Could “Magic” Mushrooms Be Used to Treat Anxiety and Depression?

Emerging research indicates that low doses of the active chemical psilocybin, found in the fungi, can have positive psychiatric effects

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Surprising-Science-Magic-Mushrooms-631.jpg)

In the 1960s and early 70s, researchers such as Harvard’s Timothy Leary enthusiastically promoted the study of so-called “magic” mushrooms (formally known as psilocybin mushrooms) and championed their potential benefits for psychiatry. For a brief moment, it seemed that controlled experiments with mushrooms and other psychedelics would enter the scientific mainstream.

Then, everything changed. A backlash against the 1960s’ drug culture—along with Leary himself, who was arrested for drug possession—made research nearly impossible. The federal government criminalized mushrooms, and research ground to a halt for over 30 years.

But recently, over the past few years, the pendulum has swung back in the other direction. And now, new research into the mind-altering chemical psilocybin in particular—the hallucinogenic ingredient in “magic” mushrooms—has indicated that carefully controlled, low doses of it might be an effective way of treating people with clinical depression and anxiety.

The latest study, published last week in Experimental Brain Research, showed that dosing mice with a purified form of psilocybin reduced their outward signs of fear. The rodents in the study had been conditioned to associate a particular noise with the feeling of being electrically shocked, and all the mice in the experiment kept freezing in fear when the sound was played even after the shocking apparatus was turned off. Mice who were given low doses of the drug, though, stopped freezing much earlier on, indicating that they were able to disassociate the stimuli and the negative experience of pain more easily.

It’s difficult to ask a tortured mouse why exactly it feels less fearful (and presumably even more difficult when that mouse is in the midst of a mushroom trip). But a handful of other recent studies have demonstrated promising effects of psilocybin on a more communicative group of subjects: humans.

In 2011, a study published in the Archives of General Psychiatry by researchers from UCLA and elsewhere found that low doses of psilocybin improved the moods and reduced the anxiety of 12 late-stage terminal cancer patients over a long period. These were patients aged 36 to 58 who suffered from depression and had failed to respond to conventional medications.

Each patient was given either a pure dose of psilocybin or a placebo, and asked to report their levels of depression and anxiety several times over the next few months. Those who’d been dosed with psilocybin had lower anxiety levels at one and three months, and reduced levels of depression starting two weeks after treatment and continuing for a full six months, the entire period covered by the study. Additionally, carefully administering low doses and controlling the environment prevented any participants from having a negative experience while under the influence (colloquially, a “bad trip.”)

A research group from Johns Hopkins has conducted the longest-running controlled study of the effects of psilocybin, and their findings might be the most promising of all. In 2006, they gave 36 healthy volunteers (who’d never before tried hallucinogens) a dose of the drug, and 60 percent reported having a “full mystical experience.” 14 months later, the majority reported higher levels of overall well-being than before and ranked taking psilocybin as one of the five most personally significant experiences of their lives. In 2011, the team conducted a study with a separate group, and when members of that group were questioned a full year later, the researchers found that according to personality tests, the participants’ openness to new ideas and feelings had increased significantly—a change seldom seen in adults had increased.

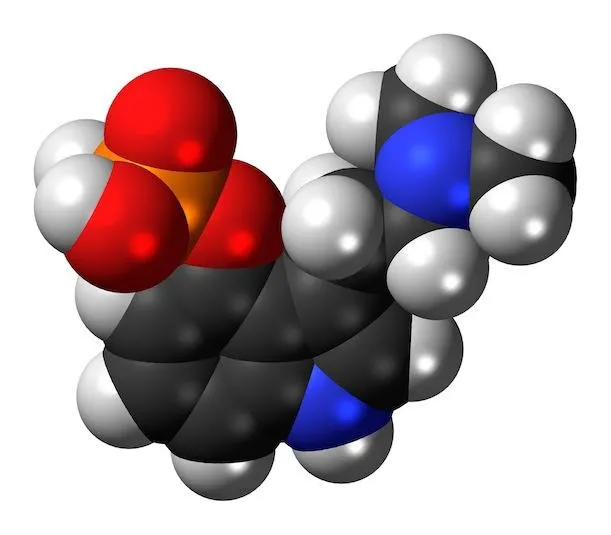

As with many questions involving the functioning of the mind, scientists are still in the beginning stages of figuring out whether and how psilocybin triggers these effects. We do know that soon after psilocybin is ingested (whether in mushrooms or in a purified form), it’s broken down into psilocin, which stimulates the brain’s receptors for serotonin, a neurotransmitter believed to promote positive feelings (and also stimulated by conventional anti-depressant drugs).

Imaging of the brain on psilocybin is in its infancy. A 2012 study in which volunteers were dosed while in an fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) machine, which measures blood flow to various parts of the brain, indicated that the drug decreased activity in a pair of “hub” areas (the medial prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex), which have dense concentrations of connections with other areas in the brain. “These hubs constrain our experience of the world and keep it orderly,” David Nutt, a neurobiologist at the Imperial College London and lead author, said at the time. “We now know that deactivating these regions leads to a state in which the world is experienced as strange.” It’s unclear how this could help with depression and anxiety—or whether it’s simply an unrelated consequences of the drug that has nothing to do with its beneficial effects.

Regardless, the push for more research into the potential applications of psilocybin and other hallucinogens is clearly underway. Wired recently profiled the roughly 1,600 scientists who attended the 3rd annual Psychedelic Science meeting, many of which are studying psilocybin—along with other drugs like LSD (a.k.a. “acid”) and MDMA (a.k.a. “ecstasy”).

Of course, there’s an obvious problem with using psilocybin mushrooms as medicine—or even researching its effects in a lab setting. Currently, in the U.S., they’re listed as a “Schedule I controlled substance,” meaning that they’re illegal to buy, possess, use or sell, and can’t be prescribed by a doctor, because they have no accepted medical use. The research that has occurred went on under strict government supervision, and getting approval for new studies is notoriously difficult.

That said, the fact that research is occurring at all is an obvious sign that things are slowly changing. The idea that medicinal use of marijuana would one day be permitted in dozens of states would have once seemed far-fetched—so perhaps it’s not entirely absurd to suggest that medicinal mushrooms could be next.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)