my eyes.

I am not sure the portrait raised new questions for me or changed my view of myself—a grandiose goal, Albiac admits. But, I have to say, seeing it did fill the artist’s most basic desire.

“Just an instant of happiness is enough,” says Albiac.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)