Could Sewage Be Our Fuel of the Future?

A new way of treating wastewater uses bacteria to produce electricity, potentially solving a pair of environmental problems

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/WasteWater-hero-631.jpg)

As we ponder how we’re going to supply the world’s increasing energy needs over the course of the 21st century, the discussion usually swings between fossil fuels such as coal, oil and natural gas, and emerging alternative energy sources such as wind and solar power. Increasingly, though, scientists and engineers are looking at the possibility of tapping into an unlikely fuel source to generate electricity: the wastewater that we routinely flush down the drain.

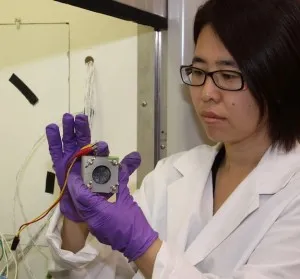

Earlier this week, Oregon State University engineers announced a new advance in microbial fuel cells that generate electricity from wastewater. As described in an article in the journal Energy and Environmental Science, they have developed a technology that uses bacteria to harvest energy from the biodegradable components of sewage at a rate that is 10 to 50 times more efficient than previous methods.

“If this technology works on a commercial scale the way we believe it will, the treatment of wastewater could be a huge energy producer, not a huge energy cost,” said Hong Liu, one of the authors of the study. “This could have an impact around the world, save a great deal of money, provide better water treatment and promote energy sustainability.”

Currently, conventional methods used to treat wastewater consume a great deal of energy—roughly three percent of all electricity used in the country, experts estimate. If scientists are able to figure out an efficient way to generate electricity as part of the process, they could turn this equation on its head. The concept has been around for some time, but only recently have practical advances brought us closer to employing the principle commercially.

Previous methods relied upon anaerobic digestion, in which bacteria break down biodegradable elements in wastewater in the absence of oxygen and produce methane (natural gas) as a byproduct. This gas can then be collected and burned as fuel.

The Oregon State team’s technology, in contrast, harnesses the biodegradable material in wastewater to feed aerobic bacteria, which digest the substances with the use of oxygen. When the microbes oxidize these components of sewage—and, in turn, clean the water—they produce a steady stream of electrons. As the electrons flow from the anode to the cathode within a fuel cell, they produce an electrical current, which can be directly used as a power source. Additionally, this process cleans the water more effectively than anaerobic digestion and doesn’t produce unwanted byproducts.

In the lab, the team’s setup—which improves upon previous designs with more closely spaced anodes and cathodes and a new material separation process that isolates the organic content of wastewater in a more concentrated form—produced more than two kilowatts per cubic meter of wastewater, a significantly greater amount than previous anaerobic digestion technologies. For comparison, the average U.S. household uses approximately 1.31 kilowatts of electricity at any given time. The new device can run on any sort of organic material—not only wastewater, but also straw, animal waste and byproducts from the industrial production of beer and dairy.

The researchers say they have proven the technology at a fairly substantial scale in the lab, and are ready to proceed to a large-scale pilot study. They are seeking funding to set up a large-scale fuel cell, ideally coupled with a food processing plant, which would produce a consistent and high-volume flow of wastewater. They predict that, once the technology is proven and the construction costs come down, the application of this sort of wastewater processing will produce low-cost renewable electricity and reduce the cost of processing sewage.

This technology would be especially appealing in a developing country, where it would immediately solve two problems: a lack of cheap electricity and a scarcity of clean water. Research into improving the efficiency of the process is still ongoing, but it seems that soon enough, the days of flushing energy down the toilet will be over.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)